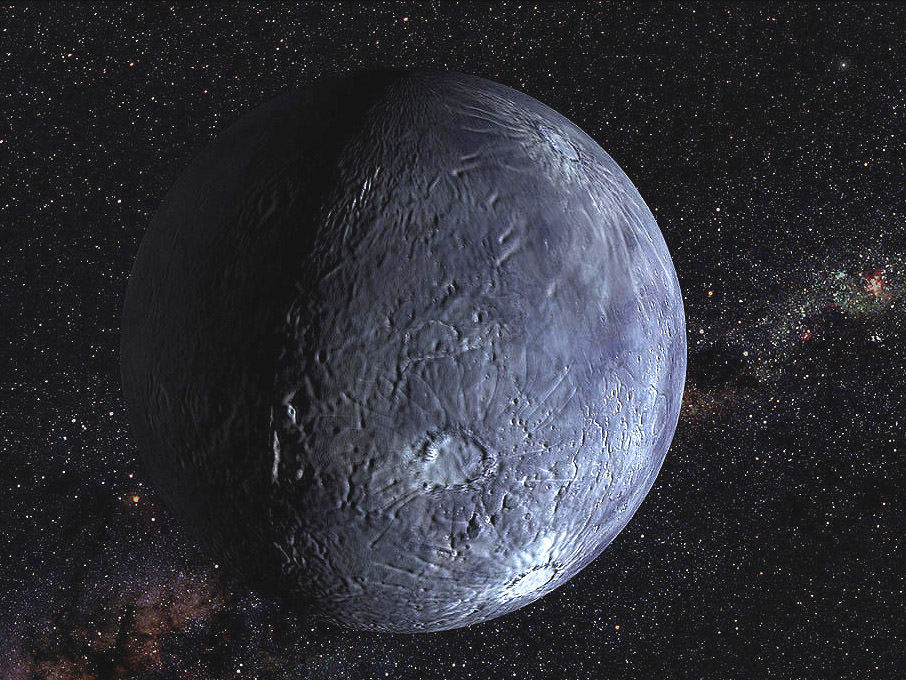

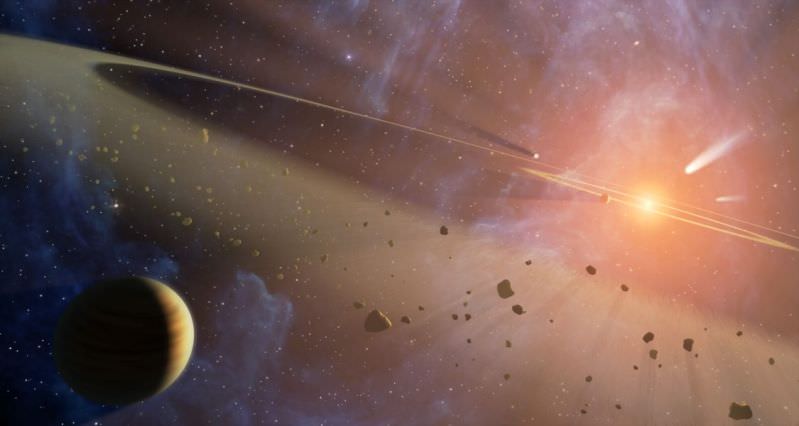

The vast Kuiper Belt, which orbits at the outer edge of our Solar System, has been the site of many exciting discoveries in the past decade or so. Otherwise known as the Trans-Neptunian region, small bodies have been discovered here that have confounded our notions of what constitutes a planet and thrown our entire classification system for a loop. Of these, the most famous (and controversial) discovery was undoubtedly Eris.

First observed in 2005 by Mike Brown and his team, the discovery of Eris overturned decades of astronomical conventions. But both before and since then, many other “dwarf planets“, “plutoids” and “Trans-Neptunian Objects” (TNOs) have been found that further illustrated the need for reclassification. This includes the Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) 5000 Quaoar (or just Quaoar), which was actually discovered three years before Eris.

Discovery and Naming:

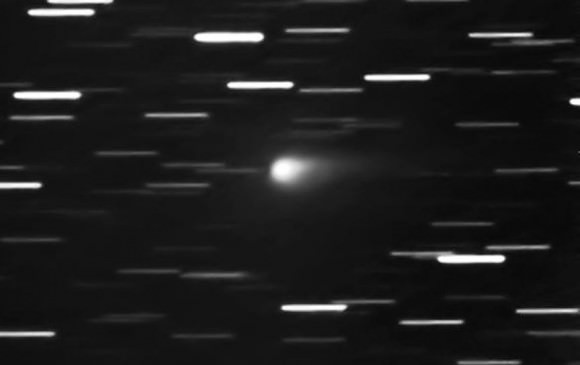

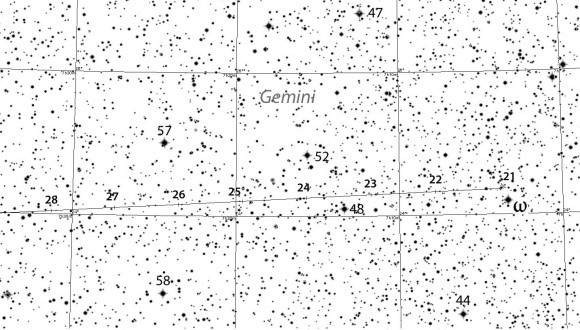

Quaoar was discovered on June 4th, 2002 by astronomers Chad Trujillo and Michael Brown of the California Institute of Technology, using images that were obtained with the Samuel Oschin Telescope at Palomar Observatory. The discovery was announced on October 7th, 2002, at a meeting of the American Astronomical Society. At the time, the object was designated as 2002 LM60, but would soon be renamed by Brown and Caltech his team.

Consistent with the IAU conventions for naming non-resonant Kuiper Belt Objects after creator deities, the object was given the name Quaoar after the Tongva creator god. The Tongva people (otherwise known as the Mission Indians) are native to the area around Los Angeles, where the discovery of Quaoar was made.

Size, Mass and Orbit:

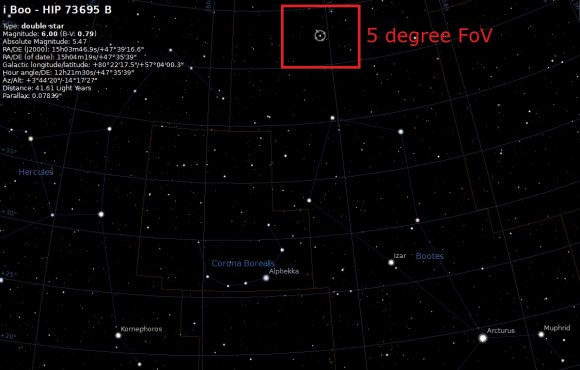

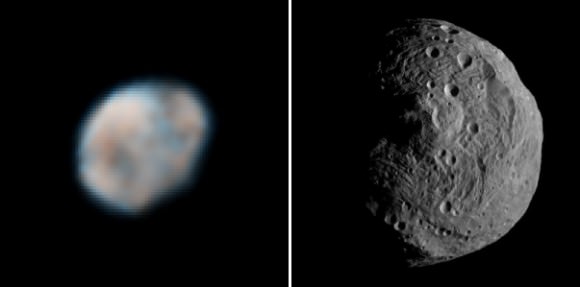

Given its distance, accurate measurements of Quaoar have been difficult to obtain. In 2004, Brown and Trujillo made direct measurements of the object with the Hubble Space Telescope and came up with an estimated diameter of 1260 ± 190 km.

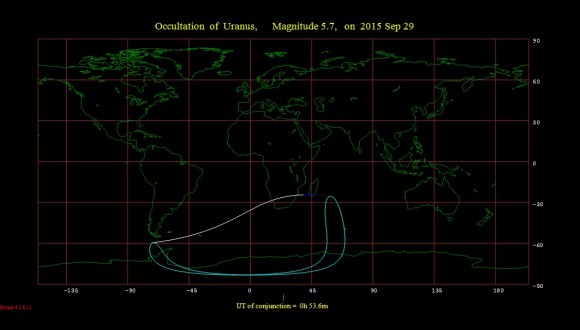

However, these estimates were subsequently revised downward in 2013 by teams using a stellar occultation, and with data obtained with the Herschel Observatory’s PACS instrument and the Spectral and Photometric Imaging Receiver (SPIRE) at the University of Lethbridge, Alberta.

Combining this information, estimates of its diameter were then changed to between 1110 ± 5 km and 1074±38 km. By these estimates, Quaoar was the largest object to be discovered in the Solar System since the discovery of Pluto. However, it would later be supplanted by the discoveries of Eris, Haumea, and Makemake.

In addition, new techniques and a greater knowledge of KBOs led scientists to conclude that the 2004 HST size estimate for Quaoar was approximately 40% too large, and that a more proper estimate would be about 900 km. Using a weighted average of the SST and corrected HST estimates, Quaoar, as of 2010, is now believed to be about 890±70 km in diameter.

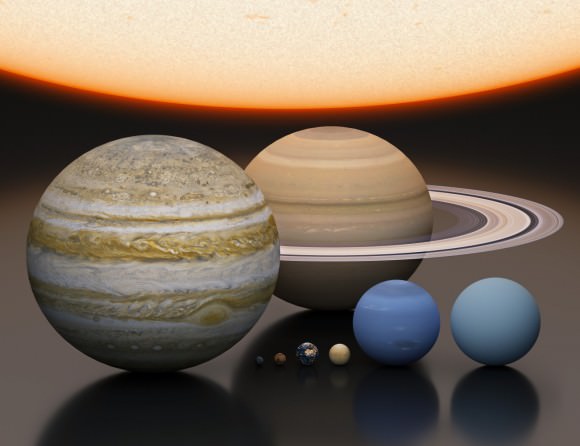

Given these dimensions, Quaoar is roughly one-twelfth the diameter of Earth, one third the diameter of the Moon, and half the size of Pluto. And with an estimated mass of 1.4 ± 0.1 × 1021 kg, Quaoar is about as massive as Pluto’s moon Charon, equivalent to 0.12 times the mass of Eris, and approximately 2.5 times as massive as Orcus.

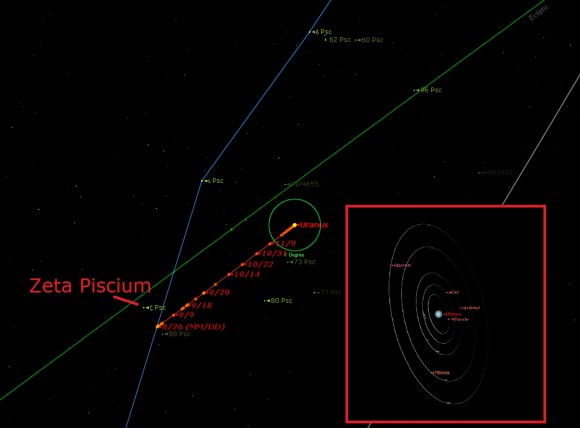

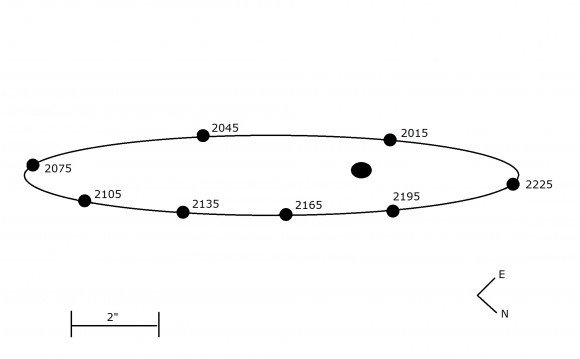

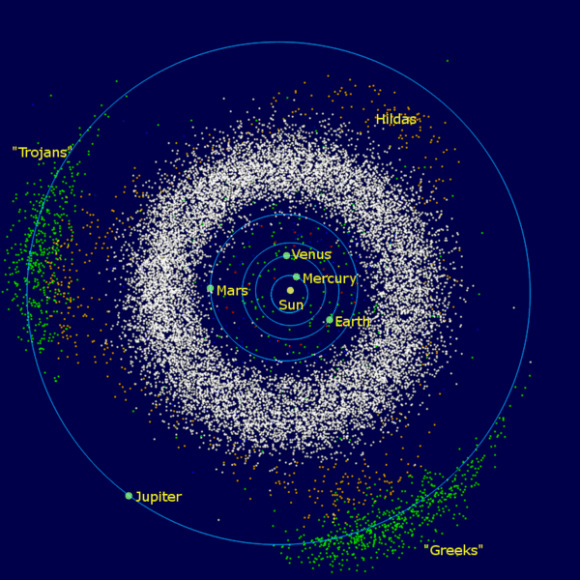

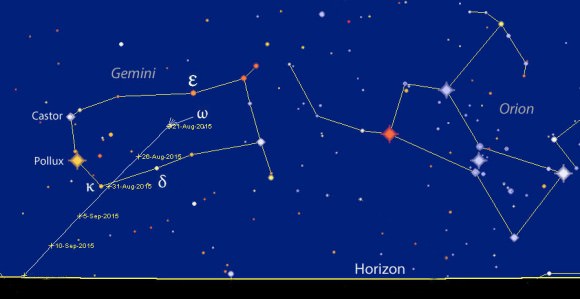

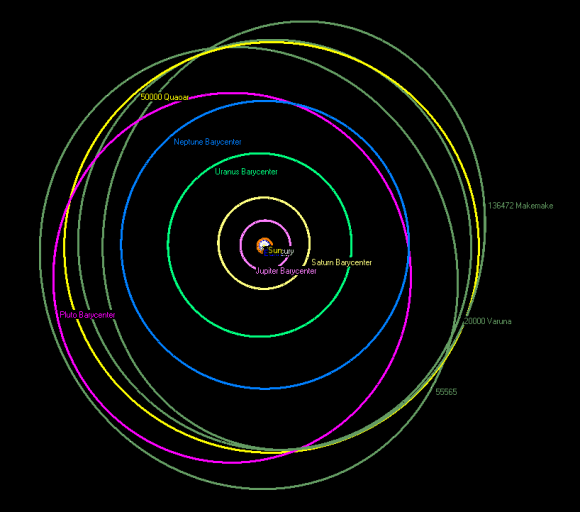

Quaoar orbit around the Sun varies slightly, ranging from 45.114 AU (6.75 x 109 km / 4.19 x 109 mi) at aphelion to 41.695 AU (6.24 x 10 km9/3.88 x 109 mi) at perihelion. Quaoar has an orbital period of 284.5 years, and a sidereal rotation period of about 17.68 hours.

Its orbit is also nearly circular and moderately inclined at approximately 8°, which is typical for the population of small classical KBOs, but exceptional among the large KBO. Pluto, Makemake, Haumea, Orcus, Varuna, and Salacia are all on highly inclined, more eccentric orbits.

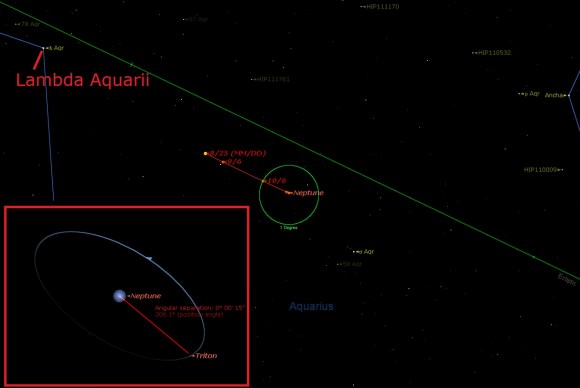

At 43 AU and with a near-circular orbit, Quaoar is not significantly perturbed by Neptune; unlike Pluto, which is in 2:3 orbital resonance with Neptune. As of 2008, Quaoar was only 14 AU from Pluto, which made it the closest large body to the Pluto–Charon system. By Kuiper Belt standards this is very close.

Composition:

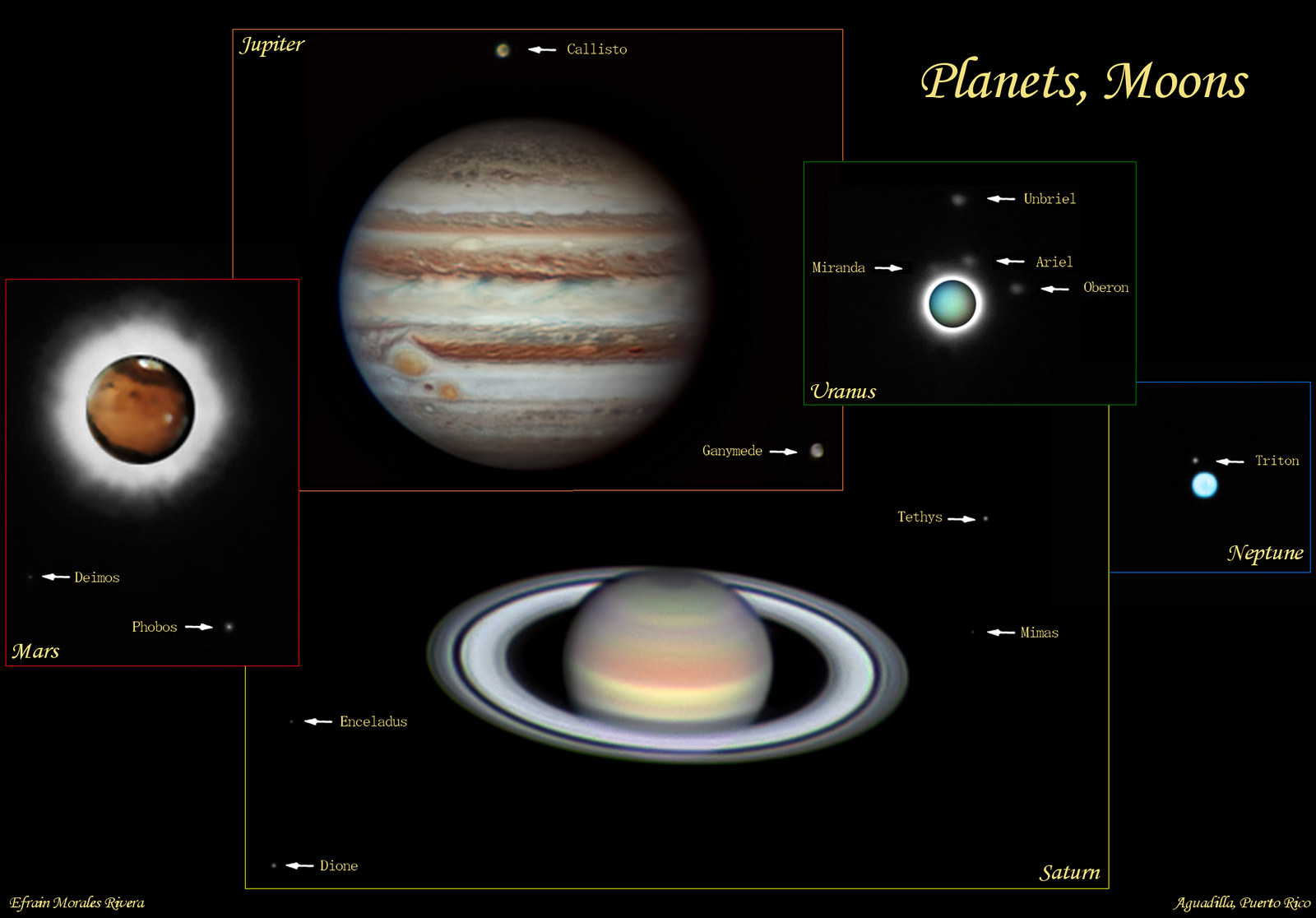

At the time of its discovery, not much was known about Kuiper belt objects. However, subsequent findings about this region have led scientists to conclude that the surface of Quaoar is likely to be highly similar to those of the icy satellites of Uranus and Neptune. This includes a low albedo, which could be as low as 0.1, which may be an indication that fresh ice has disappeared from its surface.

The surface is also moderately red, meaning that Quaoar is relatively more reflective in the red and near-infrared than in the blue. A 2006 model of internal heating via radioactive decay suggested that, unlike Orcus, Quaoar may not be capable of sustaining an internal ocean of liquid water at the mantle-core boundary.

Observations of Quaoar in the near infrared spectrum have indicated the presence of a small quantities of methane and ethane ice (about 5%). Scientists have also been surprised to find signs of crystalline ice on Quaoar, which is caused by sublimation and refreezing of water. This would indicate that the temperature rose to at least -160 °C (110 K or -260 °F) sometime in the last ten million years.

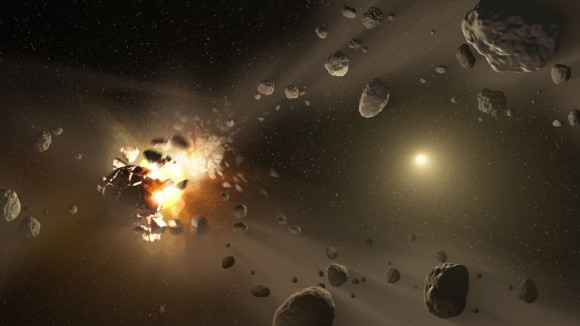

Speculation as to what could have caused Quaoar to heat up from its natural temperature of -220 °C (55 K or -360 °F) have led to theories ranging from a barrage of mini-meteors that could have raised the temperature, to the presence of cryovolcanism. The latter theory, which is the more widely accepted one, holds that cryovolcanism occurred as a result of the decay of radioactive elements within Quaoar’s core.

Some scientist believe that Quaoar was nearly twice its current size before an ancient collision with another object, possibly Pluto, stripped it of its outer mantle. If true, it would mean that Quaoar once had more ice on its surface, and possibly a liquid water ocean at the core-mantle boundary.

Moon:

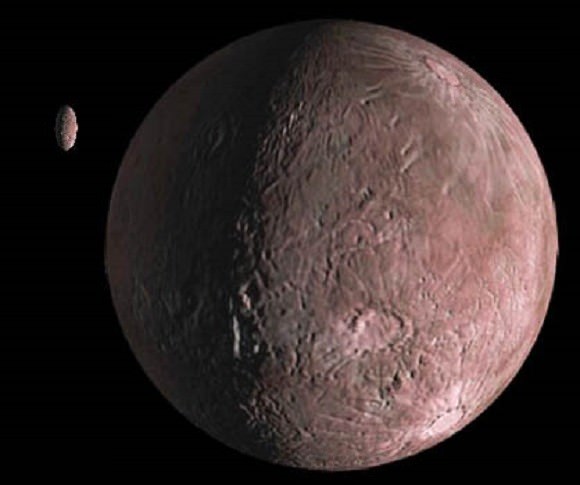

Quaoar has one known satellite, which was discovered on February 22nd, 2007. It orbits its primary at a distance of 14,500 km and has an orbital eccentricity of 0.14. Based on the assumption that the moon has the same albedo and density as Quaoar, the apparent magnitude of the moon indicates that it is 74 km in diameter and has 1/2000 the mass of Quaoar.

In terms of where it came from, Brown has suggested that it may be a remnant from a collision, which lost most of its mantle ice in the process. The choice for naming the moon was deferred to the Tongva people themselves, who selected the sky god Weymot, who is the son of Quaoar in Tongva mythology. The name became official on October 4th, 2009, with the publication of the Minor Planet Center’s latest issue.

Credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/R. Hurt (SSC-Caltech)

Classification:

According to the IAU, a dwarf planet is any celestial body that orbits a star, is massive enough to have become spherical under the power of its own gravity, but has not cleared its path of planetesimals, and is not the satellite of another object. Also, it must have enough mass to overcome its own compression and be in hydrostatic equilibrium.

Because Quaoar is a binary object, the mass of the system can be calculated from the orbit of the secondary. From this, Quaoar’s estimated density of 2.2 g/cm³ and its estimated diameter of 820 – 960 km suggest that it is large enough to be a dwarf planet.

This is based in part on estimates made by Mike Brown, who has claimed that rocky bodies around 900 km in diameter are sufficient to relax into hydrostatic equilibrium, whereas icy bodies can reach this state with diameters somewhere between 200 and 400 km.

In addition, Quaoar’s mass (which is believed to be greater than 1.6×1021 kg) is also greater than what the 2006 IAU draft definition of a planet claims is “usually” required for being in hydrostatic equilibrium (5×1020 kg, 800 km). Light-curve-amplitude analysis shows only small deviations, suggesting that Quaoar is indeed a spheroid with small albedo spots.

Therefore, while it is not currently classified as a dwarf planet, it is considered a viable candidate. In the coming years, it may go on to join the ranks of Pluto, Eris, Haumea and Makemake as being officially recognized as such by the IAU and other astronomical bodies.

Exploration:

So far, no missions have been planned to Quaoar. While some have advocated sending the New Horizons mission to visit Quaoar and/or Sedna now that it’s flyby of Pluto is complete, NASA has declared this to be impossible. Much like Sedna, Quaoar is too far from the trajectory of the spacecraft, but also insists that both KBOs will be high on the list of candidate targets for future missions to the outer Solar System.

It has further been calculated that a flyby mission to Quaoar could take 13.57 years, using a Jupiter gravity assist and based on the launch dates of December 25th, 2016, November 22nd, 2027, December 22nd, 2028, January 22nd, 2030, or December 20thm, 2040. During any of these launch windows, Quaoar would be at a distance of 41 to 43 AU from the Sun by the time the spacecraft arrived.

In the meantime, all we can do is wait, and continue to observe Quaoar and its fellow Kuiper Belt Objects from afar. In the coming years, a decision is also likely to be made about whether or not it will be included on the list of the Solar System’s acknowledge dwarf planets.

We have written many articles about Quaoar for Universe Today. Here’s an article about the discovery of Quaoar, and here’s an article about the Kuiper Belt.

If you’d like more info about Dwarf Planets, check out Solar System Exploration Guide on Dwarf Planets, and here’s a link to an article aboutthe dwarf planet, Ceres.

We’ve also recorded an entire episode of Astronomy Cast entitled Episode 194: Dwarf Planets and an interview with Mike Brown himself!

Sources: