What if someone were to tell you that there’s a region in the world where roughly 90% of the world’s earthquakes occur. What if they were to tell you that this region is also home to over 75% of the world’s active and dormant volcanoes, and all but 3 of the world’s 25 largest eruptions in the last 11,700 years took place here.

Chances are, you’d think twice about buying real-estate there. But strangely enough, hundreds of millions of people live in this area, and some of the most densely-packed cities in the world have been built atop its shaky faults. We are talking about the Pacific Ring of Fire, a geologically and volcanically active region that stretches from one side of the Pacific to the other.

Definition:

Also known as the circum-Pacific belt, the “Ring of Fire” is a 40,000 km (25,000 mile) horseshoe-shaped basin that is associated with a nearly continuous series of oceanic trenches, volcanic arcs, and volcanic belts and/or plate movements. This ring accounts for 452 volcanoes (active and dormant), stretching from the southern tip of South America, up along the coast of North America, across the Bering Strait, down through Japan, and into New Zealand – with several active and dormant volcanoes in Antarctica closing the ring.

Tectonic Activity:

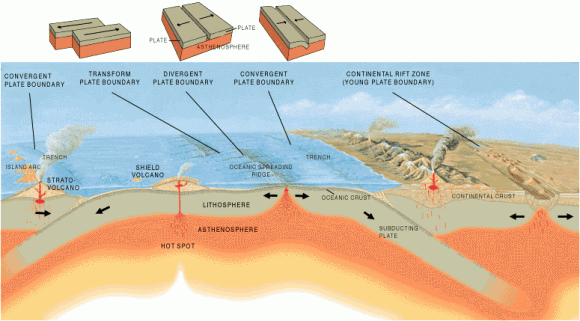

The Ring of Fire is the direct result of plate tectonics and the movement and collisions of lithospheric plates. These plates, which constitute the outer layer of the planet, are constantly in motion atop the mantle. Sometimes they collide, pull apart, or slide alongside each other; resulting in convergent boundaries, divergent boundaries, and transform boundaries.

In the case of the former, subduction zones are often the result, where the heavier plate slips under the lighter plate – forming a deep trench. This subduction changes the dense mantle into buoyant magma, which rises through the crust to the Earth’s surface. Over millions of years, this rising magma creates a series of active volcanoes known as a volcanic arc.

These ocean trenches and volcanic arcs run parallel to one another. For instance, the Aleutian Islands in the U.S. state of Alaska run parallel to the Aleutian Trench. Both geographic features continue to form as the Pacific Plate subducts beneath the North American Plate. Meanwhile, the Andes Mountains of South America run parallel to the Peru-Chile Trench, created as the Nazca Plate subducts beneath the South American Plate.

In the case of divergent boundaries, these are formed when tectonic plates pull apart, forming rift valleys on the seafloor. When this happens, magma wells up in the rift as the old crust pulls itself in opposite directions, where it is cooled by seawater to form new crust. This upward movement and eventual cooling of this magma has created high ridges on the ocean floor over millions of years.

The East Pacific Rise is a site of major seafloor spreading in the Ring of Fire, located on the divergent boundary of the Pacific Plate and the Cocos Plate (west of Central America), the Nazca Plate (west of South America), and the Antarctic Plate. The largest known group of volcanoes on Earth is found underwater along the portion of the East Pacific Rise between the coasts of northern Chile and southern Peru.

A transform boundary is formed when tectonic plates slide horizontally and parts get stuck at points of contact. Stress builds in these areas as the rest of the plates continue to move, which causes the rock to break or slip, suddenly lurching the plates forward and causing earthquakes. These areas of breakage or slippage are called faults, and the majority of Earth’s faults can be found along transform boundaries in the Ring of Fire.

The San Andreas Fault, stretching along the central west coast of North America, is one of the most active faults on the Ring of Fire. It lies on the transform boundary between the North American Plate, which is moving south, and the Pacific Plate, which is moving north. Measuring about 1,287 kilometers (800 miles) long and 16 kilometers (10 miles) deep, the fault cuts through the western part of the U.S. state of California.

Plate Boundaries:

The eastern section of the Ring of Fire is the result of the Nazca Plate and the Cocos Plate being subducted beneath the westward moving South American Plate. Meanwhile, the Cocos Plate is being subducted beneath the Caribbean Plate, in Central America. A portion of the Pacific Plate along with the small Juan de Fuca Plate are being subducted beneath the North American Plate.

Along the northern portion, the northwestward-moving Pacific plate is being subducted beneath the Aleutian Islands arc. Farther west, the Pacific plate is being subducted along the Kamchatka Peninsula arcs on south past Japan.

The southern portion is more complex, with a number of smaller tectonic plates in collision with the Pacific plate from the Mariana Islands, the Philippines, Bougainville, Tonga, and New Zealand. This portion excludes Australia, since it lies in the center of its tectonic plate.

