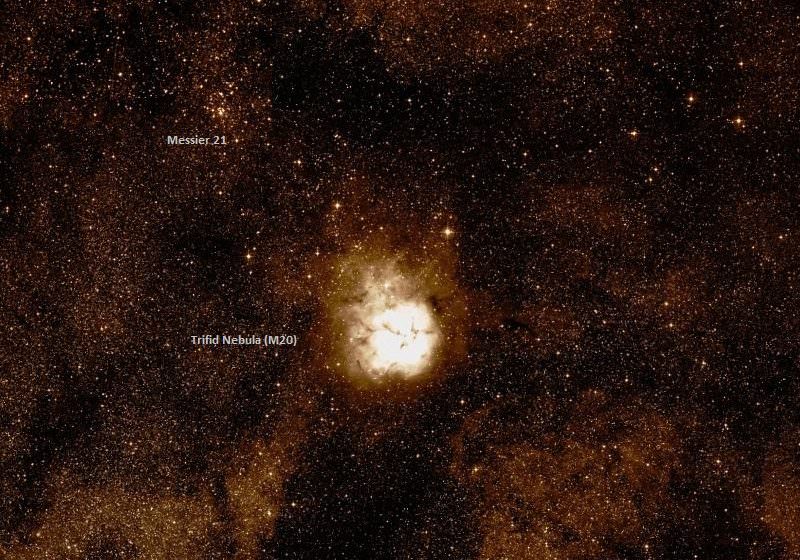

Welcome back to Messier Monday! In our ongoing tribute to the great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at the Sagittarius Cluster (aka. Messier 22). Enjoy!

Back in the 18th century, famed French astronomer Charles Messier noted the presence of several “nebulous objects” in the night sky. Having originally mistaken them for comets, he began compiling a list of these objects so that others wouldn’t make the same mistake. Consisting of 100 objects, this “Messier Catalog” would come to be viewed by posterity as a major milestone in the study of Deep Space Objects.

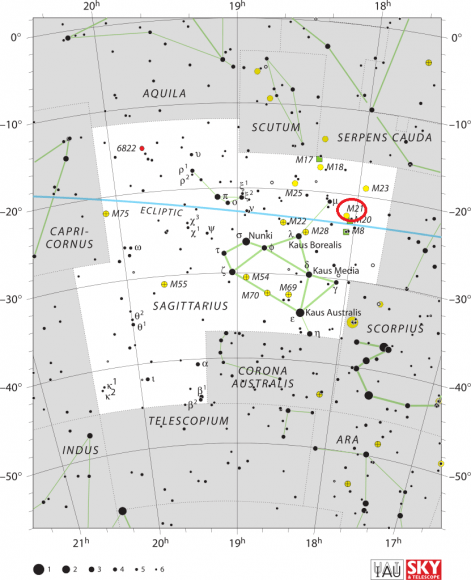

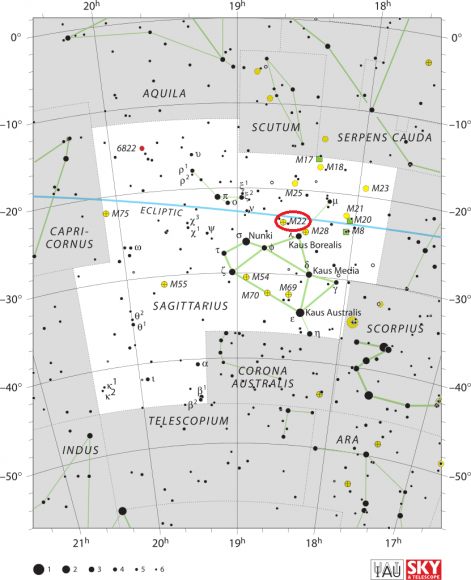

One of these objects is the Sagittarius Cluster, otherwise known as Messier 22 (and NGC 6656). This elliptical globular cluster, is located in the constellation Sagittarius, near the Galactic bulge region. It is one of the brightest globulars visible in the night sky, and was therefore one of the first of its kind to be discovered and later studied.

Description:

Located around 10,400 light years from our Solar System, in the direction of Sagittarius, M22 occupied a volume of space that is 200 light years in diameter and is receding away from us at 149 kilometers per second. M22 has a lot in common with many other clusters of its type, which includes being a gravitationally bound sphere of stars, and that most of its stars are all about the same age – about 12 billion years old.

It is part of our galactic halo, and may once have been part of a galaxy that our Milky Way cannibalized. But it’s there that the similarities end. For example, it consists of at least 70,000 individual stars, only 32 of which are variable stars. It also spans an incredible 32 arc minutes in the sky and ranks as the fourth brightness of all the known globular clusters in our galaxy.

And four must be its lucky number, because it is also one of only four globular clusters known to contain a planetary nebula. Recent Hubble Space Telescope investigations of Messier 22 have led to the discovery of an astonishing discovery. For starters, in 1999, astronomers discovered six planet-sized objects floating around inside the cluster that were about 80 times the mass of Earth!

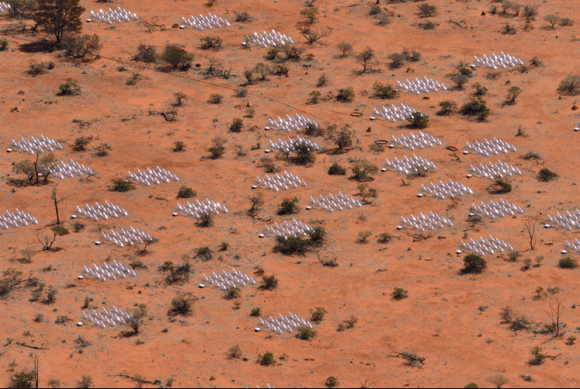

Using a technique known as microlensing, which measures the way gravity bends the light of the background stars, the Hubble Space Telescope was able to determine the existence of the gas giant. Even though the Hubble can’t resolve them because the angle at which the light bends is about 100 times smaller than the telescope’s angular resolution, scientist know they are there because the gravity “powers up” the starlight, making it brighter each time a body passes in front of it.

Because a microlensing event is very rare and totally unpredictable, the Hubble team needed to monitor 83,000 stars every three days for nearly four months. Luckily, a sharp peak in brightness was all the proof they needed that they were on the right track.

Said Kailash Sahu, of the Space Telescope Science Institute, Baltimore, MD, of the discovery in 2007: “Hubble’s excellent sharpness allowed us to make this remarkable new type of observation, successfully demonstrating our ability to see very small objects. This holds tremendous potential for further searches for dark, low-mass objects.”

During their study time, the Hubble team caught six microlensing events that lasted less than 20 hours and one which endured for 18 days. By calculating the times of the eclipses and the spikes in brightness, astronomers could then estimate the mass of the object passing in front of the star. These wandering rogues might be planets torn away from their parent stars by the huge amounts of gravitational influence from so many closely packed suns – or (in the case of the long event) simply a smaller mass star passing in front of another.

They could be brown dwarfs, or even a totally new type of object. As co-investigator Nino Panagia of the European Space Agency and Space Telescope Science Institute said: “Since we know that globular clusters like M22 are very old, this result opens new and exciting opportunities for the discovery and study of planet-like objects that formed in the early universe,”

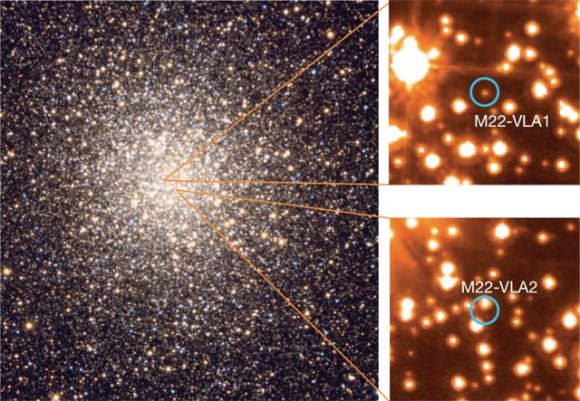

Two black holes were also discovered in M22 and confirmed by the Chandra X-ray telescope in 2012. The objects have between 10 and 20 solar masses, and their discovery suggests that there may be 5 to 100 black holes within the cluster (and maybe some multiple black holes as well). The presence of black holes and their interaction with the stars of M22 could explain the cluster’s unusually large central region.

Other objects of interesting include two black holes – M22-VLA1 and M22-VLA2 – both of which are part of binary star systems. Each has a companion star and is pulling matter from it. This gas and dust, in turn, forms an accretion disk around each black hole, creating emissions that scientists used to confirm their existence.

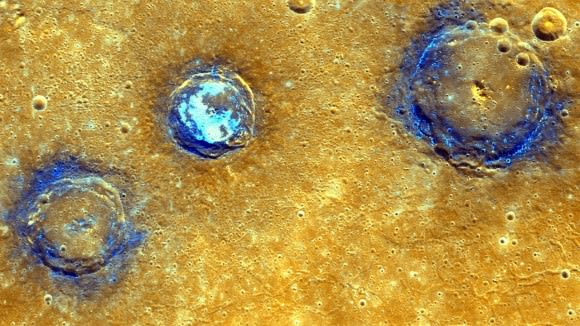

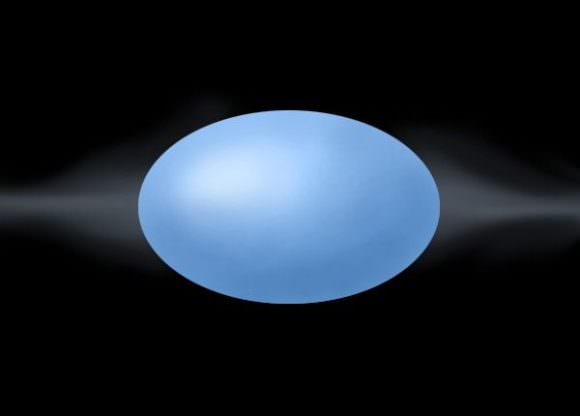

Messier 22 is one of only four known globular clusters that contain a planetary nebula. This nebula – catalogued as GJJC1 or IRAS 18333-2357 – is rather small and young, being only 3 arcseconds in diameter and 6,000 years old. It was discovered in 1986 using the infrared satellite IRAS, and identified as a planetary nebula in 1989.

History of Observation:

Chances are, magnificent Messier 22 was probably the first globular cluster to ever be recorded in the history of astronomy, most likely by Abraham Ihle in 1665. Over the years it has been included in many historic observations, including Edmund Halley’s list of 6 objects published 1715, and observed by De Chéseaux (his Number 17) and Le Gentil, as well as by Abbe Nicholas Louis de la Caille, who included it in his catalog of southern objects (as Lacaille I.12).

However, it was Charles Messier who made it famous when he cataloged it as M22 on June 5th, 1764. As he said of the object at the time:

“I have observed a nebula situated a bit below the ecliptic, between the head and the bow of Sagittarius, near the star of seventh magnitude, the twenty-fifth of that constellation, according to the catalog of Flamsteed. That nebula didn’t appear to me to contain any star, although I have examined it with a good Gregorian telescope which magnified 104 times: it is round, and one sees it very well with an ordinary refractor of 3 feet and a half; its diameter is about 6 minutes of arc. I have determined its position by comparing with the star Lambda Sagittarii: its right ascension has been concluded as 275d 28′ 39″, and its declination as 24d 6′ 11”. It was Abraham Ihle, a German, who discovered this nebula in 1665, when observing Saturn. M. le Gentil has examined it also, and he has made an engraving of the configuration in the volume of the Memoirs of the Academy, for the year 1759, page 470. He observed it on August 29, 1747, under good weather, with a refractor of 18 feet length: He also observed it on July 17, and on other days. “It always appeared to me,” he says, “very irregular in its figure, hair and distributing in space of rays of light all over its diameter.”

While Messier’s description is a wonder, let us remember that he was a comet hunter by profession. Once more, it was the observer Admiral Smythto whom we are indebted for the most detailed and vivid description of the cluster:

“A fine globular cluster, outlying that astral stream, the Via Lactea [Milky Way], in the space between the Archer’s head and bow, not far from the point of the winter solstice, and midway between Mu and Sigma Sagittarii. It consists of very minute and thickly condensed particles of light, with a group of small stars preceding by 3m, somewhat in a crucial form. Halley ascribes the discovery of this in 1665, to Abraham Ihle, the German; but it has been thought this name should have been Abraham Hill, who was one of the first council of the Royal Society, and was wont to dabble with astronomy. Hevelius, however, appears to have noticed it previous to 1665, so that neither Ihle nor Hill can be supported.

“In August, 1747, it was carefully drawn by Le Gentil, as seen with an 18-foot telescope, which drawing appears in the Mémoires de l’Académie for 1759. In this figure three stars accompany the cluster, and he remarks that two years afterwards he did not see the preceding and central one: I, however, saw it very plainly in 1835. In the description he says, “Elle m’a toujours parue tres-irrégulière dans sa figure, chevelue, et rependant des espèces de rayons de lumière tout autout de son diamètre.” This passage, I quote, “as in duty bound;” but from familiarity with the object itself, I cannot say that I clearly understand how or why his telescope exhibited these “espèces de rayons.” Messier, who registered it in 1764, says nothing about them, merely observing that it is a nebula without a star, of a round form; and Sir William Herschel, who first resolved it, merely describes it as a circular cluster, with an estimated profundity of the 344th order. Sir John Herschel recommends it as a capital test for trying the space-penetrating power of a telescope.

“This object is a fine specimen of the compression on which the nebula-theory is built. The globular systems of stars appear thicker in the middle than they would do if these stars were all at equal distances from each other; they must, therefore, be condensed toward the centre. That the stars should be accidentally disposed is too improbable a supposition to be admitted; whence Sir William Herschel supposes that they are thus brought together by their mutual attractions, and that the gradual condensation towards the centre must be received as proof of a central power of such kind.”

Locating Messier 22:

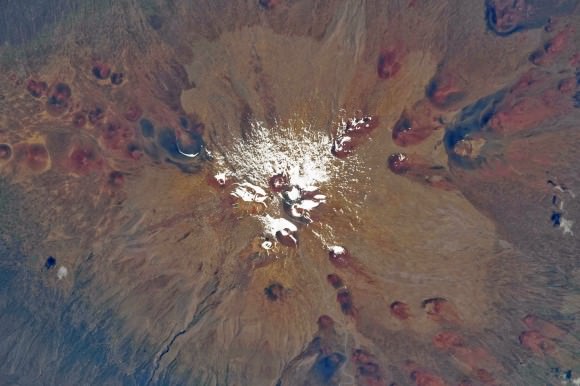

From its position almost on the ecliptic plane, bright globular cluster M22 is easy to find in optics of all sizes. The most important clue is simply identifying the Sagittarius “teapot” shape. Once you’ve located it, just choose the “lid” star, Lambda (Kaus Borealis) and look about a fingerwidth (2 degrees) due northeast. In binoculars, if you center on Lambda, M22 will appear in the 10:00 region of your field of view.

In a finderscope, you will need to hop from Lambda northeast to 24 Sagittari and you’ll see it as a faint fuzzy nearby also to the northeast. From a dark sky location, Messier Object 22 can also sometimes be spotted with the unaided eye! No matter what size optics you use, this large, very luminous ball of stars is quite appealing. A joy to binocular users and an exercise in resolution to telescopes.

And here are the quick facts to help you get started:

Object Name: Messier 22

Alternative Designations: M22, NGC 6656

Object Type: Class VII Globular Star Cluster

Constellation: Sagittarius

Right Ascension: 18 : 36.4 (h:m)

Declination: -23 : 54 (deg:m)

Distance: 10.4 (kly)

Visual Brightness: 5.1 (mag)

Apparent Dimension: 32.0 (arc min)

Go on… Magnificent Messier 22 is waiting for you to appreciate it!

We have written many interesting articles about Messier Objects here at Universe Today. Here’s Tammy Plotner’s Introduction to the Messier Objects, , M1 – The Crab Nebula, M8 – The Lagoon Nebula, and David Dickison’s articles on the 2013 and 2014 Messier Marathons.

Be to sure to check out our complete Messier Catalog. And for more information, check out the SEDS Messier Database.

Sources: