Welcome back to Messier Monday! In our ongoing tribute to the great Tammy Plotner, we take a look at the Messier 16 open star cluster – aka. The Eagle Nebula (and a slew of other names). Enjoy!

In the 18th century, while searching the night sky for comets, French astronomer Charles Messier began noticing a series of “nebulous objects” in the night sky. Hoping to ensure that other astronomers did not make the same mistake, he began compiling a list of these objects,. Known to posterity as the Messier Catalog, this list has come to be one of the most important milestones in the research of Deep Sky objects.

One of these objects it he Eagle Nebula (aka. NGC 661. The Star Queen Nebula and The Spire), a young open cluster of stars located in the Serpens constellation. The names “Eagle” and “Star Queen” refer to visual impressions of the dark silhouette near the center of the nebula. The nebula contains several active star-forming gas and dust regions, which includes the now-famous “Pillars of Creation“.

Description:

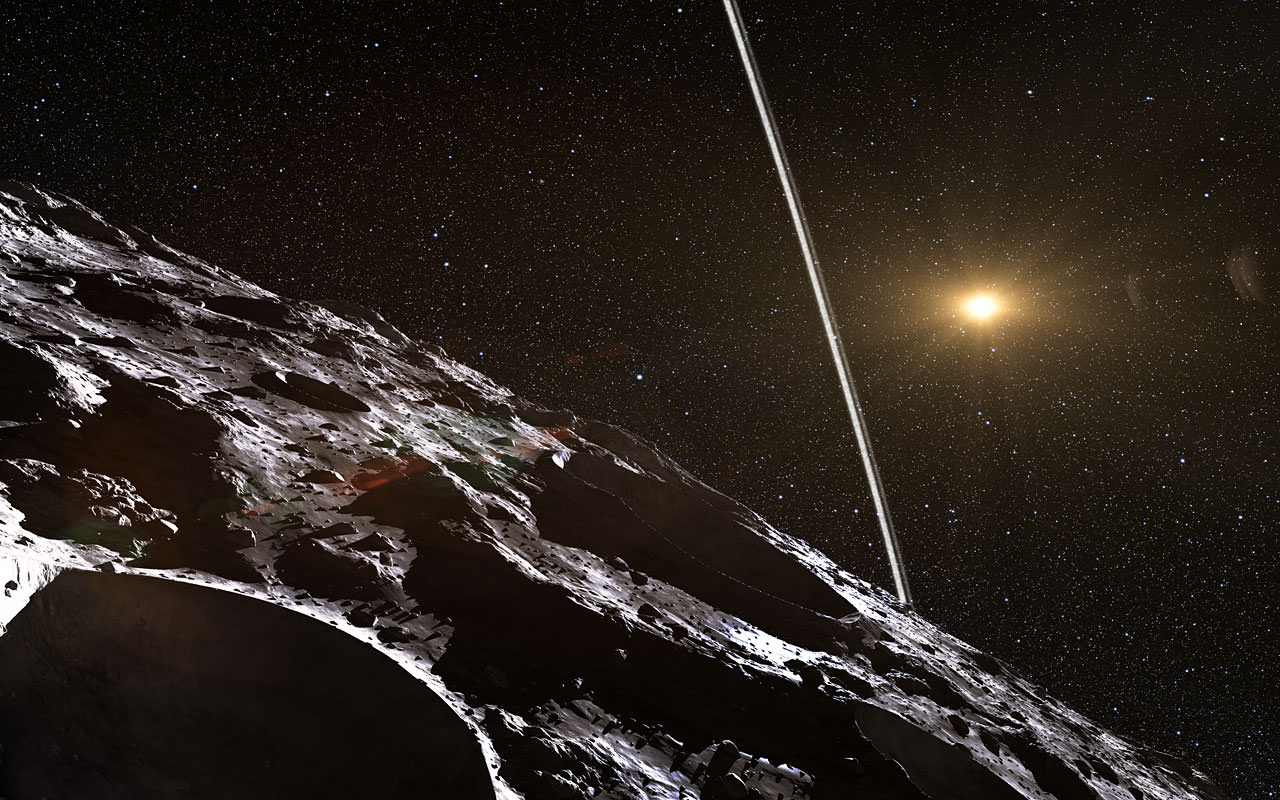

Located some 7,000 light years away in the next inner spiral arm of the Milky Way galaxy, the Eagle Nebula spans some 70 by 50 light years across. Born around 5.5 million years ago, this glittering swarm marks an area about 15 light years wide, and within the heart of this nebula is a cluster of stars and a region that has captured our imaginations like nothing else – the “Pillars of Creation”.

Here, star formation is going on. The dust clouds are illuminated by emission light, where high-energy radiation from its massive and hot young stars excited the particles of gas and makes them glow. Inside the pillars are Evaporating Gaseous Globules (EGGs), concentrations of gas that are emerging from the “womb” that about to become stars.

These pockets of interstellar gas are dense enough to collapse under their own weight, forming young stars that continue to grow as they accumulate more and more mass from their surroundings. As their place of birth contracts gravitationally, the interior gas reaches its end and the intense radiation of bright young stars causes low density material to boil away.

These regions were first photographed by the Hubble Space Telescope in 1995. As Jeff Hester – a professor at Arizona State University and an investigator with the Hubble’s Wide Field and Planetary Camera 2 (WFPC2) – said of the discovery:

“For a long time astronomers have speculated about what processes control the sizes of stars – about why stars are the sizes that they are. Now in M16 we seem to be watching at least one such process at work right in front of our eyes.”

The Hubble has shown us what happens when all the gas boils away and only the EGGs are left. “It’s a bit like a wind storm in the desert,” said Hester. “As the wind blows away the lighter sand, heavier rocks buried in the sand are uncovered. But in M16, instead of rocks, the ultraviolet light is uncovering the denser egg-like globules of gas that surround stars that were forming inside the gigantic gas columns.”

And some of these EGGs are nothing more than what would appear to be tiny bumps and teardrops in space – but at least we are looking back in time to see what stars look like when they were first born. “This is the first time that we have actually seen the process of forming stars being uncovered by photoevaporation,” Hester emphasized. “In some ways it seems more like archaeology than astronomy. The ultraviolet light from nearby stars does the digging for us, and we study what is unearthed.”

History of Observation:

The star cluster associated with M16 (NGC 6611) was first discovered by Philippe Loys de Chéseaux in 1745-6. However, it was Charles Messier who was the very first to see the nebulosity associated with it. As he recorded in his notes:

“In the same night of June 3 to 4, 1764, I have discovered a cluster of small stars, mixed with a faint light, near the tail of Serpens, at little distance from the parallel of the star Zeta of that constellation: this cluster may have 8 minutes of arc in extension: with a weak refractor, these stars appear in the form of a nebula; but when employing a good instrument one distinguishes these stars, and one remarks in addition a nebulosity which contains three of these stars. I have determined the position of the middle of this cluster; its right ascension was 271d 15′ 3″, and its declination 13d 51′ 44″ south.”

Oddly enough, Sir William Herschel, who was famous for elaborating on Messier’s observations, didn’t seem to notice the nebula at all (according to his notes). And Admiral Smyth, who could always be counted on for flowery prose about stellar objects, just barely saw it as well:

“A scattered but fine large stellar cluster, on the nombril of Sobieski’s shield, in the Galaxy, discovered by Messier in 1764, and registered as a mass of small stars in the midst of a faint light. As the stars are disposed in numerous pairs among the evanescent points of more minute components, it forms a very pretty object in a telescope of tolerable capacity.”

But of course, the nebula isn’t an easy object to spot and its visibility on any given night depends greatly on sky conditions. As historical evidence suggest, only one of the two masters (Messier) caught it. So take a lesson from history and return to the sky many times. One day you’ll be rewarded!

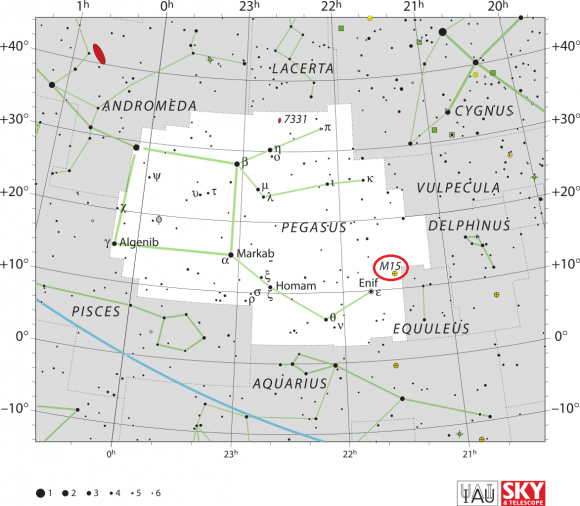

Locating Messier 16:

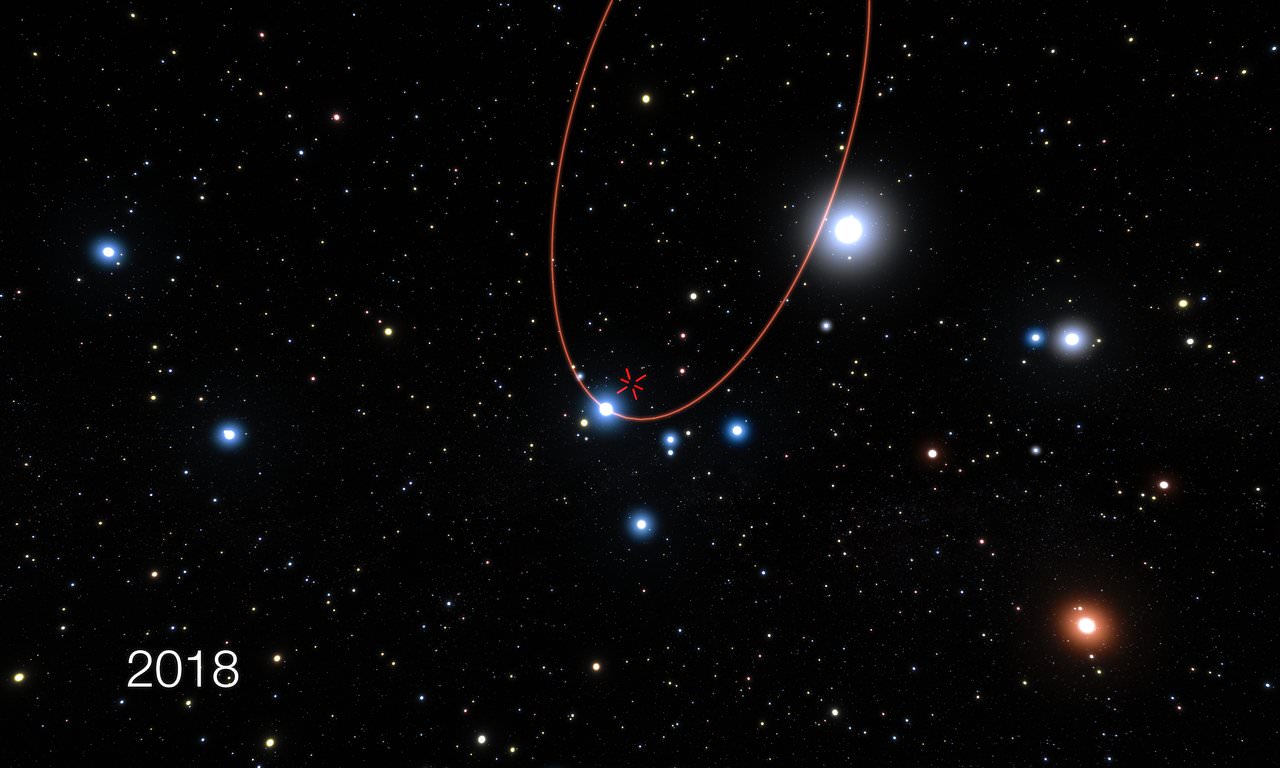

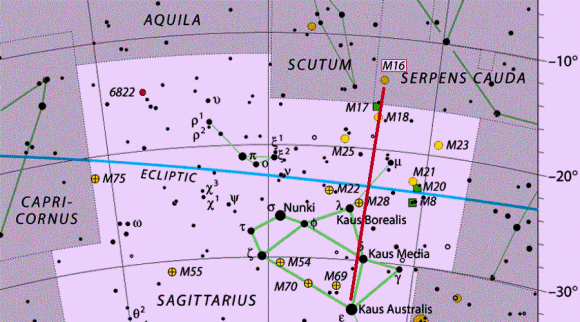

One of the easiest ways to find M16 is to identify the constellation of Aquila and begin tracing the stars down the eagle’s back to Lambda. When you reach that point, continue to extend the line through to Alpha Scuti, then southwards towards Gamma Scuti. Aim your binoculars or image correct finderscope at Gamma and put it in the 7:00 position.

For those using a finderscope, M16 will easily show up as a faint haze. Even those using binoculars won’t miss it. If Gamma is in the lower left hand corner of your vision – then M16 is in the upper right hand. For all optics, you won’t be able to miss the open star cluster and the faint nebulosity of IC 4703 can be seen from dark sky locations.

Another way to find M16 is by first locating the “Teapot” asterism in Sagittarius constellation (see above), and then by following the line from the star Kaus Australis (Epsilon Sagittarii) – the brightest star in Sagittarius – to just east of Kaus Media (Delta Sagittarii). Another way to find the nebula is by extending a line from Lambda Scuti in Scutum constellation to Alpha Scuti, and then to the south to Gamma Scuti.

Those using large aperture telescopes will be able to see the nebula well, but sky conditions are everything when it comes to this one. The star cluster which is truly M16 will always be easy, but the nebula is a challenge.

And as always, here are the quick facts on M16 to help you get started:

Object Name: Messier 16

Alternative Designations: M16, NGC 6611, Eagle Nebula (IC 4703)

Object Type: Open Star Cluster and Emission Nebula

Constellation: Serpens (Cauda)

Right Ascension: 18 : 18.8 (h:m)

Declination: -13 : 47 (deg:m)

Distance: 7.0 (kly)

Visual Brightness: 6.4 (mag)

Apparent Dimension: 7.0 (arc min)

And be sure to enjoy this video of the Eagle Nebula and the amazing photographs of the “Pillar of Creation”:

We have written many interesting articles about Messier Objects here at Universe Today. Here’s Tammy Plotner’s Introduction to the Messier Objects, , M1 – The Crab Nebula, M8 – The Lagoon Nebula, and David Dickison’s articles on the 2013 and 2014 Messier Marathons.

Be to sure to check out our complete Messier Catalog. And for more information, check out the SEDS Messier Database.