Our Solar System is a fascinating place. Between its eight planets and many dwarf planets, there are some serious differences in terms of orbit, composition, and temperature. Whereas conditions within the inner Solar System, where planets are terrestrial in nature, can get pretty hot, planets that orbit beyond the Frost Line – where it is cold enough that volatiles (i.e. water, ammonia, methane, CO and CO²) condense into solids – can get mighty cold!

It is in this environment that we find Neptune, the Solar System’s most distance (and hence most cold) planet. While this gas/ice giant has no “surface” to speak of, Earth-based research and flybys have been conducted that have managed to obtain accurate measurements of the temperature in the planet’s upper atmosphere. All told, the planet experiences temperatures that range from approximately 55 K (-218 °C; -360 °F) to 72 K (-200 °C; -328 °F), making it the coldest planet in the Solar System.

Orbital Characteristics:

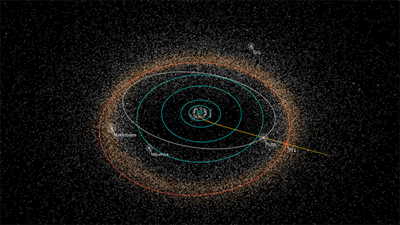

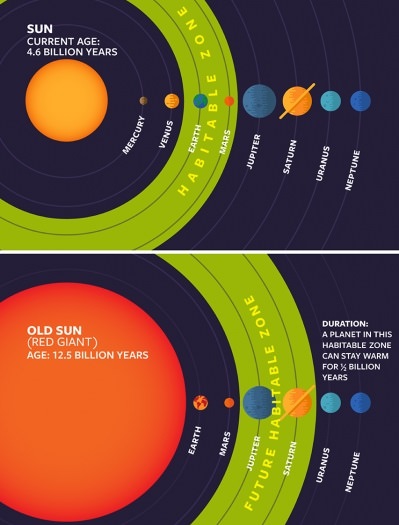

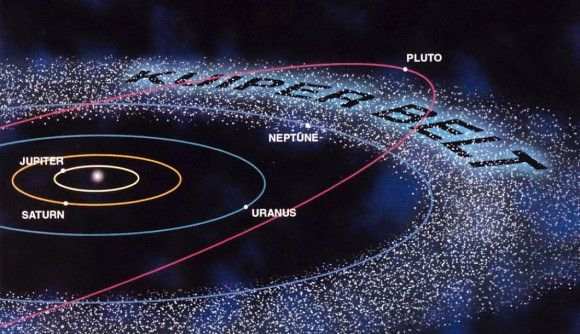

Of all the planets in the Solar System, Neptune orbits the Sun at the greatest average distance. With a very minor eccentricity (0.0086), it orbits the Sun at an semi-major axis of approximately 30.11 AU (4,504,450,000,000 km), ranging from 29.81 AU (4.459 x 109 km) at perihelion and 30.33 AU (4.537 x 109 km) at aphelion.

Neptune takes 16 hours 6 minutes and 36 seconds (0.6713 days) to complete a single sidereal rotation, and 164.8 Earth years to complete a single orbit around the Sun. This means that a single day lasts 67% as long on Neptune, whereas a year is the equivalent of approximately 60,190 Earth days (or 89,666 Neptunian days).

Because Neptune’s axial tilt (28.32°) is similar to that of Earth (~23°) and Mars (~25°), the planet experiences similar seasonal changes. Combined with its long orbital period, this means that the seasons last for forty Earth years. In addition, the planets axial tilt also leads to variations in the length of its day, as well as variations in temperature between the northern and southern hemispheres (see below).

“Surface” Temperature:

Due to their composition, determining a surface temperature on gas or ice giants (compared to terrestrial planets or moons) is technically impossible. As a result, astronomers have relied on measurements obtained at altitudes where the atmospheric pressure is equal to 1 bar (or 100 kilo Pascals), the equivalent of air pressure here on Earth at sea level.

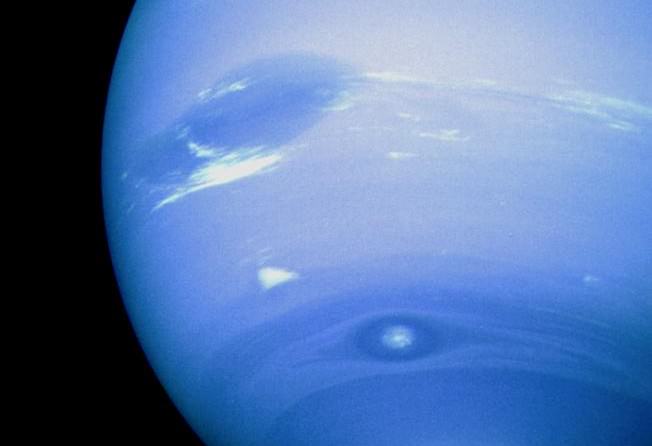

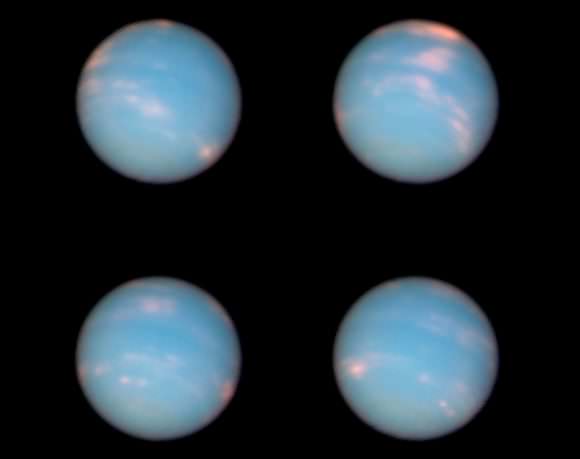

It is here on Neptune, just below the upper level clouds, that pressures reach between 1 and 5 bars (100 – 500 kPa). It is also at this level that temperatures reach their recorded high of 72 K (-201.15 °C; -330 °F). At this temperature, conditions are suitable for methane to condense, and clouds of ammonia and hydrogen sulfide are thought to form (which is what gives Neptune its characteristically dark cyan coloring).

But as with all gas and ice giants, temperatures vary on Neptune due to depth and pressure. In short, the deeper one goes into Neptune, the hotter it becomes. At its core, Neptune reaches temperatures of up to 7273 K (7000 °C; 12632 °F), which is comparable to the surface of the Sun. The huge temperature differences between Neptune’s center and its surface create huge wind storms, which can reach as high as 2,100 km/hour, making them the fastest in the Solar System.

Temperature Anomalies and Variations:

Whereas Neptune averages the coldest temperatures in the Solar System, a strange anomaly is the planet’s south pole. Here, it is 10 degrees K warmer than the rest of planet. This “hot spot” occurs because Neptune’s south pole is currently exposed to the Sun. As Neptune continues its journey around the Sun, the position of the poles will reverse. Then the northern pole will become the warmer one, and the south pole will cool down.

Neptune’s more varied weather when compared to Uranus is due in part to its higher internal heating, which is particularly perplexing for scientists. Despite the fact that Neptune is located over 50% further from the Sun than Uranus, and receives only 40% its amount of sunlight, the two planets’ surface temperatures are roughly equal.

Deeper inside the layers of gas, the temperature rises steadily. This is consistent with Uranus, but oddly enough, the discrepancy is larger. Uranus only radiates 1.1 times as much energy as it receives from the Sun, whereas Neptune radiates about 2.61 times as much. Neptune is the farthest planet from the Sun, yet its internal energy is sufficient to drive the fastest planetary winds seen in the Solar System. The mechanism for this remains unknown.

And while temperatures on Pluto have been recorded as reaching lower – down to 33 K (-240 °C; -400 °F) – Pluto’s status as a dwarf planet mean that it is no longer in the same class as the others. As such, Neptune remains the coldest planet of the eight.

We have written many articles about Neptune here at Universe Today. Here’s The Gas (and Ice) Giant Neptune, What is the Surface of Neptune Like?, 10 Interesting Facts About Neptune, and The Rings of Neptune.

If you’d like more information on Neptune, take a look at Hubblesite’s News Releases about Neptune, and here’s a link to NASA’s Solar System Exploration Guide to Neptune.

We have recorded an entire episode of Astronomy Cast just about Neptune. You can listen to it here, Episode 63: Neptune.