Perhaps you’ve seen them while driving through the countryside. Or maybe you saw them just off the coast, looming large on the horizon with their spinning blades. Then again, you may have seen them on someone’s roof, or as part of a small-scale urban operation. Regardless of the location, wind turbines and wind power are becoming an increasingly common feature in the modern world.

Much of this has to do with the threat of Climate Change, air pollution, and the desire to wean humanity off its dependence on fossil fuels. And when it comes to alternative and renewable energy, wind power is expected to occupy the second-largest share of the market in the future (after solar). But just how exactly do wind turbines work?

Description:

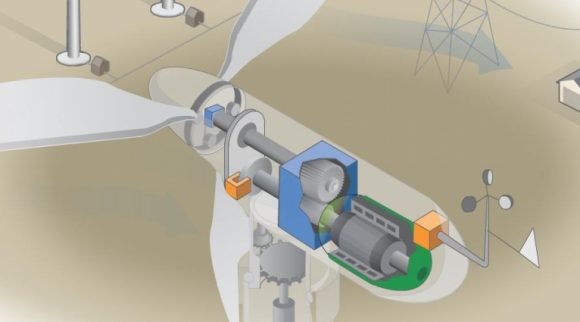

Air turbines are devices that turn the kinetic energy of wind and changes in air flow into electrical energy. In general, they consist of the following components: a rotor, a generator, and a structural support component (which can take the form of either a tower, a rotor yaw mechanism, or both).

A rotor consists of the blades that capture the wind’s energy and a shaft, which converts the wind energy to low-speed rotational energy. The generator – which is connected to the shaft – converts the slow rotation to high into electrical energy using a series of magnets and a conductor (which usually consists of coiled copper wire).

When the magnets rotate around with the copper wire, its produces a difference in electrical potential, creating voltage and an electric current. Lastly, there is the structural support component, which ensures that the turbine either stands at a high enough altitudes to optimally capture changes in wind pressure, and/or face in the direction of wind flow.

Types of Wind Turbines:

At present, there are two main types of wind turbines – Horizontal Axis Wind Turbines (HAWT) and Vertical Axis Wind Turbines (VAWT). As the name would imply, horizontal wind turbines have a main rotor shaft and electrical generator at the top of a tower, with the blades pointed into the wind. The turbine is usually positioned upwind of its supporting tower, since the tower is likely to produce turbulence behind it.

Vertical axis turbines (once again, as the name implies) have the main rotor shaft arranged vertically. Typically, these are smaller in nature, and do not need to be pointed in the direction of the wind in order to rotate. They are thereby being able to take advantage of wind that is variable in terms of direction.

In general, horizontal axis wind turbines are considered more efficient and can produce more power. While the vertical model generates less electricity it can be placed at lower elevations and needs less in the way of components (particularly a yaw mechanism). Wind turbines can also be divided into three general groups based on their design, which includes the Towered, Savonius, and Darrieus models.

The towered model is the most conventional form of HAWT, consisting of a tower (as the name would suggest) and a series of long blades that sit ahead of (and parallel to) the tower. The Savonis is a VAWT model that relies on contoured blades (scoops) to capture wind and spin. They are generally low-efficiency, but have the benefit of being self-starting. These sorts of turbines are often part of rooftop wind operations or mounted on sea vessels.

The Darrieus model, also known as an “Eggbeater” turbine, is named after the French inventor who pioneered the design – Georges Darrieus. This VAWT model employs a series of vertical blades that sit parallel to the vertical support. They are generally low efficiency, require an additional rotor to start turning, produce high-torque, and place high stress on the tower. Hence, they are considered unreliable as designs go.

History of Development:

Wind power has been used for thousands of years to push sails, power windmills, or to generate pressure for water pumps. The earliest known examples come from Central Asia, where windmills used in ancient Persia (Iran) have been dated to between 500 – 900 CE. The technology began to appear in Europe during the Middle Ages, and became a common feature by the 16th century.

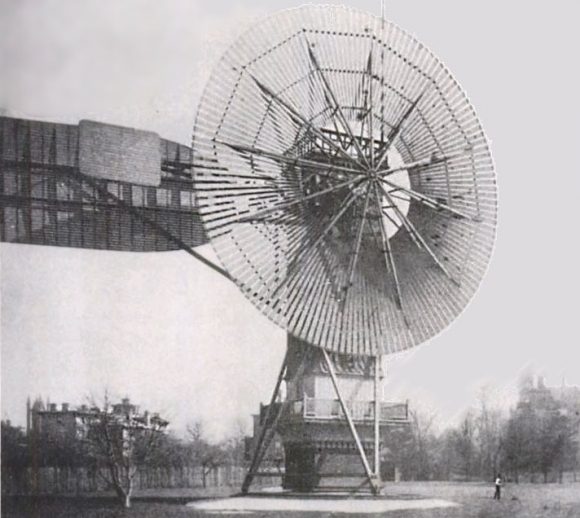

By the 19th century, with the development of electrical power, the first wind turbines capable of generating electricity were built. The first was installed in 1887 by Scottish academic James Blyth to light his holiday home in Marykirk, Scotland. In 1888, American inventor Charles F. Brush built the first automated wind turbine to power his home in Cleveland, Ohio.

By the early 20th century, wind turbines began to become a common means of powering homes in remote areas (such as farmsteads). In 1941, the first megawatt-class wind turbine was installed in Vermont and attached to the local utility grid. In 1951, the UK installed its first utility-grid connected wind turbine in the Orkney Islands.

By the 1970s, research and development into wind turbine technology advanced considerably thanks to the OPEC crisis and protests against nuclear power. In the ensuing decades, associations and lobbyists dedicated to alternative energy began to emerge in western European nations and the United States. By the final decade of the 20th century, similar efforts emerged in India and China due to growing air pollution and rising demand for clean energy.

Wind Power:

Compared to other forms of renewable energy, wind power is considered very reliable and steady, as wind is consistent from year to year and does not diminish during peak hours of demand. Initially, the construction of wind farms was a costly venture. But thanks to recent improvements, wind power has begun to set peak prices in wholesale energy markets worldwide and cut into the revenues and profits of the fossil fuel industry.

According to a report issued by the Department of Energy in March of 2015, the growth of wind power in the United States could lead to even more highly skilled jobs in many categories. Titled “Wind Vision: A New Era for Wind Power in the United States”, the document indicates that by 2050, the industry could account for as much as 35% of the US’ electrical production.

In addition, in 2014, the Global Wind Energy Council and Greenpeace International came together to publish a report titled “Global Wind Energy Outlook 2014”. This report stated that worldwide, wind power could provide as much as 25 to 30% of global electricity by 2050. At the time of the report’s writing, commercial installations in more than 90 countries had a total capacity of 318 gigawatts (GW), providing about 3.1% of global supply.

This represents a nearly sixteen-fold increase in the rate of adoption since the year 2000, when wind power accounted for less than 0.2%. Another way to look at it would be to say that the market share of wind power has doubled four times in less than 15 years. This places it second only to solar power, which doubled seven times over in the same period, but still trails wind in terms of its overall market share (at about 1% by 2014).

In terms of its disadvantages, one consistently raised issue is the effect wind turbines have on local wildlife, and the disturbance their presence has on the local landscape. However, these concerns have often been shown to be inflated by special interest groups and lobbyists seeking to discredit wind power and other renewable energy sources.

For instance, a 2009 study released by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory determined that less than 1 acre per megawatt is disturbed permanently by the construction of large-scale wind farms, and less than 3.5 acres per megawatt are disturbed temporarily. The same study concluded that the impacts are relatively low on bird and bat wildlife, and that the same conclusions hold true for offshore platforms.

All over the world, governments and local communities are looking to wind power in order to meet their energy needs. In an age of rising fuel prices, growing concerns over Climate Change, and improving technology, this is hardly surprising. At its current rate of adoption, it is likely to be one of the largest sources of energy by mid-century.

And be sure to enjoy this video about wind turbines, courtesy of NASA’s Lewis Research Center:

We have written many interesting articles on wind turbines and wind power here at Universe Today. Here’s What is Alternative Energy?, What are Fossil Fuels?, What are the Different Types of Renewable Energy?, Wind Power on the Ocean (with Help from Space), and Could the World Run on Solar and Wind Power?

For more information, check out How Stuff Works’s article about the history and mechanics of wind power and NASA’s Greenspace page.

Astronomy Cast also has some episodes that are relevant to the subject. Here’s Episode 51: Earth and Episode 308: Climate Change.

Sources: