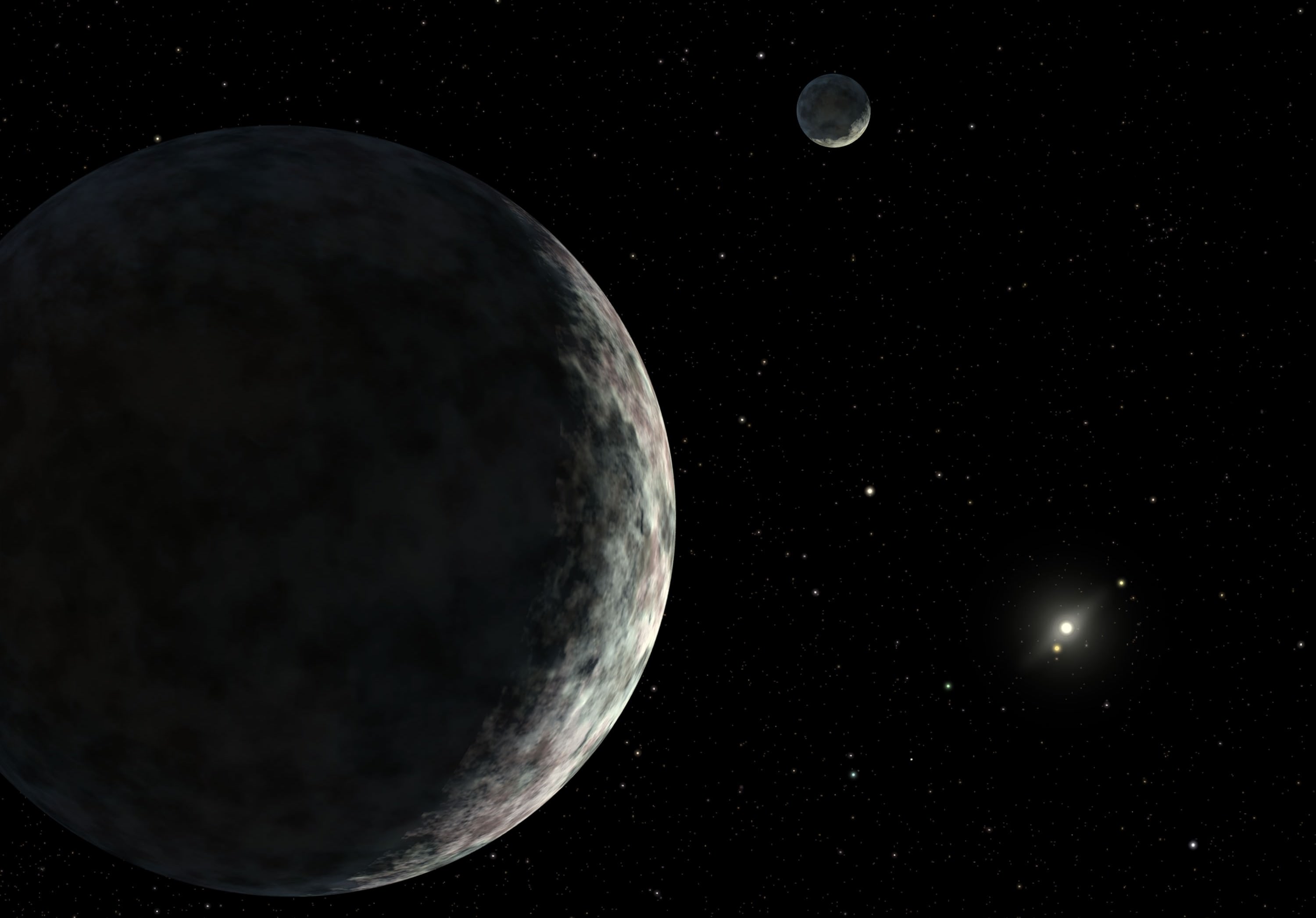

Ask a person what Dysnomia refers to, and they might venture that it’s a medical condition. In truth, they would be correct. But in addition to being a condition that affects the memory (where people have a hard time remembering words and names), it is also the only known moon of the distant dwarf planet Eris.

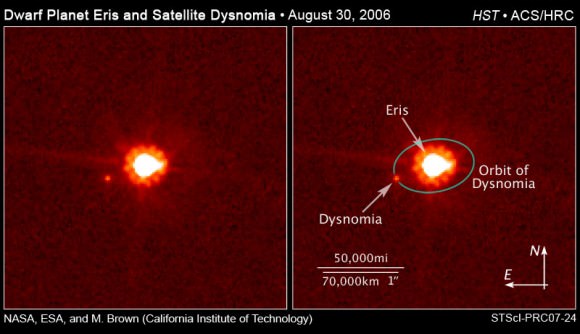

In fact, the same team that discovered Eris a decade ago – a discovery that threw our entire notion of what constitutes a planet into question – also discovered a moon circling it shortly thereafter. As the only satellite that circles one of the most distant objects in our Solar System, much of what we know about this ball of ice is still subject to debate.

Discovery and Naming:

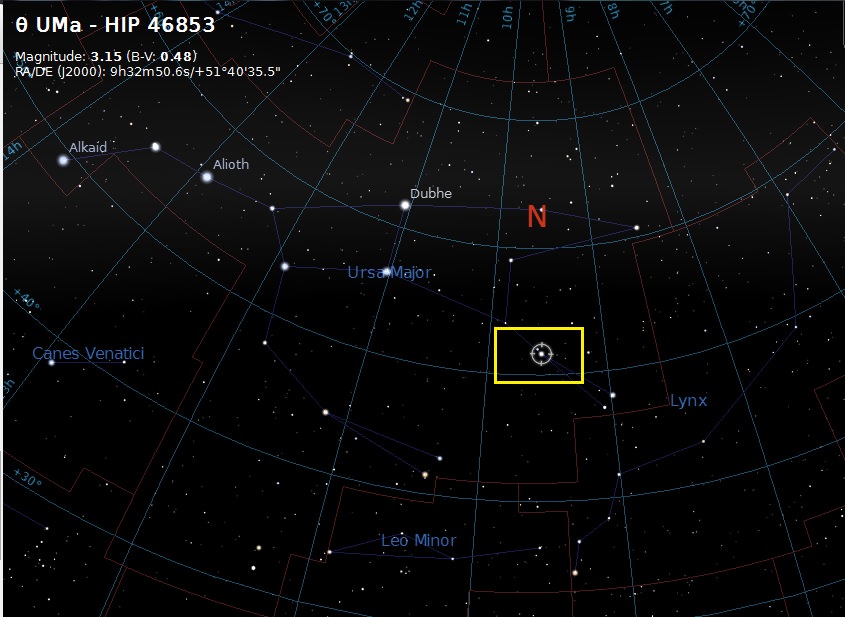

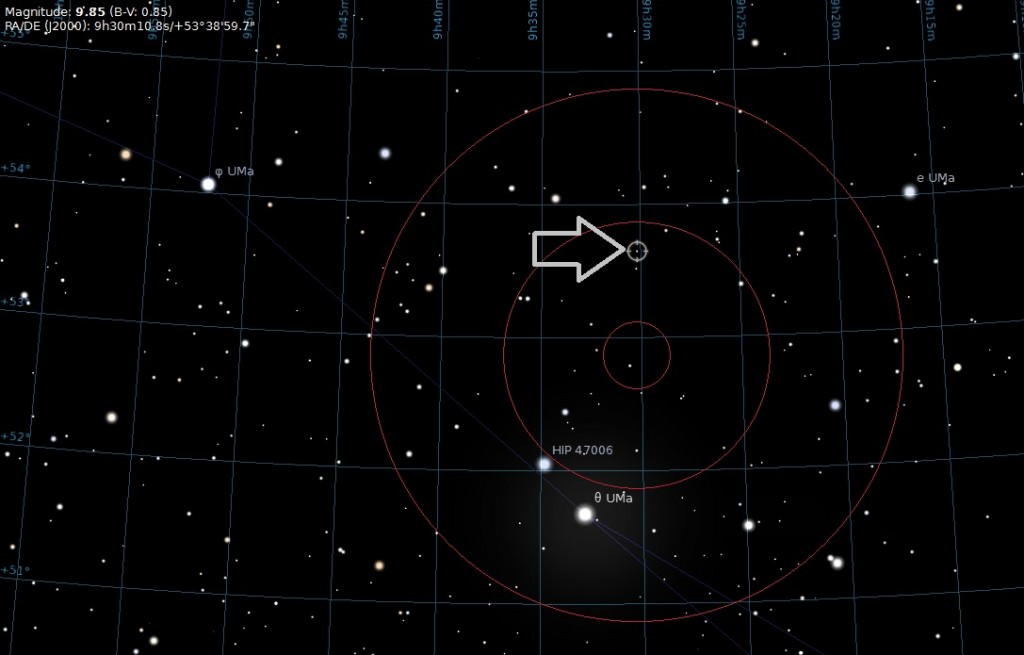

In January of 2005, astronomer Mike Brown and his team discovered Eris using the new laser guide star adaptive optics system at the W. M. Keck Observatory in Hawaii. By September, Brown and his team were conducting observations of the four brightest Kuiper Belt Objects – which at that point included Pluto, Makemake, Haumea, and Eris – and found indications of an object orbiting Eris.

Provisionally, this body was designated S/2005 1 (2003 UB³¹³). However, in keeping with the Xena nickname that his team was already using for Eris, Brown and his colleagues nicknamed the moon “Gabrielle” after Xena’s sidekick. Later, Brown selected the official name of Dysnomia for the moon, which seemed appropriate for a number of reasons.

For one, this name is derived from the daughter of the Greek god Eris – a daemon who represented the spirit of lawlessness – which was in keeping with the tradition of naming moons after lesser gods associated with the primary god. It also seemed appropriate since the “lawless” aspect called to mind actress Lucy Lawless, who portrayed Xena on television. However, it was not until the IAU’s resolution on what defined a planet – passed in August of 2006 – that the planet was officially designated as Dysnomia.

Size, Mass and Orbit:

The actual size of Dysnomia is subject to dispute, and estimates are based largely on the planet’s albedo relative to Eris. For example, the IAU and Johnston’s Asteroids with Satellites Database estimate that it is 4.43 magnitudes fainter than Eris and has an approximate diameter of between 350 and 490 km (217 – 304 miles)

However, Brown and his colleagues have stated that their observations indicate it to be 500 times fainter and between 100 and 250 km (62 – 155 miles) in diameter. Using the Herschel Space Observatory in 2012, Spanish astronomer Pablo Santo Sanz and his team determined that, provided Dysnomia has an albedo five times that of Eris, it is likely to be 685±50 km in diameter.

In 2007, Brown and his team also combined Keck and Hubble observations to determine the mass of Eris, and estimate the orbital parameters of the system. From their calculations, they determined that Dysnomia’s orbital period is approximately 15.77 days. These observations also indicated that Dysnomia has a circular orbit around Eris, with a radius of 37350±140 km. In addition to being a satellite of a dwarf planet, Dysnomia is also a Kuiper Belt Object (KBO) like Eris.

Composition and Origin:

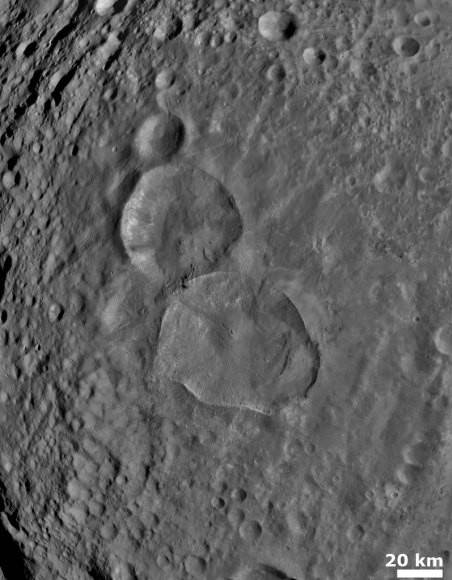

Currently, there is no direct evidence to indicate what Dysnomia is made of. However, based on observations made of other Kuiper Belt Objects, it is widely believed that Dysnomia is composed primarily of ice. This is based largely on infrared observations made of Haumea (2003 EL61), the fourth largest object in the Kuiper Belt (after Eris, Pluto and Makemake) which appears to be made entirely of frozen water.

Astronomers now know that three of the four brightest KBOs – Pluto, Eris and Haumea – have one or more satellites. Meanwhile, of the fainter members, only about 10% are known to have satellites. This is believed to imply that collisions between large KBOs have been frequent in the past. Impacts between bodies of the order of 1000 km across would throw off large amounts of material that would coalesce into a moon.

This could mean that Dysnomia was the result of a collision between Eris and a large KBO. After the impact, the icy material and other trace elements that made up the object would have evaporated and been ejected into orbit around Eris, where it then re-accumulated to form Dysnomia. A similar mechanism is believed to have led to the formation of the Moon when Earth was struck by a giant impactor early in the history of the Solar System.

Since its discovery, Eris has lived up to its namesake by stirring things up. However, it has also helped astronomers to learn many things about this distant region of the Solar System. As already mentioned, astronomers have used Dysnomia to estimate the mass of Eris, which in turn helped them to compare it to Pluto.

While astronomers already knew that Eris was bigger than Pluto, but they did not know whether it was more massive. This they did by measuring the distance between Dysnomia and how long it takes to orbit Eris. Using this method, astronomers were able to discover that Eris is 27% more massive than Pluto is.

With this knowledge in hand, the IAU then realized that either Eris needed to be classified as a planet, or that the term “planet” itself needed to be refined. Ergo, one could make that case that it was the discovery of Dysnomia more than Eris that led to Pluto no longer being designated a planet.

Universe Today has articles on Xena named Eris and The Dwarf Planet Eris. For more information, check out Dysnomia and dwarf planet outweighs Pluto.

Astronomy Cast has an episode on Pluto’s planetary identity crisis.

Sources: