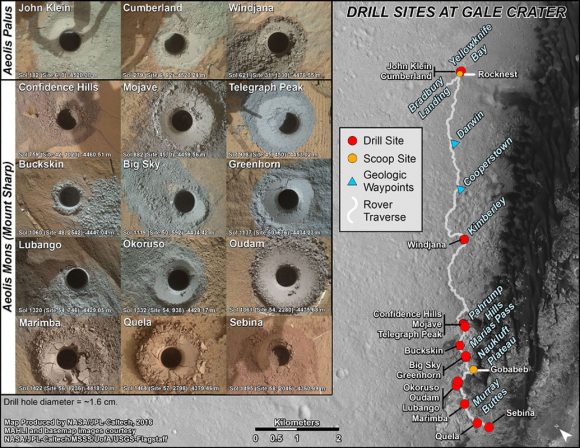

For over a year, the Curiosity rover has been making its way up the slopes of Mount Sharp, the central peak within the Gale Crater. As the rover moves higher along this formation, it has been taking drill samples so that it might look into Mars’ ancient past. Combined with existing evidence that water existed within the crater, this would have provided favorable conditions for microbial life.

And according to the most recent findings announced by the Curiosity science team, the upper levels of the mountain are rich in minerals that are not found at the lower levels. These findings reveal much about how the Martian environment has changed over the past few billion years, and are further evidence that Mars may have once been habitable.

The findings were presented at the Fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU), which began on Monday, Dec. 12th, in San Fransisco. During the meeting, John Grotzinger – the Fletcher Jones Professor of Geology at Caltech and the former Project Scientist for the Curiosity mission – and other members of Curiosity’s science team shared what the rover discovered while digging into mineral veins located in the higher, younger layers of Mount Sharp.

To put it simply, mineral veins are a great way to study the movements of water in an area. This is due to the fact that veins are the result of cracks in layered rock being filled with chemicals that are dissolved in water – a process which alters the chemistry and composition of rock formations. What the rover found was that at higher layers hematite, clay minerals and boron are more abundant than what has been observed at lower, older layers.

These latest findings paint a complex picture of the region, where groundwater interactions led to clay-bearing sediments and diverse minerals being deposited over time. As Grotzinger explained, this kind of situation is favorable as far as habitability is concerned:

“There is so much variability in the composition at different elevations, we’ve hit a jackpot. A sedimentary basin such as this is a chemical reactor. Elements get rearranged. New minerals form and old ones dissolve. Electrons get redistributed. On Earth, these reactions support life.”

At present, no evidence has been found that microbial life actually existed on Mars in the past. However, since it first landed back in 2012, the Curiosity mission has uncovered ample evidence that conditions favorable to life existed billions of years ago. This is possible thanks to the fact that Mount Sharp consists of layered sedimentary deposits, where each one is younger than the one beneath it.

These sedimentary layers act as a sort of geological and environmental record for Mars; and by digging into them, scientists are able to get an idea of what Mars’ early history looked like. In the past, Curiosity spent many years digging around in the lower layers, where it found evidence of liquid water and all the key chemical ingredients and energy needed for life.

Since that time, Curiosity has climbed higher along Mount Sharp and examined younger layers, the purpose of which has been to reconstruct how the Martian environment changed over time. As noted, the samples Curiosity recently obtained showed greater amounts of hematite, clay minerals and boron. All of these provide very interesting clues as to what kinds of changes took place.

For instance, compared to previous samples, hematite was the most dominant iron oxide mineral detected, compared to magnetite (which is a less-oxidized form of iron oxide). The presence of hematite, which increases with distance up the slope of Mount Sharp, suggests both warmer conditions and more interaction with the atmosphere at higher levels.

The increasing concentration of this minerals – relative to magnetite at lower levels – also indicates that environmental changes have occurred where the oxidation of iron increased over time. This process, in which more electrons are lost via chemical exchanges, can provide the energy necessary for life.

In addition, Curiosity’s Chemistry and Camera (ChemCam) instrument has also noted increased (but still minute)) levels of borons within veins composed primarily of calcium sufate. On Earth, boron is associated with arid sites where water has evaporated, and its presence on Mars was certainly unexpected. No previous missions have ever detected it, and the environmental implications of it being present in such tiny amounts are unclear.

On the one hand, it is possible that evaporation within the lake bed created a boron-deposit deeper inside Mount Sharp. The movement of groundwater within could have then dissolved some of this, redepositing trace amounts at shallower levels where Curiosity was able to reach it. On the other hand, it could be that changes in the chemistry of clay-bearing deposits affected how boron was absorbed by groundwater and then redeposited.

Either way, the differences in terms of the composition of upper and lower levels in the Gale Crater creates a very interesting picture of how the local environment changed over time:

“Variations in these minerals and elements indicate a dynamic system. They interact with groundwater as well as surface water. The water influences the chemistry of the clays, but the composition of the water also changes. We are seeing chemical complexity indicating a long, interactive history with the water. The more complicated the chemistry is, the better it is for habitability. The boron, hematite and clay minerals underline the mobility of elements and electrons, and that is good for life.”

It seems that with every discovery, the long history of “Earth’s Twin” is becoming more accessible, yet more mysterious. The more we learn about it past and how it came to be the cold, desiccated place we know today, the more we want to know!

Further Reading: NASA