Have you ever seen Mercury? The diminutive innermost world takes the center stage next month, as it transits the Sun as seen from our early perspective on May 9th. This week, we’d like to turn your attention to bashful Mercury’s dusk apparition, which sets up the clockwork celestial gears for this event. Continue reading “Prelude to Transit: Catching Mercury Under Dusk Skies”

Messier 11 (M11) – The Wild Duck Cluster

Welcome back to another edition of Messier Monday! Today, we continue in our tribute to Tammy Plotner with a look at the M11 Wild Duck Cluster!

In the 18th century, French astronomer Charles Messier noted the presence of several “nebulous objects” in the night sky while searching for comets. Hoping to ensure that other astronomers did not make the same mistake, he began compiling a list of 1oo of them. This list came to be known as the Messier Catalog, and would have far-reaching consequences.

One of these objects is M11, otherwise known as The Wild Duck Cluster, an open cluster located in the constellation Scutum, near the northern edge of a rich Milky Way star cloud (the Scutum Cloud). This open star cluster is one of the richest and most compact of all those known, composed of a few thousand hot, young stars that are only a few million years old.

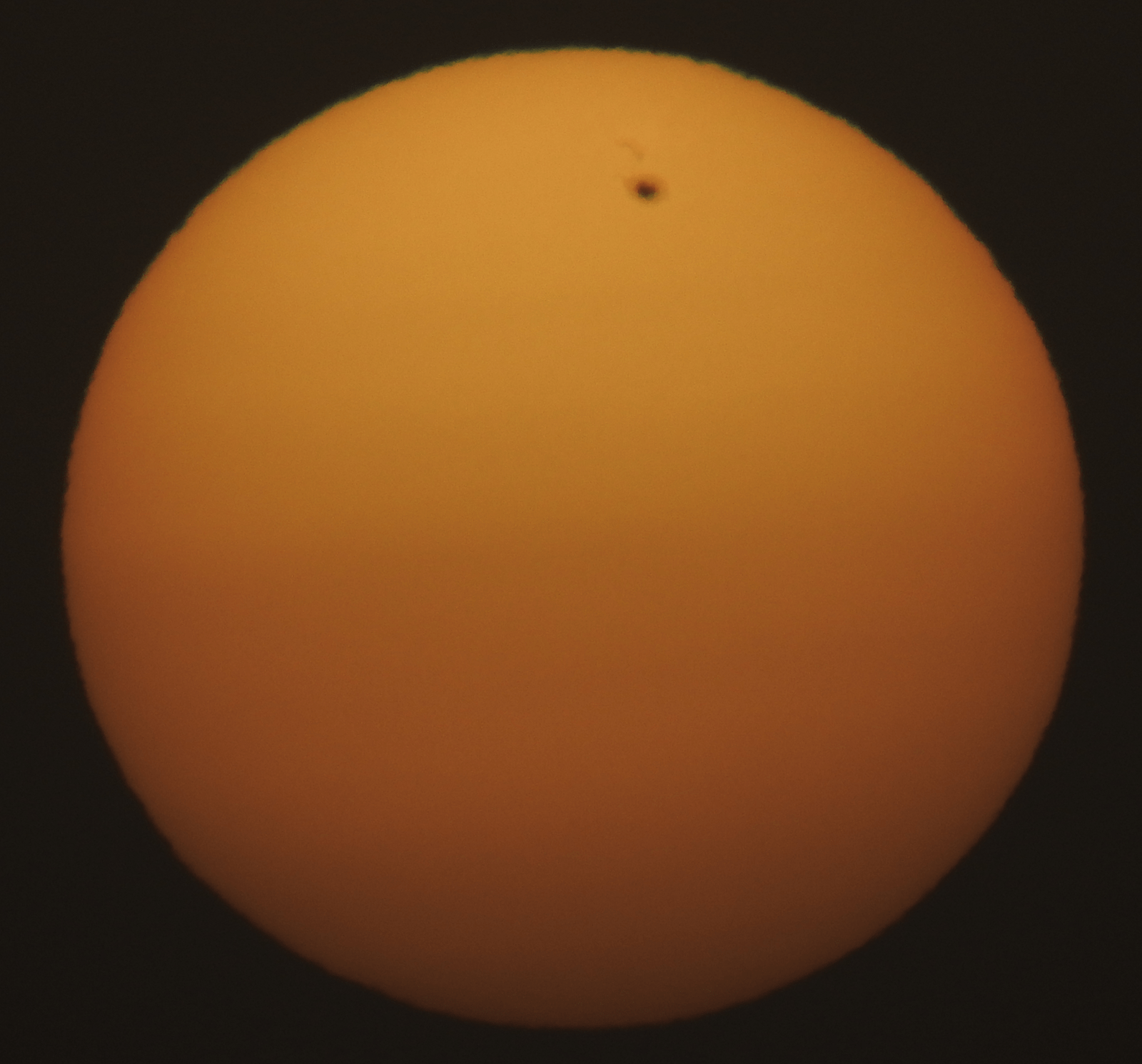

Huge Sunspot Turns Earthward

Our seemly placid host star is just full of surprises.

Just one week ago, it looked like we were set to enter the first spotless stretch of 2016, as the Earthward face of Sol presented one lonely sunspot group going ’round the limb, headed towards the solar far side. Continue reading “Huge Sunspot Turns Earthward”

Can We Now Predict When A Neutron Star Will Give Birth To A Black Hole?

A neutron star is perhaps one of the most awe-inspiring and mysterious things in the Universe. Composed almost entirely of neutrons with no net electrical charge, they are the final phase in the life-cycle of a giant star, born of the fiery explosions known as supernovae. They are also the densest known objects in the universe, a fact which often results in them becoming a black hole if they undergo a change in mass.

For some time, astronomers have been confounded by this process, never knowing where or when a neutron star might make this final transformation. But thanks to a recent study by a team of researchers from Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany, it may now be possible to determine the absolute maximum mass that is required for a neutron star to collapse, giving birth to a new black hole.

Continue reading “Can We Now Predict When A Neutron Star Will Give Birth To A Black Hole?”

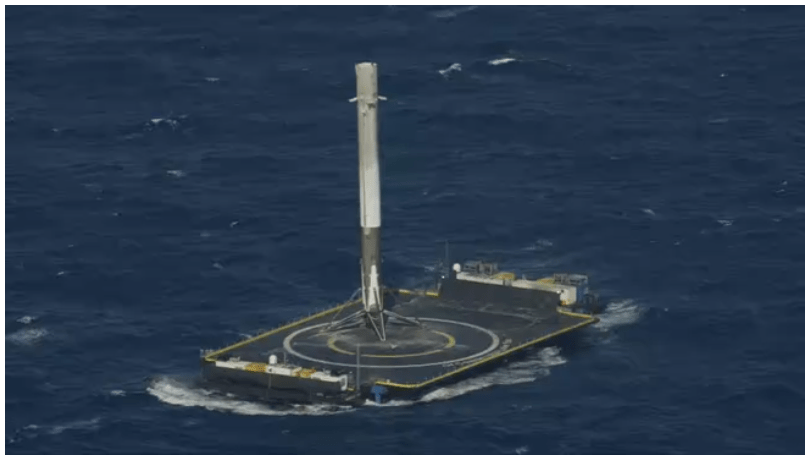

SpaceX Achieves Historic Landing!

In their drive to achieve the goal of reusable rockets, SpaceX has spent the past few years running their Falcon 9 rocket through the most rigorous of tests. And while they have achieved a soft landing once before, SpaceX has been unable to safely land their rockets at sea, despite several attempts. This has been an important step in the development process, as it would mean that the Falcon 9 can be landed under the most difficult of conditions.

But earlier today, SpaceX finally reached that milestone as their CRS-08 mission, which was launched from Cape Canaveral at 4:43 pm (ET), made it back to Earth in one piece. After sending its payload of a Dragon Capsule to rendezvous with the International Space Station, the first-stage rocket successfully made a soft landing on a drone ship in the Atlantic Ocean. This one achievement brings SpaceX one step closer to fulfilling the goal Musk founded the company upon, which is achieving cost-effective, commercial spaceflight.

A Star With A Disk Of Water Ice? Meet HD 100546

It might seem incongruous to find water ice in the disk of gas and dust surrounding a star. Fire and ice just don’t mix. We would never find ice near our Sun.

But our Sun is old. About 5 billion years old, with about 5 billion more to go. Some younger stars, of a type called Herbig Ae/Be stars (after American astronomer George Herbig,) are so young that they are surrounded by a circumstellar disk of gas and dust which hasn’t been used up by the formation of planets yet. For these types of stars, the presence of water ice is not necessarily unexpected.

Water ice plays an important role in a young solar system. Astronomers think that water ice helps large, gaseous, planets to form. The presence of ice makes the outer section of a planetary disk more dense. This increased density allows the cores of gas planets to coalesce and form.

Young solar systems have what is called a snowline. It is the boundary between terrestrial and gaseous planets. Beyond this snowline, ice in the protoplanetary disk encourages gas planets to form. Inside this snowline, the lack of water ice contributes to the formation of terrestrial planets. You can see this in our own Solar System, where the snowline must have been between Mars and Jupiter.

A team of astronomers using the Gemini telescope observed the presence of water ice in the protoplanetary disk surrounding the star HD 100546, a Herbig Ae/Be star about 320 light years from us. At only 10 million years old, this star is rather young, and it is a well-studied star. The Hubble has found complex, spiral patterns in the disk, and so far these patterns are unexplained.

HD 100546 is also notable because in 2013, research showed the probable ongoing formation of a planet in its disk. This presented a rare opportunity to study the early stages of planet formation. Finding ice in the disk, and discovering how deep it exists in the disk, is a key piece of information in understanding planet formation in young solar systems.

Finding this ice took some clever astro-sleuthing. The Gemini telescope was used, with its Near-Infrared Coronagraphic Imager (NICI), a tool used to study gas giants. The team installed H2O ice filters to help zero in on the presence of water ice. The protoplanetary disk around young stars, as in the case of HD 100546, is a mixed up combination of dusts and gases, and isolating types of materials in the disk is not easy.

Water ice has been found in disks around other Herbig Ae/Be stars, but the depth of distribution of that ice has not been easy to understand. This paper shows that the ice is present in the disk, but only shallowly, with UV photo desorption processes responsible for destroying water ice grains closer to the star.

It may seem trite so say that more study is needed, as the authors of the study say. But really, in science, isn’t more study always needed? Will we ever reach the end of understanding? Certainly not. And certainly not when it comes to the formation of planets, which is a pretty important thing to understand.

What Is The Electron Cloud Model?

The early 20th century was a very auspicious time for the sciences. In addition to Ernest Rutherford and Niels Bohr giving birth to the Standard Model of particle physics, it was also a period of breakthroughs in the field of quantum mechanics. Thanks to ongoing studies on the behavior of electrons, scientists began to propose theories whereby these elementary particles behaved in ways that defied classical, Newtonian physics.

One such example is the Electron Cloud Model proposed by Erwin Schrodinger. Thanks to this model, electrons were no longer depicted as particles moving around a central nucleus in a fixed orbit. Instead, Schrodinger proposed a model whereby scientists could only make educated guesses as to the positions of electrons. Hence, their locations could only be described as being part of a ‘cloud’ around the nucleus where the electrons are likely to be found.

Atomic Physics To The 20th Century:

The earliest known examples of atomic theory come from ancient Greece and India, where philosophers such as Democritus postulated that all matter was composed of tiny, indivisible and indestructible units. The term “atom” was coined in ancient Greece and gave rise to the school of thought known as “atomism”. However, this theory was more of a philosophical concept than a scientific one.

It was not until the 19th century that the theory of atoms became articulated as a scientific matter, with the first evidence-based experiments being conducted. For example, in the early 1800’s, English scientist John Dalton used the concept of the atom to explain why chemical elements reacted in certain observable and predictable ways. Through a series of experiments involving gases, Dalton went on to develop what is known as Dalton’s Atomic Theory.

This theory expanded on the laws of conversation of mass and definite proportions and came down to five premises: elements, in their purest state, consist of particles called atoms; atoms of a specific element are all the same, down to the very last atom; atoms of different elements can be told apart by their atomic weights; atoms of elements unite to form chemical compounds; atoms can neither be created or destroyed in chemical reaction, only the grouping ever changes.

Discovery Of The Electron:

By the late 19th century, scientists also began to theorize that the atom was made up of more than one fundamental unit. However, most scientists ventured that this unit would be the size of the smallest known atom – hydrogen. By the end of the 19th century, his would change drastically, thanks to research conducted by scientists like Sir Joseph John Thomson.

Through a series of experiments using cathode ray tubes (known as the Crookes’ Tube), Thomson observed that cathode rays could be deflected by electric and magnetic fields. He concluded that rather than being composed of light, they were made up of negatively charged particles that were 1ooo times smaller and 1800 times lighter than hydrogen.

This effectively disproved the notion that the hydrogen atom was the smallest unit of matter, and Thompson went further to suggest that atoms were divisible. To explain the overall charge of the atom, which consisted of both positive and negative charges, Thompson proposed a model whereby the negatively charged “corpuscles” were distributed in a uniform sea of positive charge – known as the Plum Pudding Model.

These corpuscles would later be named “electrons”, based on the theoretical particle predicted by Anglo-Irish physicist George Johnstone Stoney in 1874. And from this, the Plum Pudding Model was born, so named because it closely resembled the English desert that consists of plum cake and raisins. The concept was introduced to the world in the March 1904 edition of the UK’s Philosophical Magazine, to wide acclaim.

Development Of The Standard Model:

Subsequent experiments revealed a number of scientific problems with the Plum Pudding model. For starters, there was the problem of demonstrating that the atom possessed a uniform positive background charge, which came to be known as the “Thomson Problem”. Five years later, the model would be disproved by Hans Geiger and Ernest Marsden, who conducted a series of experiments using alpha particles and gold foil – aka. the “gold foil experiment.”

In this experiment, Geiger and Marsden measured the scattering pattern of the alpha particles with a fluorescent screen. If Thomson’s model were correct, the alpha particles would pass through the atomic structure of the foil unimpeded. However, they noted instead that while most shot straight through, some of them were scattered in various directions, with some going back in the direction of the source.

Geiger and Marsden concluded that the particles had encountered an electrostatic force far greater than that allowed for by Thomson’s model. Since alpha particles are just helium nuclei (which are positively charged) this implied that the positive charge in the atom was not widely dispersed, but concentrated in a tiny volume. In addition, the fact that those particles that were not deflected passed through unimpeded meant that these positive spaces were separated by vast gulfs of empty space.

By 1911, physicist Ernest Rutherford interpreted the Geiger-Marsden experiments and rejected Thomson’s model of the atom. Instead, he proposed a model where the atom consisted of mostly empty space, with all its positive charge concentrated in its center in a very tiny volume, that was surrounded by a cloud of electrons. This came to be known as the Rutherford Model of the atom.

Subsequent experiments by Antonius Van den Broek and Niels Bohr refined the model further. While Van den Broek suggested that the atomic number of an element is very similar to its nuclear charge, the latter proposed a Solar-System-like model of the atom, where a nucleus contains the atomic number of positive charge and is surrounded by an equal number of electrons in orbital shells (aka. the Bohr Model).

The Electron Cloud Model:

During the 1920s, Austrian physicist Erwin Schrodinger became fascinated by the theories Max Planck, Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Arnold Sommerfeld, and other physicists. During this time, he also became involved in the fields of atomic theory and spectra, researching at the University of Zurich and then the Friedrich Wilhelm University in Berlin (where he succeeded Planck in 1927).

In 1926, Schrödinger tackled the issue of wave functions and electrons in a series of papers. In addition to describing what would come to be known as the Schrodinger equation – a partial differential equation that describes how the quantum state of a quantum system changes with time – he also used mathematical equations to describe the likelihood of finding an electron in a certain position.

This became the basis of what would come to be known as the Electron Cloud (or quantum mechanical) Model, as well as the Schrodinger equation. Based on quantum theory, which states that all matter has properties associated with a wave function, the Electron Cloud Model differs from the Bohr Model in that it does not define the exact path of an electron.

Instead, it predicts the likely position of the location of the electron based on a function of probabilities. The probability function basically describes a cloud-like region where the electron is likely to be found, hence the name. Where the cloud is most dense, the probability of finding the electron is greatest; and where the electron is less likely to be, the cloud is less dense.

These dense regions are known as “electron orbitals”, since they are the most likely location where an orbiting electron will be found. Extending this “cloud” model to a 3-dimensional space, we see a barbell or flower-shaped atom (as in image at the top). Here, the branching out regions are the ones where we are most likely to find the electrons.

Thanks to Schrodinger’s work, scientists began to understand that in the realm of quantum mechanics, it was impossible to know the exact position and momentum of an electron at the same time. Regardless of what the observer knows initially about a particle, they can only predict its succeeding location or momentum in terms of probabilities.

At no given time will they be able to ascertain either one. In fact, the more they know about the momentum of a particle, the less they will know about its location, and vice versa. This is what is known today as the “Uncertainty Principle”.

Note that the orbitals mentioned in the previous paragraph are formed by a hydrogen atom (i.e. with just one electron). When dealing with atoms that have more electrons, the electron orbital regions spread out evenly into a spherical fuzzy ball. This is where the term ‘electron cloud’ is most appropriate.

This contribution was universally recognized as being one of the cost important contributions of the 20th century, and one which triggered a revolution in the fields of physics, quantum mechanics and indeed all the sciences. Thenceforth, scientists were no longer working in a universe characterized by absolutes of time and space, but in quantum uncertainties and time-space relativity!

We have written many interesting articles about atoms and atomic models here at Universe Today. Here’s What Is John Dalton’s Atomic Model?, What Is The Plum Pudding Model?, What Is Bohr’s Atomic Model?, Who Was Democritus?, and What Are The Parts Of An Atom?

For more information, be sure to check What Is Quantum Mechanics? from Live Science.

Astronomy Cast also has episode on the topic, like Episode 130: Radio Astronomy, Episode 138: Quantum Mechanics, and Episode 252: Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle

Supermassive Black Hole Found In The Cosmic Boonies

Astronomers have found a massive black hole in a place they never expected to find one. The hole comes in at 17 billion solar masses, which makes it the second largest ever found. (The largest is 21 billion solar masses.) And though its enormous mass is noteworthy, its location is even more intriguing.

Supermassive black holes are typically found at the centers of huge galaxies. Most galaxies have them, including our own Milky Way galaxy, where a comparatively puny 4 million solar mass black hole is located. Not only that, these gargantuan holes tend to be located in galaxies that are part of a large cluster of galaxies. Being surrounded by all that mass is a prerequisite for the formation of supermassive black holes. The largest one known, at 21 billion solar masses, is located in a very dense region of space called the Coma Cluster, where over 1,000 galaxies have been identified.

The largest supermassive holes also tend to be surrounded by bright companions, who have also grown large from the plentiful mass in their surroundings. (Of course, its not the black holes that are bright, but the quasars that surround them.) The long and the short of it is that supermassive black holes are usually found in galaxy clusters, and usually have other supermassive companions in the same region of space. They’re not found in isolation.

But this newly found black hole is in a rather sparse region of space. It’s in NGC 1600, an elliptical galaxy in the constellation Eridanus, 200 million light years from Earth. NGC 1600 is not a particularly large galaxy, and though it has been considered part of a larger group of galaxies, all its companions are much dimmer in comparison. So NGC 1600 is a rather small, isolated galaxy, with only a few dim companions.

There’s another way that supermassive holes can form. Instead of growing large over time, by feeding on the mass of their home galaxies and galaxy clusters, they can form when two galaxies merge, and two smaller holes become one. But even this requires that they be in a region where galaxies are plentiful, allowing for more collisions and mergers.

It may be possible that NGC is the result of a merger of two galaxies, or that it is two black holes that are currently merging. Or it could be that NGC 1600’s region of space was once extremely rich in gas, in the early days of the Universe, and that’s what gave rise to this ‘out of place’ supermassive black hole.

There is much to be learned about the conditions that give rise to these behemoth black holes. The MASSIVE study will combine several telescopes to survey and catalogue the largest galaxies and black holes. This should tell astronomers a lot about their distribution, and about the circumstances that allow them to exist. We might find even larger ones.

Venus Compared to Earth

Venus is often referred to as “Earth’s Twin” (or “sister planet”), and for good reason. Despite some rather glaring differences, not the least of which is their vastly different atmospheres, there are enough similarities between Earth and Venus that many scientists consider the two to be closely related. In short, they are believed to have been very similar early in their existence, but then evolved in different directions.

Earth and Venus are both terrestrial planets that are located within the Sun’s Habitable Zone (aka. “Goldilocks Zone”) and have similar sizes and compositions. Beyond that, however, they have little in common. Let’s go over all their characteristics, one by one, so we can in what ways they are different and what ways they are similar.

Watch the Moon Occult Vesta and Aldebaran This Weekend

So, did you miss yesterday’s occultation of Venus by the Moon? It was a tough one, to be sure, as the footpath for the event crossed Europe and Asia in the daytime. Watch that Moon, though, as it crosses back into the evening sky later this week, and occults (passes in front of) the bright star Aldebaran for eastern North America and, for Hawaii-based observers, actually covers the brightest of the asteroids, 4 Vesta. Continue reading “Watch the Moon Occult Vesta and Aldebaran This Weekend”