Indonesia lies between the Ring of Fire along the northeastern islands adjacent to and including New Guinea and the Alpide belt along the south and west from Sumatra, Java, Bali, Flores, and Timor. The famous and very active San Andreas Fault zone of California is a transform fault which offsets a portion of the East Pacific Rise under southwestern United States and Mexico.

Volcanic Activity:

Most of the active volcanoes on The Ring of Fire are found on its western edge, from the Kamchatka Peninsula in Russia, through the islands of Japan and Southeast Asia, to New Zealand. Mount Ruapehu in New Zealand is one of the more active volcanoes in the Ring of Fire, with yearly minor eruptions, and major eruptions occurring about every 50 years.

Krakatau, perhaps better known as Krakatoa, is an island volcano in Indonesia. Krakatoa erupts less often than Mount Ruapehu, but much more spectacularly. Beneath Krakatoa, the denser Australian Plate is being subducted beneath the Eurasian Plate. An infamous eruption in 1883 destroyed the entire island, sending volcanic gas, volcanic ash, and rocks as high as 80 kilometers (50 miles) in the air. A new island volcano, Anak Krakatau, has been forming with minor eruptions ever since.

Mount Fuji, Japan’s tallest and most famous mountain, is an active volcano in the Ring of Fire. Mount Fuji last erupted in 1707, but recent earthquake activity in eastern Japan may have put the volcano in a “critical state.” Mount Fuji sits at a “triple junction,” where three tectonic plates (the Amur Plate, Okhotsk Plate, and Philippine Plate) interact.

The Ring of Fire’s eastern half also has a number of active volcanic areas, including the Aleutian Islands, the Cascade Mountains in the western U.S., the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, and the Andes Mountains. Mount St. Helens, in the U.S. state of Washington, is an active volcano in the Cascade Mountains.

Below Mount St. Helens, both the Juan de Fuca and Pacific plates are being subducted beneath the North American Plate. Its historic 1980 eruption lasted 9 hours and covered 11 U.S. states with tons of volcanic ash. The eruption caused the deaths of 57 people, over a billion dollars in property damage, and reduced hundreds of square miles to wasteland.

Popocatépetl is one of the most active and dangerous volcanoes in the Ring of Fire, with 15 recorded eruptions since 1519. The volcano lies on the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt, which is the result of the small Cocos Plate subducting beneath the North American Plate. Located close to the urban areas of Mexico City and Puebla, Popocatépetl poses a risk to the more than 20 million people that live close enough to be threatened by a destructive eruption.

Earthquakes:

Scientists have known for some time that the majority of the seismic activity occurs along plate boundaries. Hence why roughly 90% of the world’s earthquakes – which is estimated to be around 500,000 a year, one-fifth of which are detectable – occur around the Pacific Rim, where multiple plate boundaries exist.

As a result, earthquakes are a regular occurrence in places like Japan, Indonesia and New Zealand in Asia and the South Pacific; Alaska, British Columbia, California and Mexico in North America; and El Salvador, Guatemala, Peru and Chile in Central and South America. Where fault lines run beneath the ocean, larger earthquakes in these regions also trigger tsunamis.

The most well-known tsumanis to take place in the Ring of Fire include the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami. This was the most devastating tsunami of its kind in modern times, killing around 230,000 people and laying waste to communities throughout Indonesia, Thailand, and Southern Asia.

In 2010, an earthquake triggered a tsunami which caused 4334 confirmed deaths and devastating several coastal towns in south-central Chile, including the port at Talcahuano. The earthquake also generated a blackout that affected 93 percent of the Chilean population.

In 2011, an earthquake off the Pacific coast of Tohoku led to a tsunami that struck Japan and led to 5,891 deaths, 6,152 injuries, and 2,584 people to be declared missing across twenty prefectures. The tsunami also caused meltdowns at three reactors in the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant complex.

The Ring of Fire is a crucial region for many reasons. It serves as one of the main boundary regions for the tectonic plates of over half of the globe. It also affects the lives of millions if not billions of people who live in these regions. For many of the people who live in the Pacific Ring of Fire, the reality of a volcanic eruption or earthquake is commonplace and a challenge they have come to deal with over time.

At the same time, the volcanic activity has also provided many valuable resources, such as rich farmland and the possibility of tapping geothermal activity for heating and electricity. As always, nature gives with one hand and takes with the other!

If you have enjoyed this article there are several others on Universe Today that you will find interesting. Here is one called 10 Interesting Facts About Volcanoes. There is also a great article about plate tectonics.

You can also find some good resources online. There is a companion site for the PBS program Savage Earth that talks about the Ring of Fire. You can also check out the USGS site to see a detailed map of the Pacific Ring of Fire and more detailed information about plate tectonics.

You can also listen to Astronomy Cast. Episode 141 talks about volcanoes.