Welcome back to Messier Monday! In our ongoing tribute to the great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at the Messier 21 open star cluster. Enjoy!

Back in the 18th century, famed French astronomer Charles Messier noted the presence of several “nebulous objects” in the night sky. Having originally mistaken them for comets, he began compiling a list of these objects so that other astronomers wouldn’t make the same mistake. Consisting of 100 objects, the Messier Catalog has come to be viewed as a major milestone in the study of Deep Space Objects.

One of these objects is Messier 21 (aka. NGC 6531), an open star cluster located in the Sagittarius constellation. A relatively young cluster that is tightly packed, this object is not visible to the naked eye. Hence why it was not discovered until 1764 by Charles Messier himself. It is now one of the over 100 Deep Sky Objects listed in the Messier Catalog.

Description:

At a distance of 4,250 light years from Earth, this group of 57 various magnitude stars all started life together about 4.6 million years ago as part of the Sagittarius OB1 stellar association. What makes this fairly loose collection of stars rather prized is its youth as a cluster, and the variation of age in its stellar members. Main sequence stars are easy enough to distinguish in a group, but low mass stars are a different story when it comes to separating them from older cluster members.

As Byeong Park of the Korean Astronomy Observatory said in a 2001 study of the object:

“In the case of a young open cluster, low-mass stars are still in the contraction phase and their positions in the photometric diagrams are usually crowded with foreground red stars and reddened background stars. The young open cluster NGC 6531 (M21) is located in the Galactic disk near the Sagittarius star forming region. The cluster is near to the nebula NGC 6514 (the Trifid nebula), but it is known that it is not associated with any nebulosity and the interstellar reddening is low and homogeneous. Although the cluster is relatively near, and has many early B-type stars, it has not been studied in detail.”

But study it in detail they did, finding 56 main sequence members, 7 pre-main sequence stars and 6 pre-main sequence candidates. But why did this cluster… you know, cluster in the way it did? As Didier Raboud, an astronomer from the Geneva Observatory, explained in his 1998 study “Mass segregation in very young open clusters“:

“The study of the very young open cluster NGC 6231 clearly shows the presence of a mass segregation for the most massive stars. These observations, combined with those concerning other young objects and very recent numerical simulations, strongly support the hypothesis of an initial origin for the mass segregation of the most massive stars. These results led to the conclusion that massive stars form near the center of clusters. They are strong constraints for scenarii of star and stellar cluster formation.” say Raboud, “In the context of massive star formation in the center of clusters, it is worth noting that we observe numerous examples of multiple systems of O-stars in the center of very young OCs. In the case of NGC 6231, 8 stars among the 10 brightest are spectroscopic binaries with periods shorter than 6 days.”

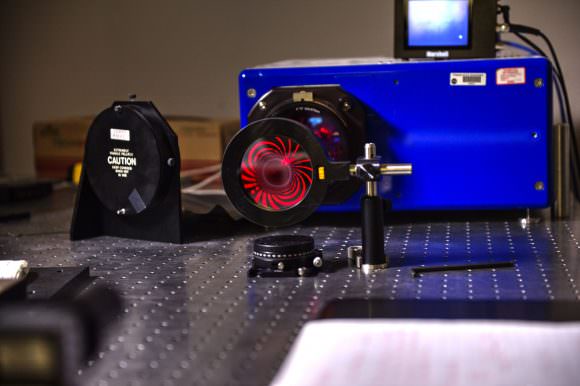

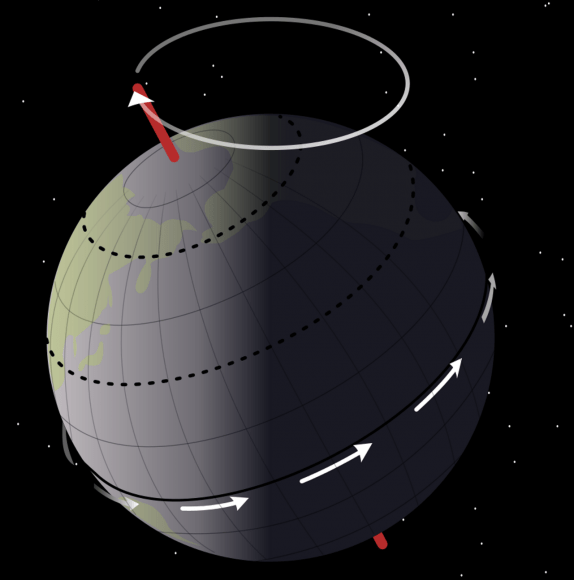

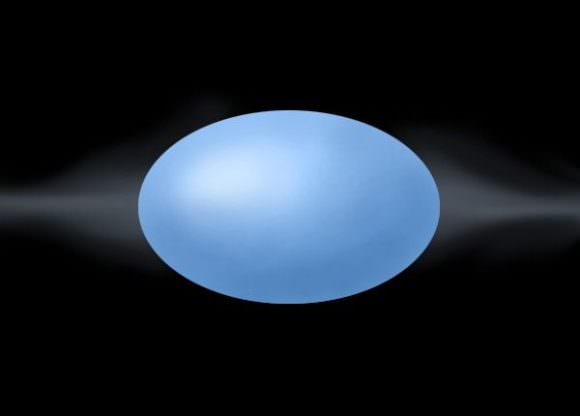

But are there any other surprises hidden inside? You bet! Try Be-stars, a class of rapidly rotating stars that end up becoming flattened at the poles. As Virginia McSwain of Yale University’s Department of Astronomy wrote in a 2005 study, “The Evolutionary Status of Be Stars: Results from a Photometric Study of Southern Open Clusters“:

“Be stars are a class of rapidly rotating B stars with circumstellar disks that cause Balmer and other line emission. There are three possible reasons for the rapid rotation of Be stars: they may have been born as rapid rotators, spun up by binary mass transfer, or spun up during the main-sequence (MS) evolution of B stars. To test the various formation scenarios, we have conducted a photometric survey of 55 open clusters in the southern sky. We use our results to examine the age and evolutionary dependence of the Be phenomenon. We find an overall increase in the fraction of Be stars with age until 100 Myr, and Be stars are most common among the brightest, most massive B-type stars above the zero-age main sequence (ZAMS). We show that a spin-up phase at the terminal-age main sequence (TAMS) cannot produce the observed distribution of Be stars, but up to 73% of the Be stars detected may have been spun-up by binary mass transfer. Most of the remaining Be stars were likely rapid rotators at birth. Previous studies have suggested that low metallicity and high cluster density may also favor Be star formation.”

History of Observation:

Charles Messier discovered this object on June 5th, 1764. As he wrote in his notes on the occassion:

“In the same night I have determined the position of two clusters of stars which are close to each other, a bit above the Ecliptic, between the bow of Sagittarius and the right foot of Ophiuchus: the known star closest to these two clusters is the 11th of the constellation Sagittarius, of seventh magnitude, after the catalog of Flamsteed: the stars of these clusters are, from the eighth to the ninth magnitude, environed with nebulosities. I have determined their positions. The right ascension of the first cluster, 267d 4′ 5″, its declination 22d 59′ 10″ south. The right ascension of the second, 267d 31′ 35″; its declination, 22d 31′ 25″ south.”

While Messier did separate the two star clusters, he assumed the nebulosity of M20 was also involved with M21. In this circumstance, we cannot fault him. After all, his job was to locate comets, and the purpose of his catalog was to identify those objects that were not. In later years, Messier 21 would be revisited again by Admiral Smyth, who would describe it as follows:

“A coarse cluster of telescopic stars, in a rich gathering galaxy region, near the upper part of the Archer’s bow; and about the middle is the conspicuous pair above registered, – A being 9, yellowish, and B 10, ash coloured. This was discovered by Messier in 1764, who seems to have included some bright outliers in his description, and what he mentions as nebulosity, must have been the grouping of the minute stars in view. Though this was in the power of the meridian instruments, its mean apparent place was obtained by differentiation from Mu Sagittarii, the bright star about 2 deg 1/4 to the north-east of it.”

Locating Messier 21:

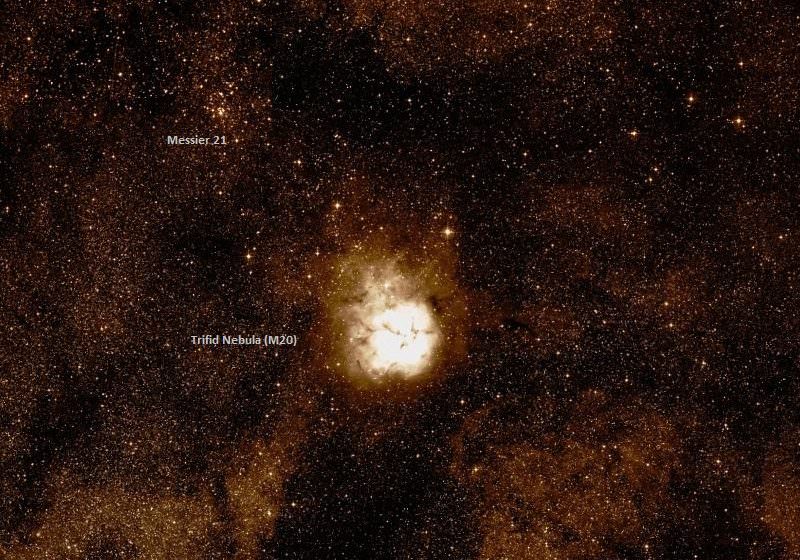

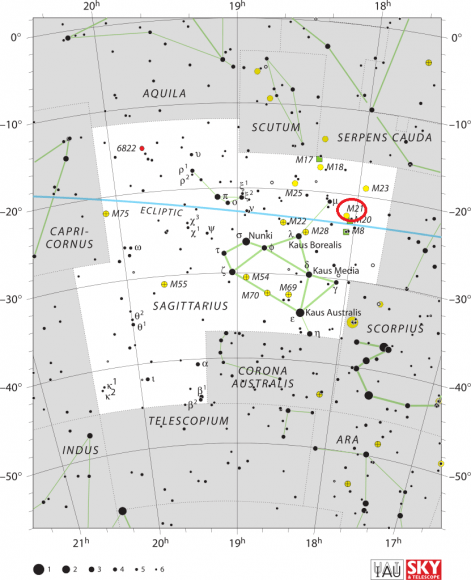

Once you have become familiar with the Sagittarius region, finding Messier 21 is easy. It’s located just two and a half degrees northwest of Messier 8 – the “Lagoon Nebula” – and about a half a degree northeast of Messier 20 – the “Trifid Nebula“. If you are just beginning to astronomy, try starting at the teapot’s tip star (Lambda) “Al Nasl”, and starhopping in the finderscope northwest to the Lagoon.

While the nebulosity might not show in your finder, optical double 7 Sagittari, will. From there you will spot a bright cluster of stars two degrees due north. These are the stars embedded withing the Trifid Nebula, and the small, compressed area of stars to its northeast is the open star cluster M21. It will show well in binoculars under most sky conditions as a small, fairly bright concentration and resolve well for all telescope sizes.

And here are the quick facts, for your convenience:

Object Name: Messier 21

Alternative Designations: M21, NGC 6531

Object Type: Open Star Cluster

Constellation: Sagittarius

Right Ascension: 18 : 04.6 (h:m)

Declination: -22 : 30 (deg:m)

Distance: 4.25 (kly)

Visual Brightness: 6.5 (mag)

Apparent Dimension: 13.0 (arc min)

We have written many interesting articles about Messier Objects here at Universe Today. Here’s Tammy Plotner’s Introduction to the Messier Objects, , M1 – The Crab Nebula, M8 – The Lagoon Nebula, and David Dickison’s articles on the 2013 and 2014 Messier Marathons.

Be to sure to check out our complete Messier Catalog. And for more information, check out the SEDS Messier Database.

Sources: