NASA’s Dawn spacecraft has been poking around Ceres since it first established orbit in March of 2015. In that time, the mission has sent back a steam of images of the minor planet, and with a level of resolution that was previously impossible. Because of this, a lot of interesting revelations have been made about Ceres’ composition and surface features (like its many “bright spots“).

In what is sure to be the most surprising find yet, the Dawn spacecraft has revealed that Ceres may actually possess the ingredients for life. Using data from the Dawn spacecraft’s Visible and InfraRed Mapping Spectrometer (VIMS), an international team of scientists has confirmed the existence of organic molecules on Ceres – a find which could indicate that it has conditions favorable to life.

These findings – which were detailed in a study titled “Localized aliphatic organic material on the surface of Ceres” – appeared in the Feb. 17th, 2017, issue of Science. For the sake of their study, the international team of researchers – which was led by Maria Cristina de Sanctis from the National Institute of Astrophysics in Rome, Italy – showed how Dawn sensor data pointed towards the presence of aliphatic compounds on the surface.

Aliphatics are a type of organic compound where carbon atoms form open chains that are commonly bound with oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur and chlorine. The least complex aliphatic is methane, which has been detected in many locations across the Solar System – including in the Martian atmosphere and in both liquid and gaseous form on Saturn’s moon Titan.

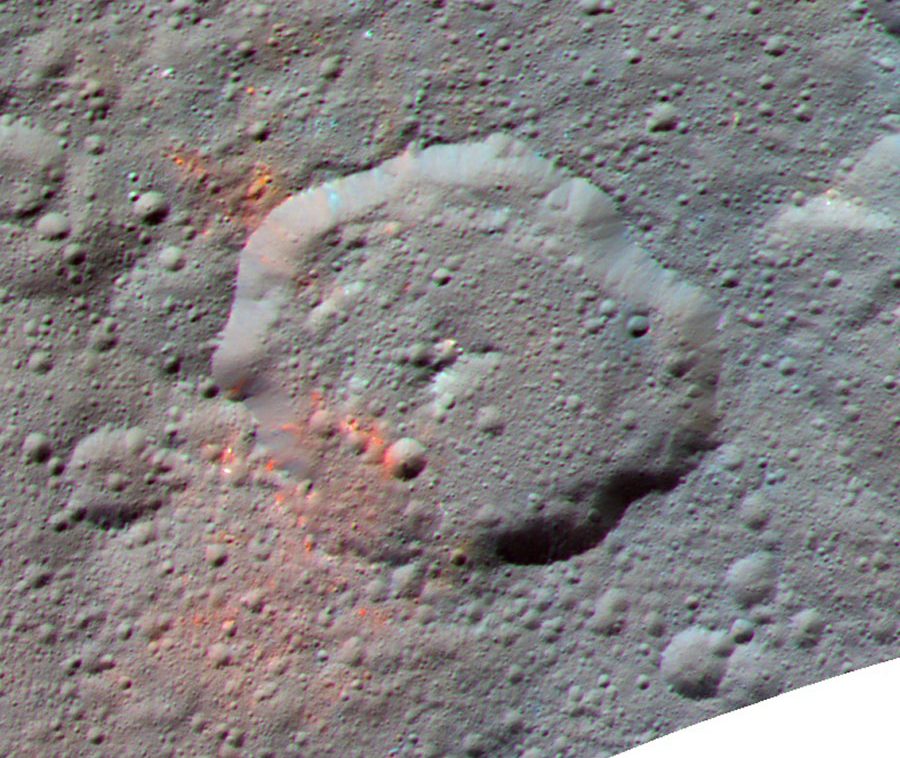

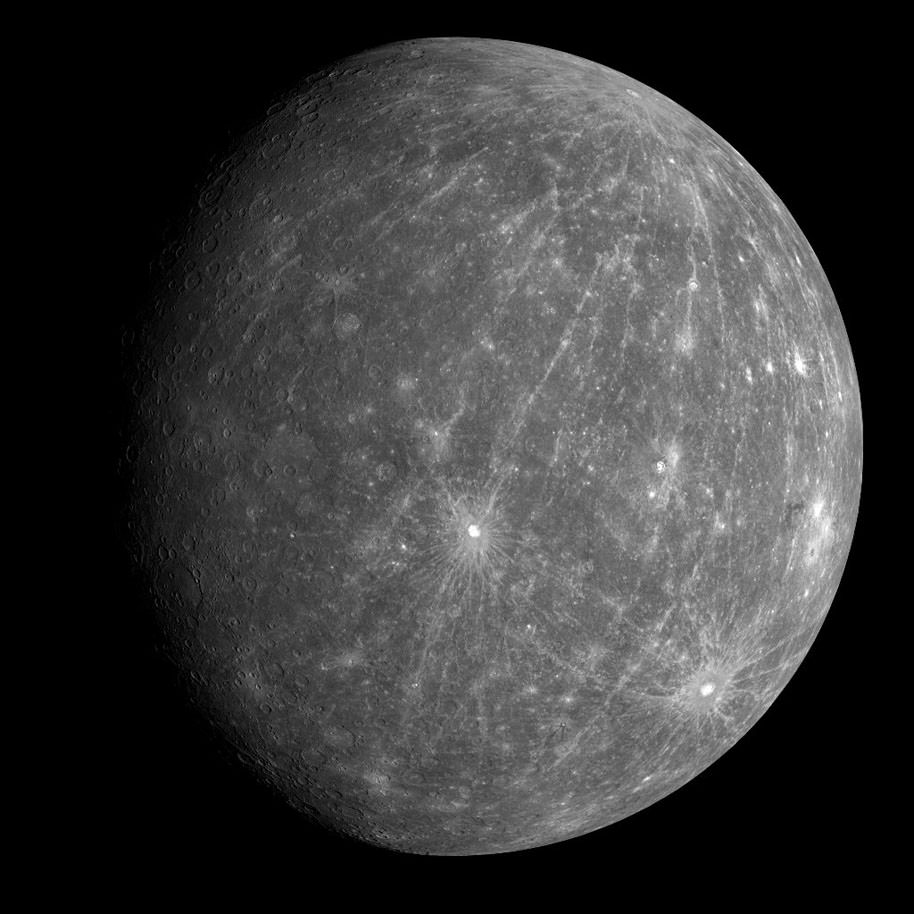

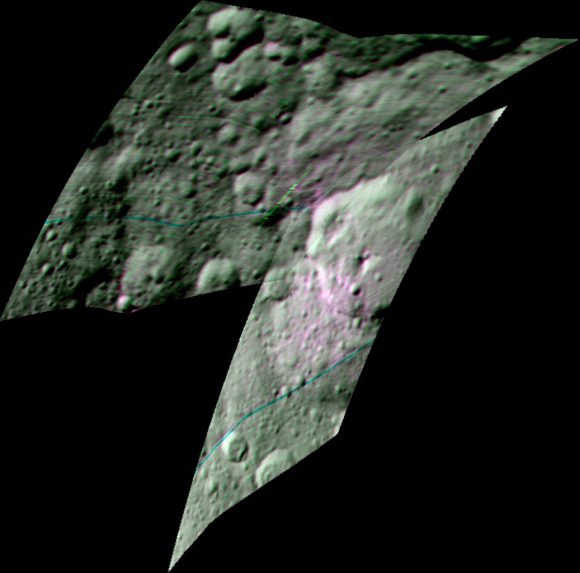

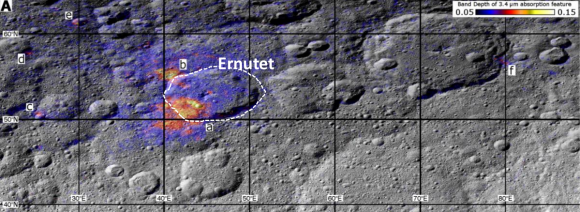

From their study, Dr. de Sanctis and her colleagues determined that spectral data obtained by the VIMS instrument corresponded to the presence of these hydrocarbons in a region outside of the Ernutet crater. This crater, which is located in the northern hemisphere of Ceres, measures about 52 km (32 mi) in diameter. The aliphatic compounds which were detected were localized in a roughly 1000 square kilometers region around it.

The team ruled out the possibility that these organic molecules were deposited from an external source – such as a comet or carbonaceous chondrite asteroid. While both have been shown to contain organic molecules in their interior in the past, the largest concentrations on Ceres were distributed discontinuously across the southwest floor and rim of the Ernutet crater and onto an older, highly degraded crater.

In addition, other organic-rich areas were spotted being are scattered to the northwest of the crater. As Dr. Maria Cristina De Sanctis told Universe Today via email:

“The composition that we see on Ceres is similar to some meteorites that has organics and thus we searched for this material. We considered both endogenous and exogenous origin, but the last one seems less likely due to several reasons including the larger abundance observed on Ceres with respect the meteorites.”

Instead, they considered the possibility that they organic molecules were endogenous in origin. In the past, surveys have shown evidence of hydrothermal activity on Ceres, which included signs of surface renewal and fluid mobility. Combined with other surveys that have detected ammonia-bearing hydrated minerals, water ice, carbonates, and salts, this all points towards Ceres having an environment that can support prebiotic chemistry.

“The overall composition of Ceres can favor the pre-biotic chemistry,” said De Sanctis. “Ceres has water ice and minerals (carbonates and phyllosilicates) derived from pervasive aqueous alteration of rocks. It has also material that we think is formed in hydrothermal environments. All these information indicate condition not hostel to biotic molecules.”

These findings are certainly significant in helping to determine if life could exist on Ceres – in a way that is similar to Europa and Enceladus, locked away beneath its icy mantle. But given that Ceres is believed to have originated 4.5 billion years ago (when the Solar System was still in the process of formation), this study is also significant in that it can shed light on the origin, evolution, and distribution of organic life in our the Solar System.

Other members of the research team include researchers from the department of Earth Planetary and Space Sciences at the University of California, the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at the University of Tennessee, the Department of Earth, Environmental, and Planetary Sciences at Brown University, the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center, and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

Further Reading: ScienceMag, SwRI