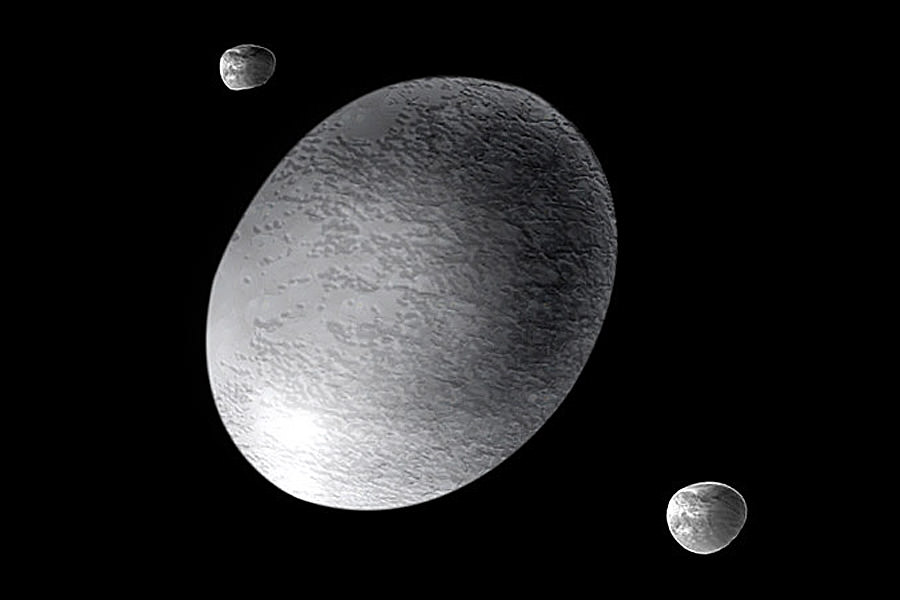

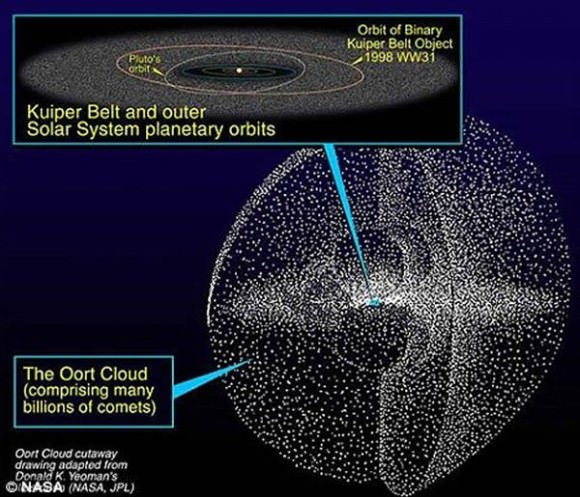

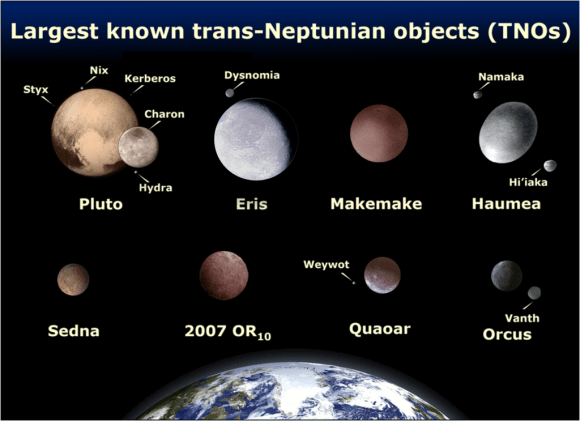

The Trans-Neptunian region has become a veritable treasure trove of discoveries in recent years. Since 2003, the dwarf planets and “plutoids” of Eris, Sedna, Makemake, Quaoar, and Orcus were all observed beyond the orbit of Pluto. And in between all of these, Haumea – that odd, oblong-shaped dwarf planet that has its own system of moons – was also discovered.

In addition to being the largest member of its particular family of Trans-Neptunian Objects (TNOs), Haumea is unique amongst known dwarf planets. This is due to its elongation, an unusually rapid rotation, two known moons, high density, and high albedo – all of which make Haumea something of an oddity when it comes to dwarf planets.

Discovery and Naming:

While bodies that are designated as dwarf planets tend to attract their share of controversy, dissension over Haumea began as soon as it was discovered. In fact, two teams claim credit for its discovery: Mike Brown and his team at Caltech and Jose Luis Ortiz Moreno and his team from the Instituto de Astrofísica de Andalucía at Sierra Nevada Observatory in Spain.

The former discovered Haumea in December of 2004 from images they had taken on May 6th, 2004 from the W.M. Keck Observatory. They published an online abstract about their discovery on July 20th, 2005, and announced their discovery at a conference in September of that year. Meanwhile, Ortiz and his team emailed the IAU Minor Planet Center of the discovery of Haumea on July 27th, 2005, claiming they had found it on images taken from March 7th to 10th, 2003.

The IAU announcement on September 17th, 2008, that Haumea had been accepted as a dwarf planet, did not mention a discoverer. The location of discovery was listed as the Sierra Nevada Observatory of the Spanish team, but the chosen name, Haumea, was proposed by the Caltech team.

The name Haumea comes from Hawaiian mythology, specifically from the goddess of fertility who is also the matron goddess of the island of Hawaii where the W. M. Keck Observatory is located. Hence, the name was not only consistent with IAU guidelines – that classical Kuiper Belt Objects (KBOs) be given names of mythological beings associated with creation – but was also an homage to the facility that made the discovery.

Ortiz’s team had proposed “Ataecina”, named for the ancient Iberian goddess of Spring; but not meet the IAU requirements since she is not a creation goddess, and hence was rejected. Until it was given a permanent name, the Caltech discovery team used the nickname “Santa” among themselves, because they had discovered Haumea on December 28th, 2004, just after Christmas.

Because the Spanish team had filed their claim with the Minor Planet Center first, Haumea was given the provisional designation 2003 EL61 (based on the date of the Spanish discovery image) on July 29th, 2005.

Size, Mass and Orbit:

Calculating Haumeau’s size, mass and density is somewhat complicated. Whereas it is large enough and bright enough for its albedo (and thus its size) to be measured, the calculations of its dimensions are made difficult by its rapid rotation. However, several ellipsoid-model calculations have been conducted using the Keck telescopes, the Spitzer Space Telescope, and the Herschel Space Telescope that have provided estimates.

The first calculations, conducted by Brown et al., provided the approximate dimensions of 2,000 x 1,500 x 1,000 km. Meanwhile, the Spitzer measurements gave it a diameter of 1050 – 1400 km, while subsequent light-curve analyses suggested an equivalent circular diameter of 1,450 km. In 2010 an analysis of measurements taken by Herschel Space Telescope together with the older Spitzer Telescope measurements yielded a new estimate of ~1300 km.

These independent size estimates overlap at an average geometric mean diameter of roughly 1,400 km. In essence, this means that Haumea is comparable in diameter to Pluto along its longest axis and about half that at its poles. It’s mass, meanwhile, is estimated to be approximately 4.0 ×1021 kg – one-third the mass of Pluto and 1/1400th that of Earth.

This makes Haumea one of the largest trans-Neptunian objects discovered, smaller than Eris, Pluto, probably Makemake, and possibly 2007 OR10, but larger than Sedna, Quaoar, and Orcus. Combined with estimates of its density, Haumea is massive enough to have achieved hydrostatic equilibrium. Although Haumea appears to be far from spherical, its ellipsoidal shape is thought to result from its rapid rotation.

