We’ve solved many of the problems associated with space travel. Humans can spend months in the zero-gravity of space, they can perform zero-gravity space-walks and repair spacecraft, they can walk on the surface of the Moon, and they can even manage, ahem, personal hygiene in space. We’re even making progress in understanding how to grow food in space. But one thing remains uncertain: can we make baby humans in space?

According to a recent successful Chinese experiment, the answer is a tentative yes. Sort of.

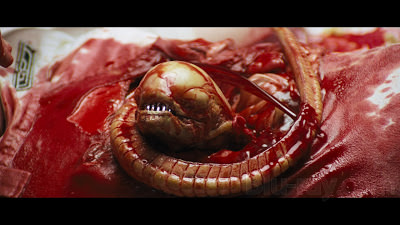

The Chinese performed a 96-hour experiment to test the viability of mammal embryos in space. They placed 6,000 mouse embryos in a micro-wave sized chamber aboard a satellite, to see if they would develop into blastocysts. The development of embryos into blastocysts is a crucial step in reproduction. Once the blastocysts have developed, they attach themselves to the wall of the uterus. Cameras on the inside of the chamber allowed Chinese scientists on Earth to monitor the experiment.

Duan Enkui, from the Chinese Academy of Sciences, who is the principal researcher for this experiment, told China Daily “The human race may still have a long way to go before we can colonise space, but before that we have to figure out whether it is possible for us to survive and reproduce in the outer space environment like we do on Earth.”

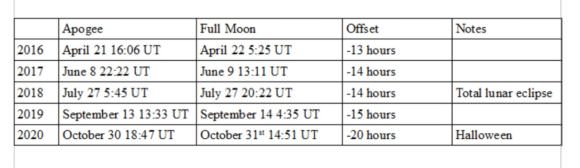

The Chinese say some of the embryos became blastocysts, and are claiming success in an endeavour that others have tried and failed at. NASA has performed similar experiments on Earth, where the micro-gravity conditions in space were duplicated. A study from 2009 showed that fertilization occurred normally in micro-gravity environments, but the eventual birth rate for the micro-gravity subjects was lower than for a 1G control group. The results from this study concluded that normal Earth gravity might be necessary for the blastocysts to successfully attach themselves to the uterus.

It’s important to note that at this point that China has proclaimed success by saying “some” of the embryos developed. But how many? There were 6,000 of them. Until they attach numbers to their claim, the word “some” doesn’t tell us much in terms of humans colonizing space. It also doesn’t tell us whether or not the crucial blastocyst to uterus attachment is inhibited by micro-gravity. Call us pedantic here at Universe Today, but it’s kind of important to know the numbers.

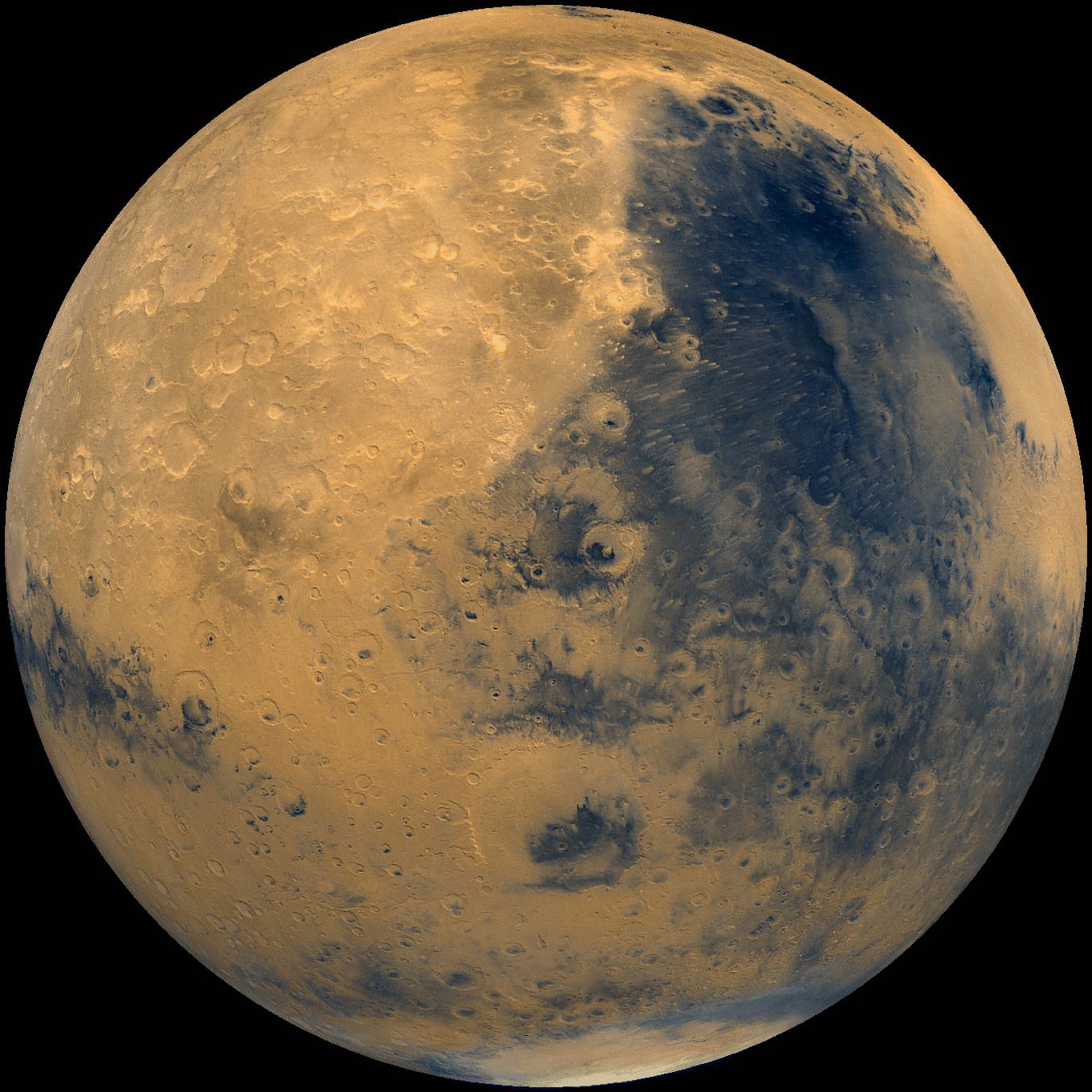

On the other hand, an increase in scientific curiosity related to procreating in space is a healthy development. The ideas and plans for missions to Mars and an eventual long-term presence in space are heating up. Making babies in space might not that relevant right now, but issues have a way of sneaking up on us.

The full results of this Chinese experiment will be interesting, if and when they’re made public. They may help clarify one aspect of the whole “making babies in space” problem. But in the bigger picture, things are still a little cloudy.

On shuttle mission STS-80, 2-cell mouse embryos were taken into space micro-gravity for 4 days. None of them developed into blastocysts, while a control group on the ground did. Another experiment in 1979, aboard Cosmos 1129, had male and female rats aboard. Though post-experiment results showed that some of the female rats had indeed ovulated, none of them gave birth. Two of the females even got pregnant, but the fetuses were reportedly r-absorbed.

Still, we have to give credit where its due. And the Chinese study has shown that mammal blastocysts can develop from embryos in micro-gravity. Still, there’s more to the space environment than low gravity. The radiation environment is much different. One study called the Space Pup study, led by principal investigator Teruhiko Wakayama, from the Riken Center for Developmental Biology, Japan, hopes to shed some light on that aspect of reproduction in space.

Space Pup will take sample of freeze-dried mouse sperm to the ISS for periods of 1, 12, and 24 months. Then, the samples will be returned to Earth and be used to fertilize mouse eggs.

There’s a lot more to learn in the area of reproduction in space. The next steps will involve keeping live mammals in space to monitor their reproduction. It’s not like ISS astronauts need more work to do, but maybe they’ll like having some animals along for company.

Maybe we’ll need to think outside the box when it comes to procreation in space. Maybe some type of in-vitro procedure will help humans spread the love in space. Or maybe, we’ll need to look to science fiction for inspiration. After all, countless alien species seem to be able to reproduce effectively, given the right circumstances.