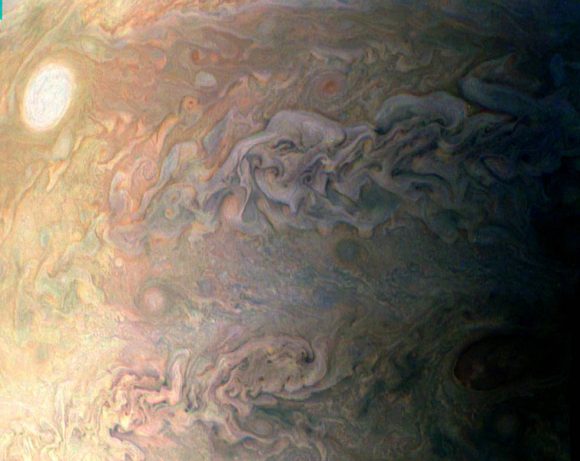

In the movie 2010: The Year We Make Contact, the sequel to Stanley’s Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, black Monoliths multiply, converge and transform Jupiter into a new star. We next hear astronaut David Bowman’s disembodied voice with this message: “All these worlds are yours except Europa. Attempt no landing there.” The newborn sun warms Europa, transforming the icy landscape into a primeval jungle. At the end, a single Monolith appears in the swamp, waiting once again to direct the evolution of intelligent life forms.

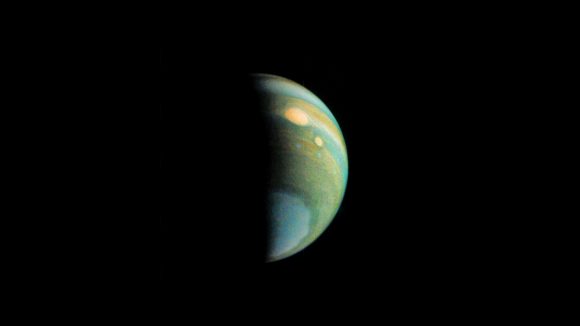

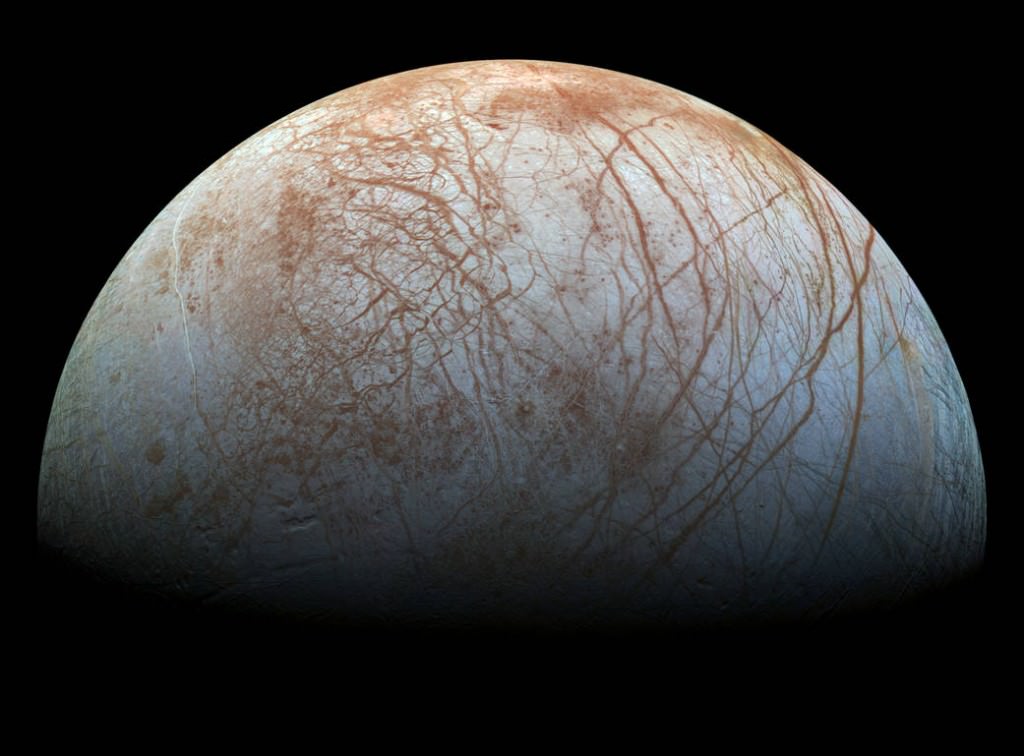

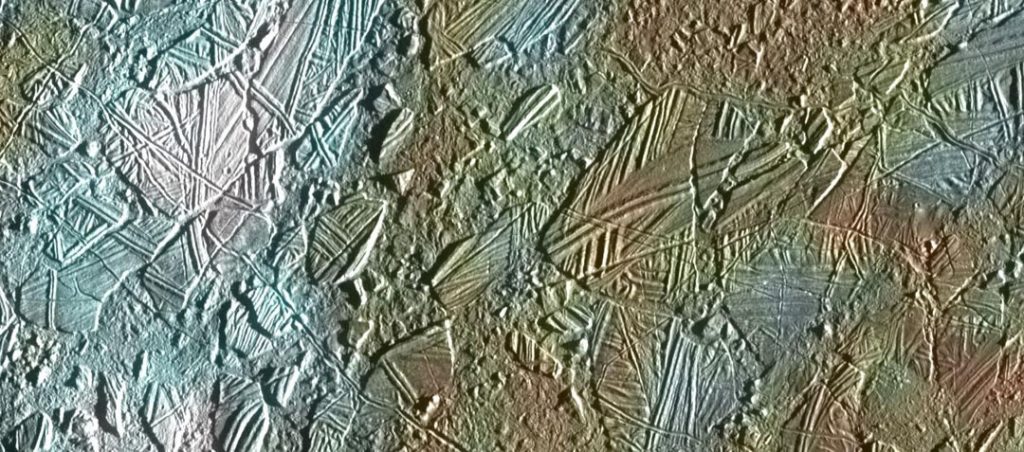

Stay away from Europa? No way. It’s just too fascinating a place with its jigsaw-puzzle ice sheets, crisscross valleys, miles of ice on top and a warm, salty ocean below. The movie was prescient — if you’re going to search for life elsewhere in the solar system, Europa’s one of the best candidates.

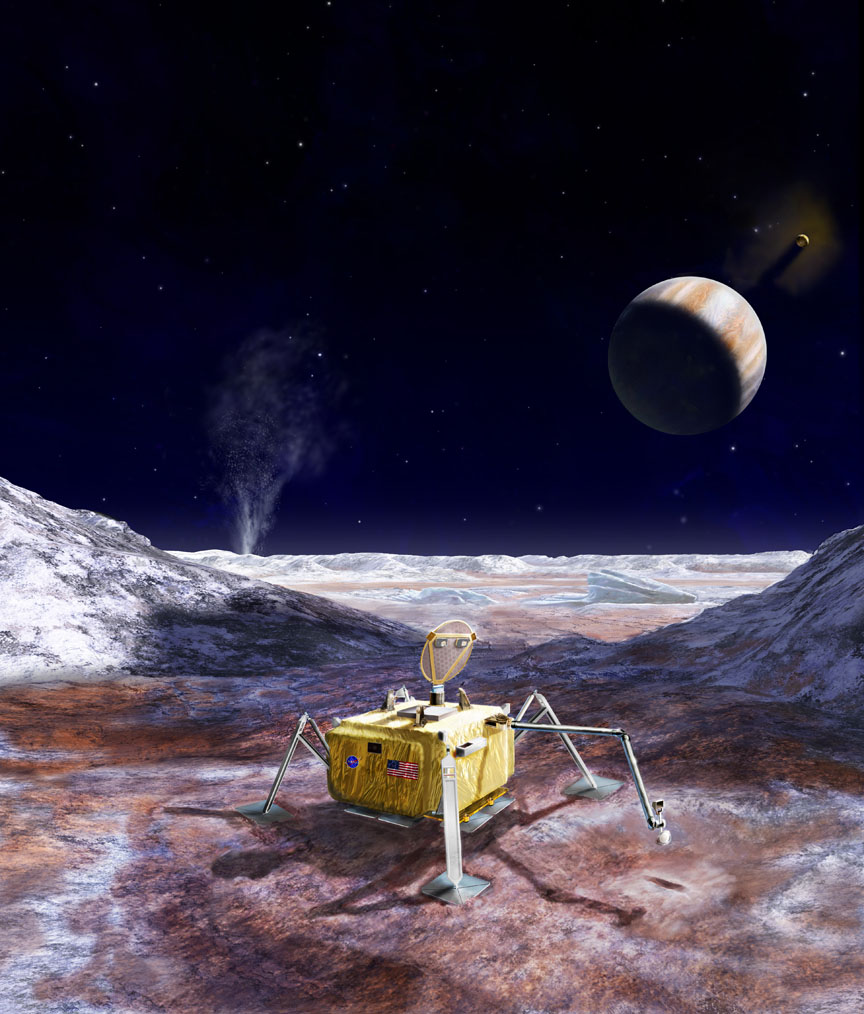

While we’ve sent spacecraft to photograph and study the icy moon during orbital flybys, no lander has yet to touch the surface. That may change soon. In early 2016, in response to a congressional directive, NASA’s Planetary Science Division began a pre-Phase A study to assess the science value and engineering design of a future Europa lander mission. In June 2016, NASA convened a 21-member team of scientists for the Science Definition Team (SDT). The team put together set of science objectives and measurements for the mission concept and submitted the report to NASA on Feb. 7.

The report lists three science goals for the mission. The primary goal is to search for evidence of life on Europa. The other goals are to determine the habitability of Europa by directly analyzing material from the surface, and to characterize the surface and subsurface to support future robotic exploration of Europa and its ocean.

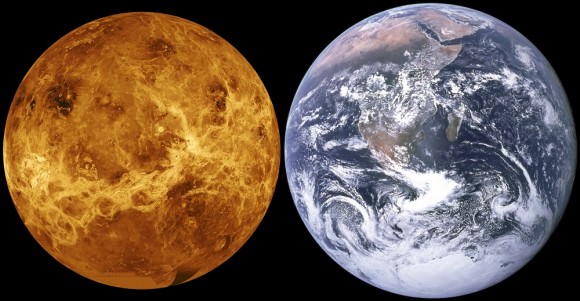

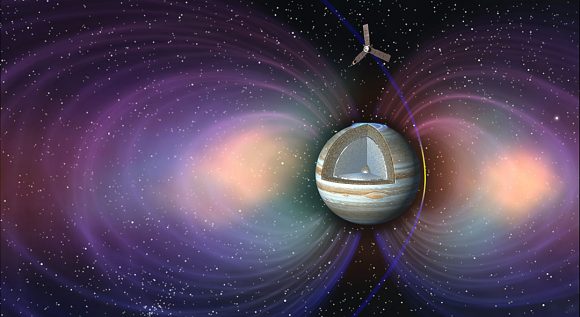

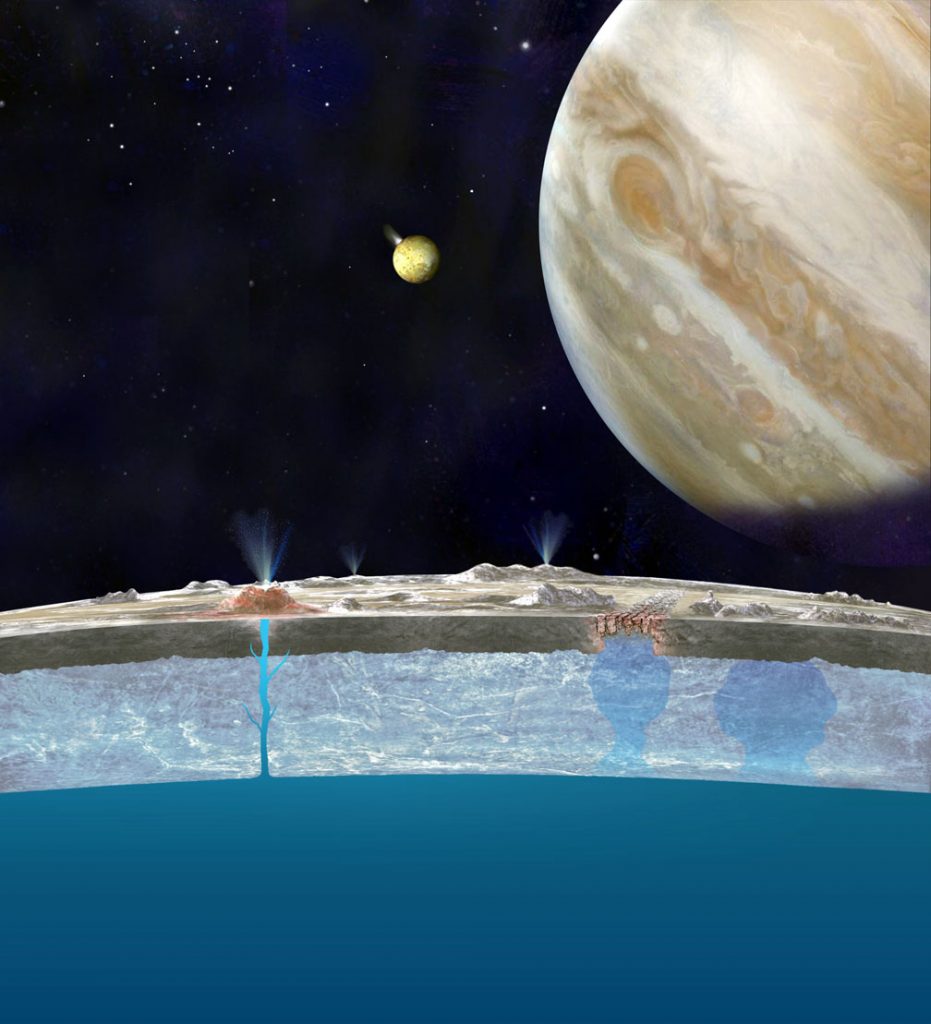

The evidence is quite strong that Europa, with a diameter of 1,945 miles — slightly smaller than Earth’s moon — has a global saltwater ocean beneath its icy crust. This ocean has at least twice as much water as Earth’s oceans. Two things make Europa’s ocean unique and give the moon a greater chance of supporting microbial life compared to say, Ganymede and Enceladus, which also hold water reservoirs beneath their crusts.

One: the ocean is relatively close to the surface, just 10-15 miles below the moon’s icy shell. Radiation from Jupiter (high-speed electrons and protons) bombards ice, sulfur and salts on the surface to create compounds that could trickle down into warmer regions and used by living things for growth and metabolism.

Two: While recent discoveries have shown that many bodies in the solar system either have subsurface oceans now, or may have in the past, Europa is one of only two places where the ocean appears to be in contact with a rocky seafloor (the other being Saturn’s moon Enceladus). This rare circumstance makes Europa one of the highest priority targets in the search for present-day life beyond Earth.

On Earth, chemical interactions between life and lifeless rock in deep oceans and within the outer crust provide the energy needed to power and sustain microbial life. For all we know, deep sea volcanoes belch essential elements into the salty waters spawned by the constant flexing and heating of the moon as it orbits Jupiter every 85 hours.

The SDT was tasked with developing a life-detection strategy, a first for a NASA mission since the Mars Viking mission era more than four decades ago. The report makes recommendations on the number and type of science instruments that would be required to confirm if signs of life are present in samples collected from the icy moon’s surface.

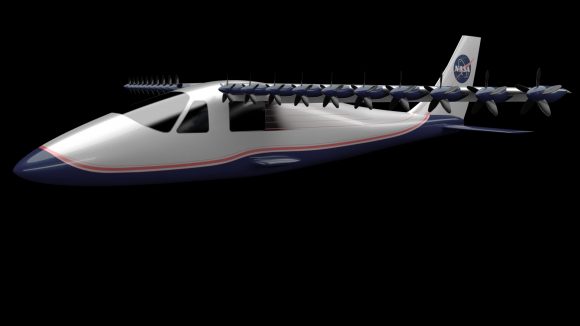

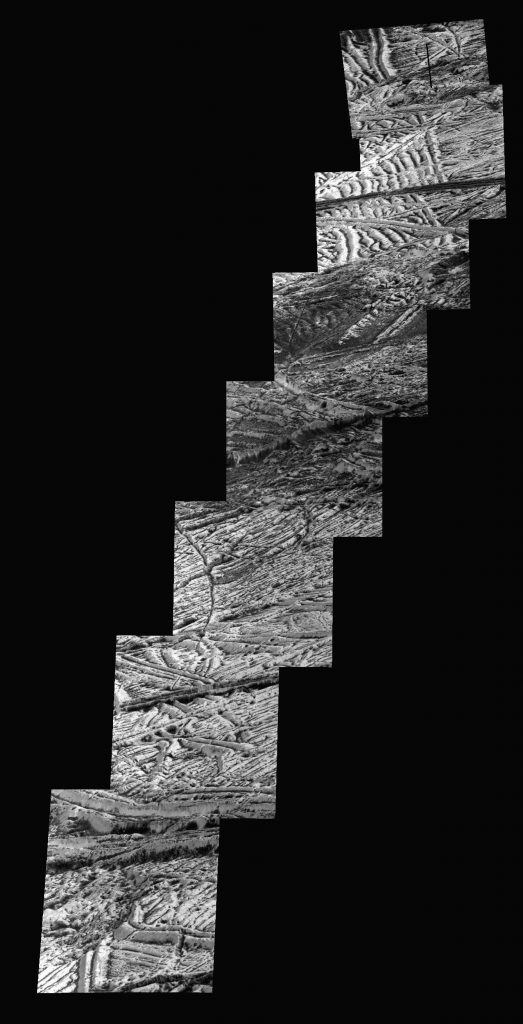

The team also worked closely with engineers to design a system capable of landing on a surface about which very little is known. Given that Europa has no atmosphere, the team developed a concept that could deliver its science payload to the icy surface without the benefit of technologies like a heat shield or parachutes.

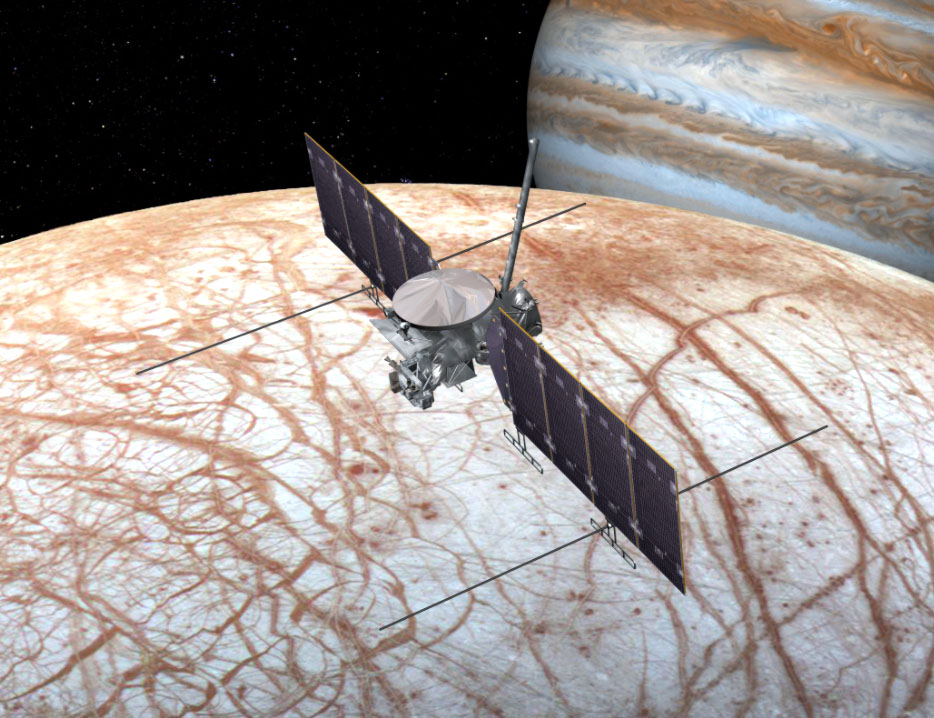

The concept lander is separate from the solar-powered Europa multiple flyby mission, now in development for launch in the early 2020s. The spacecraft will arrive at Jupiter after a multi-year journey, orbiting the gas giant every two weeks for a series of 45 close flybys of Europa. The multiple flyby mission will investigate Europa’s habitability by mapping its composition, determining the characteristics of the ocean and ice shell, and increasing our understanding of its geology. The mission also will lay the foundation for a future landing by performing detailed reconnaissance using its powerful cameras.

We can’t help but be excited by the prospects of life-seeking missions to Europa. Sometimes wonderful things come in small packages.