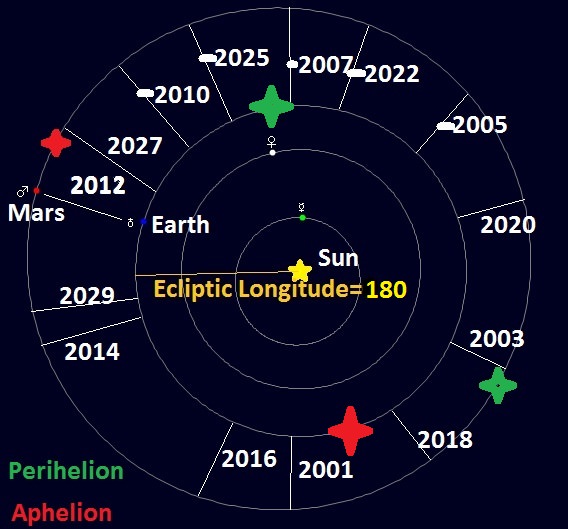

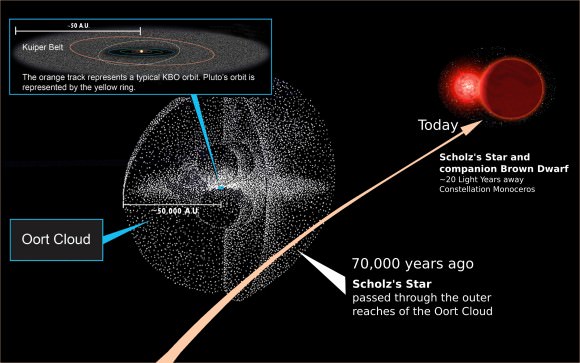

Haumea has a typical orbit for a classical KBO, with an eccentric orbit that takes it from 34.952 AU (5.23 billion km) at perihelion to 51.483 AU (7.7 billion km) at aphelion. Also consistent with other KBOs, it has an orbital period of 284 Earth years, an orbital inclination of 28°, and completes a sidereal rotation every 3.9 hours (0.163 Earth days).

Composition:

Much like its size, Haumea’s rotation and the amplitude of its light curve make judging its composition rather difficult. If its density were consistent with Pluto and other KBOs (2.0 g/cm³) then its rapid rotation would have elongated it to a greater extent than current estimates allow for. As such, Haumea’s density is believed to range between 2.6 – 3.3 g/cm³, which is comparable to Earth’s Moon (also 3.3 g/cm³).

Haumea’s possible density covers the values for silicate minerals such as olivine and pyroxene, which make up many of the rocky objects in the Solar System. This suggests that the bulk of Haumea is rock covered with a relatively thin layer of ice. It is possible that a thicker ice mantle that is more typical of Kuiper belt objects existed in the past, but was blasted off during the impact that formed the Haumean collisional family.

Haumea is as bright as snow, with an high albedo that is consistent with crystalline ice. Spectral modelling of the surface suggested that 66% to 80% of the Haumean surface appears to be pure crystalline water ice, with the possible presence of hydrogen cyanide or phyllosilicate clays. Inorganic cyanide salts such as copper potassium cyanide may also be present.

A large dark red area on Haumea’s bright white surface, possibly an impact feature, has also been observed which could indicate an area rich in minerals and organic (carbon-rich) compounds – or possibly a higher proportion of crystalline ice. Thus Haumea may have a mottled surface similar to that of Pluto.

Classification:

Haumea has been classified as a plutoid and dwarf planet residing beyond Neptune’s orbit. This classification means that it is presumed to be massive enough to have been rounded by its own gravity, but not to have cleared its neighborhood of similar objects.

Although Haumea appears to be far from spherical, its ellipsoidal shape is thought to result from its rapid rotation and not from a lack of sufficient gravity to overcome the compressive strength of its material. Haumea was initially listed as a classical Kuiper Belt Object in 2006 by the Minor Planet Center, but that has since been revised.

Moons:

Haumea has two known moons, which are named after the daughters of the Hawaiian goddess – Hi’iaka and Namaka. Both were discovered in 2005 by Brown’s team while conducting observations of Haumea at the W.M. Keck Observatory. Hi’iaka, which was initially nicknamed “Rudolph” by the Caltech team, was discovered January 26th, 2005.

It is the outer and – at roughly 310 km in diameter – the larger and brighter of the two, and orbits Haumea in a nearly circular path every 49 days. Infrared observations indicate that its surface is almost entirely covered by pure crystalline water ice. Because of this, Brown and his team have speculated that the moon is a fragment of Haumea that broke off during a collision.

Namaka, the smaller and innermost of the two, was discovered on June 30th, 2005, and nicknamed “Blitzen”. It is a tenth the mass of Hi‘iaka and orbits Haumea in 18 days in a highly elliptical orbit. Both moons circle Haumea is highly eccentric orbits. No estimates have been made yet as to their mass.

Exploration:

So far, no missions have been mounted to Haumea and none are currently planned. However, numerous scenarios have been calculated using hypothetical launch dates. For example, if a probe were launched on September 25th, 2025, a flyby mission could take place within 14.25 years, when Haumea would be 48.18 AU from the Sun. Based on a launch date of Nov. 1st, 2026, September 23rd, 2037, and October 29th, 2038, a flyby mission would take 16.45 years to get to Haumea.

So if the budget environment remains stable and scientists decide to make close-up observations of Haumea a priority, a flyby could be taking place no sooner than December of 2039. And with luck, we might learn more about this distant and odd little ball of rock and ice that stands out from its peers.

We have many interesting articles on Haumea, its surface features, the Kuiper Belt, Dwarf Planets, and Trans-Neptunian Objects here at Universe Today.

And here is What is the Kuiper Belt, KBOs, and What Has the Kuiper Belt Taught Us About The Solar System?

Sources: