Ever since human beings learned that the Milky Way was not unique or alone in the night sky, astronomers and cosmologists have sought to find out just how many galaxies there are in the Universe. And until recently, our greatest scientific minds believed they had a pretty good idea – between 100 and 200 billion.

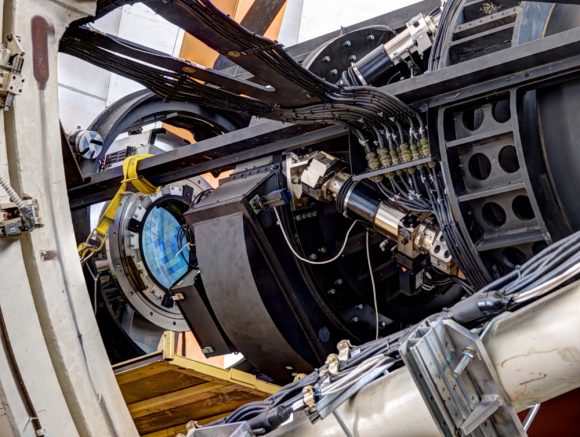

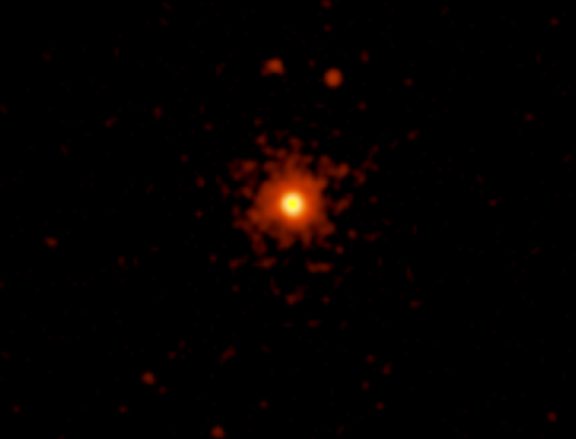

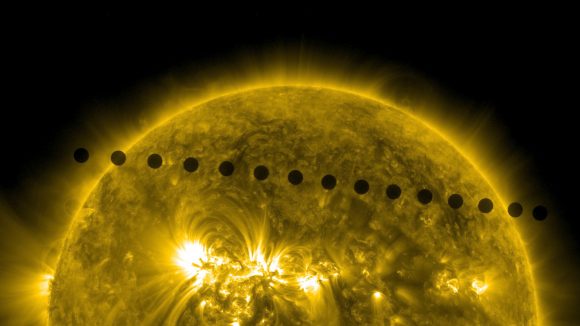

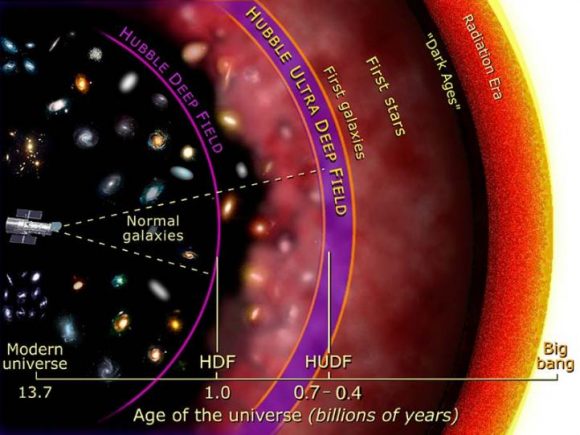

However, a new study produced by researchers from the UK has revealed something startling about the Universe. Using Hubble’s Deep Field Images and data from other telescopes, they have concluded that these previous estimates were off by a factor of about 10. The Universe, as it turns out, may have had up to 2 trillion galaxies in it during the course of its history.

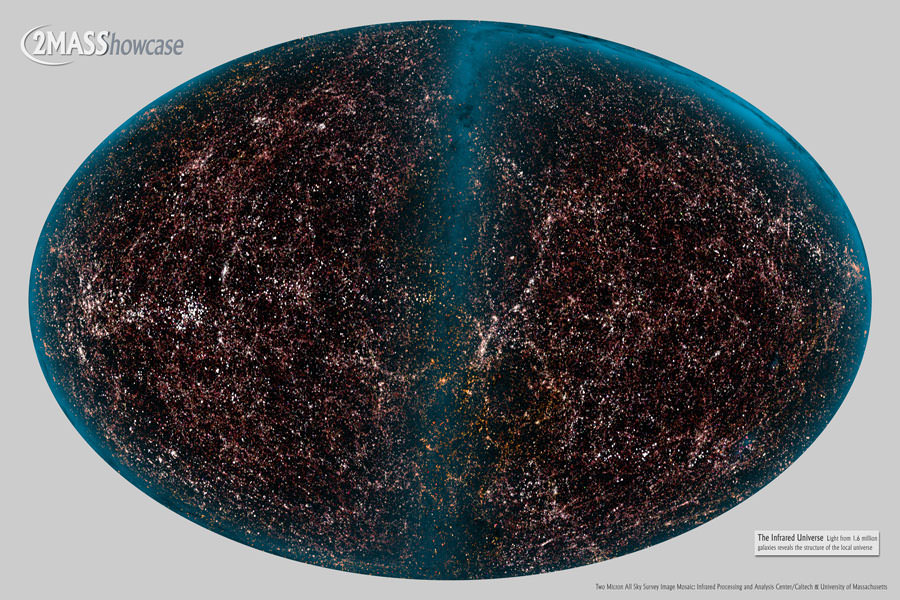

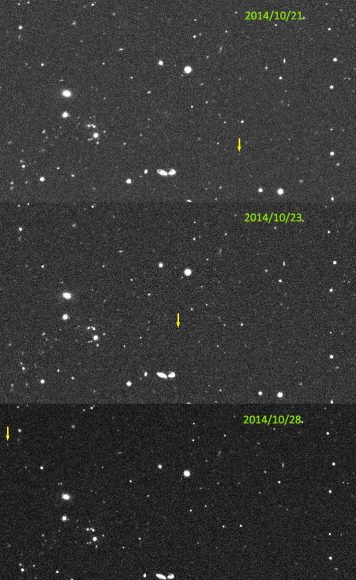

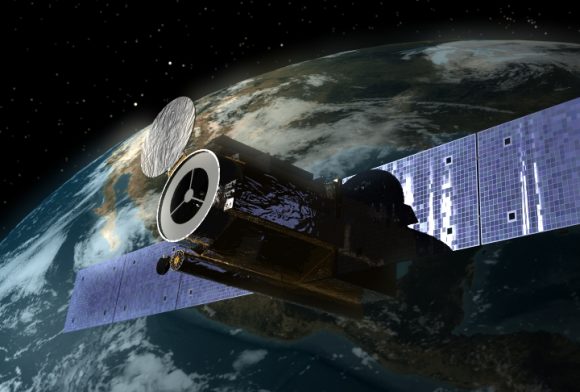

Led by Prof. Christopher Conselice of the University of Nottingham, U.K., the team combined images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope with other published data to produced a 3-D map of the Universe. They then incorporated a series of new mathematical models that allowed them to infer the existence of galaxies which are not bright enough to be observed by current instruments.

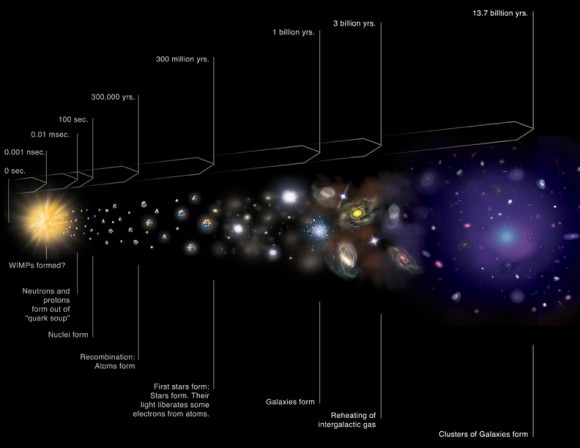

Using these, they then began reviewing how galaxies have evolved over the past 13 billion years. What they learned was quite fascinating. For one, they observed that the distribution of galaxies throughout the history of the Universe was not even. What’s more, they found that in order for everything in their calculations to add up, there had to be 10 times more galaxies in the early Universe than previously thought.

Most of these galaxies would be similar in mass to the satellite galaxies that have been observed around the Milky Way, and would be too faint to be spotted by today’s instruments. In other words, astronomers have only been able to see about 10% of the early Universe until now, because most of its galaxies were too small and faint to be visible.

As Prof. Conselice explained in a Hubble Science Release, while may help resolve a lingering debate about the structure of the Universe:

“These results are powerful evidence that a significant galaxy evolution has taken place throughout the universe’s history, which dramatically reduced the number of galaxies through mergers between them — thus reducing their total number. This gives us a verification of the so-called top-down formation of structure in the universe.”

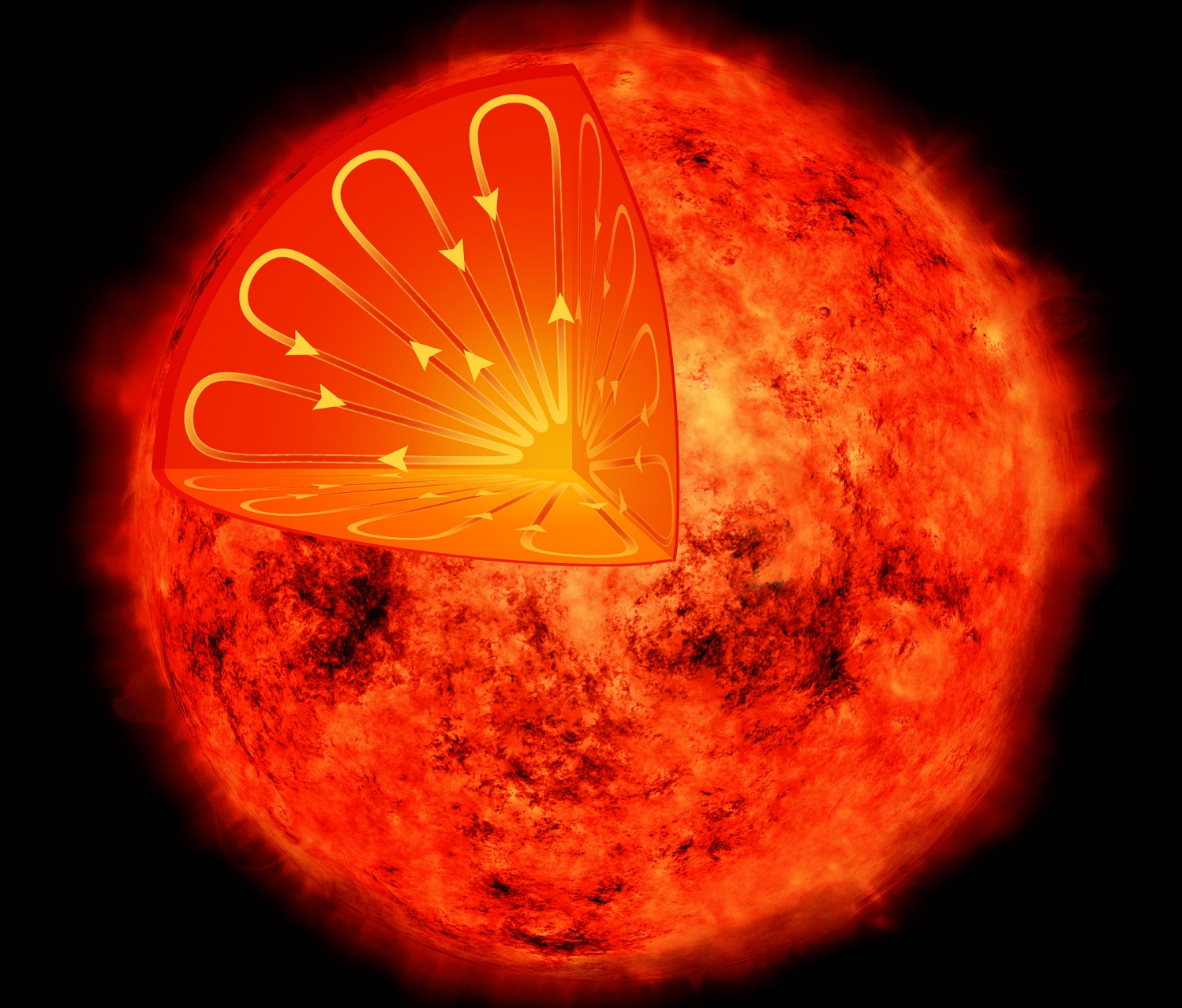

To break it down, the “top-down model” of galaxy formation states that galaxies formed from huge gas clouds larger than the resulting galaxies. These clouds began collapsing because their internal gravity was stronger than the pressures in the cloud. Based on the speed at which the gas clouds rotated, they would either form a spiral or an elliptical galaxy.

In contrast, the “bottom-up model” states that galaxies formed during the early Universe due to the merging of smaller clumps that were about the size globular clusters. These galaxies could then have been drawn into clusters and superclusters by their mutual gravity.

In addition to helping to resolve this debate, this study also offers a possible solution to the Olbers’ Paradox (aka. “the dark night sky paradox”). Named after the 18th/19th century German astronomer Heinrich Wilhelm Olbers, this paradox addresses the question of why – given the expanse of the Universe and all the luminous matter in it – is the sky dark at night?

Based on their results, the UK team has surmised that while every point in the night sky contains part of a galaxy, most of them are invisible to the human eye and modern telescopes. This is due to a combination of factors, which includes the effects of cosmic redshift, the fact that the Universe is dynamic (i.e. always expanding) and the absorption of light by cosmic dust and gas.

Needless to say, future missions will be needed to confirm the existence of all these unseen galaxies. And in that respect, Conselice and his colleagues are looking to future missions – ones that are capable of observing stars and galaxies in the non-visible spectrum – to make that happen.

“It boggles the mind that over 90 percent of the galaxies in the universe have yet to be studied,” he added. “Who knows what interesting properties we will find when we discover these galaxies with future generations of telescopes? In the near future, the James Webb Space Telescope will be able to study these ultra-faint galaxies.”

Understanding how many galaxies have existed over time is a fundamental aspect of understanding the Universe as a whole. With every passing study that attempts to resolve what we can see with our current cosmological models, we are getting that much closer!

And be sure to enjoy this video about some of Hubble’s most stunning images, courtesy of HubbleESA:

Further Reading: HubbleSite, Hubble Space Telescope