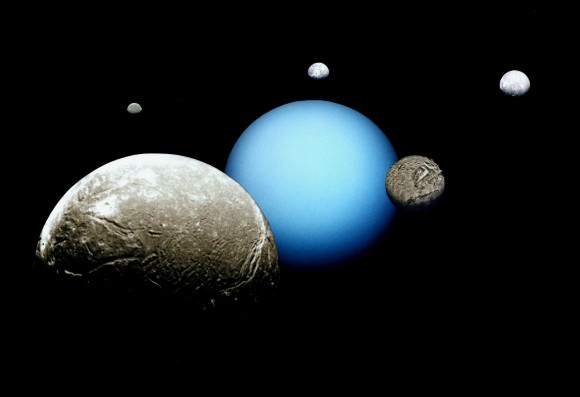

Thanks to the Voyager missions, which passed through the outer Solar system in the late 1970s and early 1980s, scientists were able to get the first close look at Uranus and its system of moons. Like all of the Solar Systems’ gas giants, Uranus has many fascinating satellites. In fact, astronomers can now account for 27 moons in orbit around the teal-colored giant.

Of these, none are greater in size, mass, or surface area than Titania, which was appropriately named. As one of the first moon’s to be discovered around Uranus, this heavily cratered and scarred moon takes it name from the fictional Queen of the Fairies in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

Discovery and Naming:

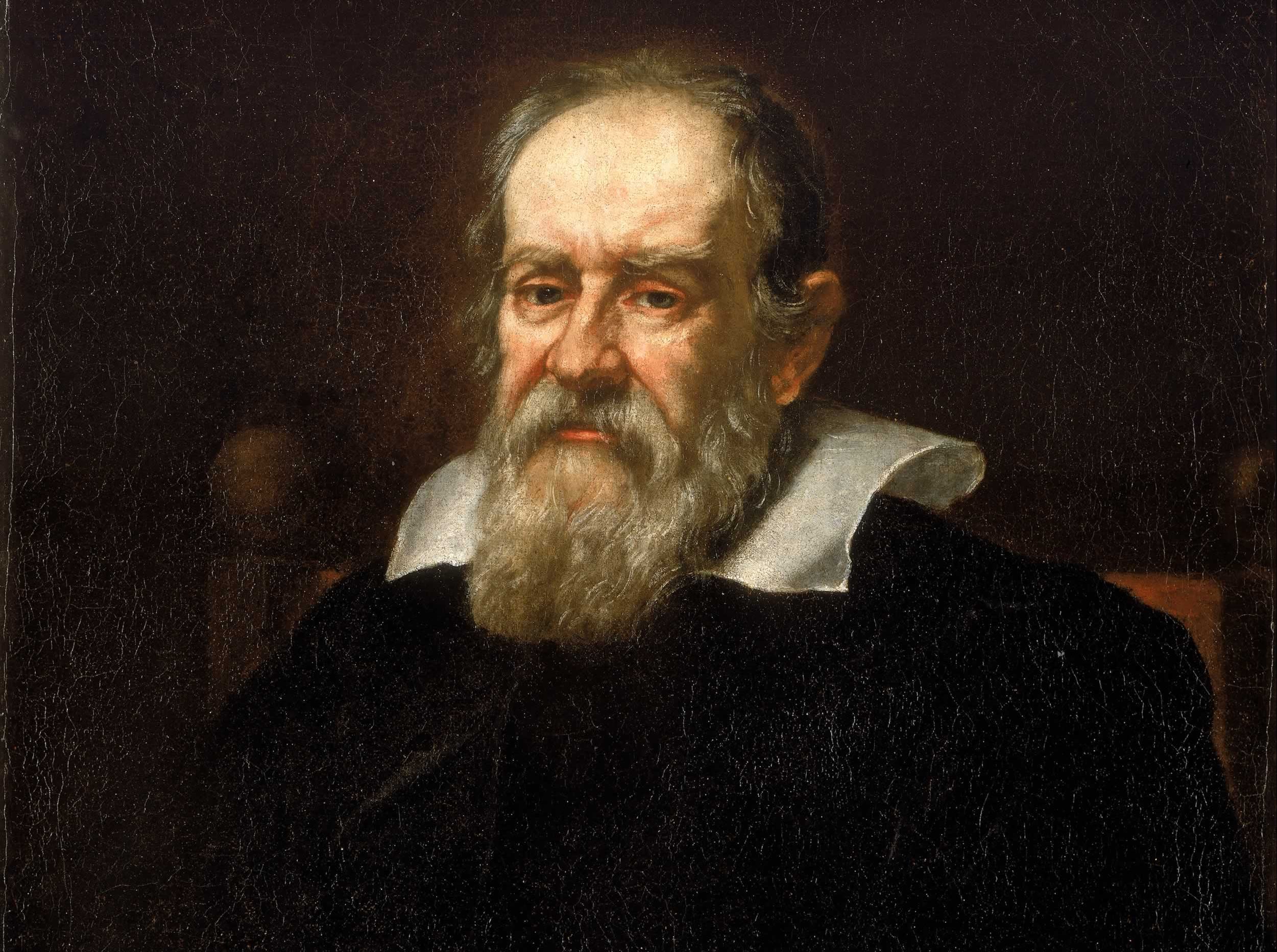

Titania was discovered by William Herschel on January 11th, 1787, the English astronomer who had discovered Uranus in 1781. The discovery was also made on the same day that he discovered Oberon, Uranus’ second-largest moon. Although Herschel reported observing four other moons at the time, the Royal Astronomical Society would later determine that this claim was spurious.

It would be almost five decades after Titania and Oberon was discovered that an astronomer other than Herschel would observe them. In addition, Titania would be referred to as “the first satellite of Uranus” for many years – or by the designation Uranus I, which was given to it by William Lassell in 1848.

By 1851, Lassell began to number all four known satellites in order of their distance from the planet by Roman numerals, at which point Titania’s designation became Uranus III. By 1852, Herschel’s son John, and at the behest of Lassell himself, suggested the moon’s name be changed to Titania, the Queen of the Fairies in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. This was consistent with all of Uranus’ satellites, which were given names from the works of William Shakespeare and Alexander Pope.

Size, Mass and Orbit:

With a diameter of 1,578 kilometers, a surface area of 7,820,000 km² and a mass of 3.527±0.09 × 1021 kg, Titania is the largest of Uranus’ moons and the eighth largest moon in the Solar System. At a distance of about 436,000 km (271,000 mi), Titania is also the second farthest from the planet of the five major moons.

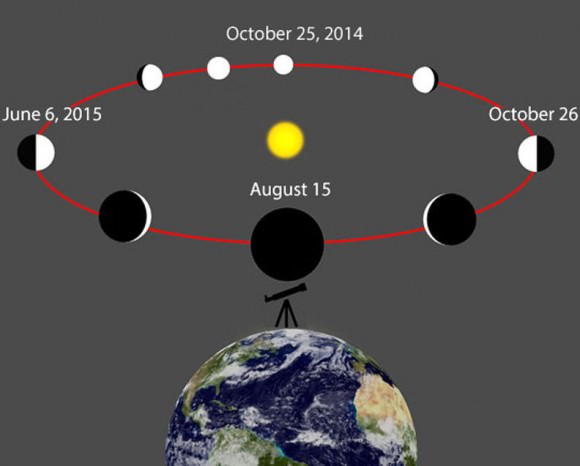

Titania’s moon also has a small eccentricity and is inclined very little relative to the equator of Uranus. It’s orbital period, which is 8.7 days, is also coincident with it’s rotational period. This means that Titania is a synchronous (or tidally-locked) satellite, with one face always pointing towards Uranus at all times.

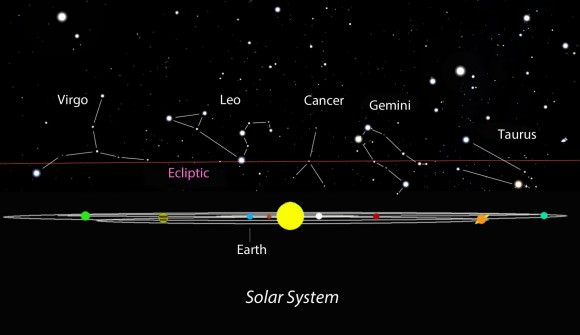

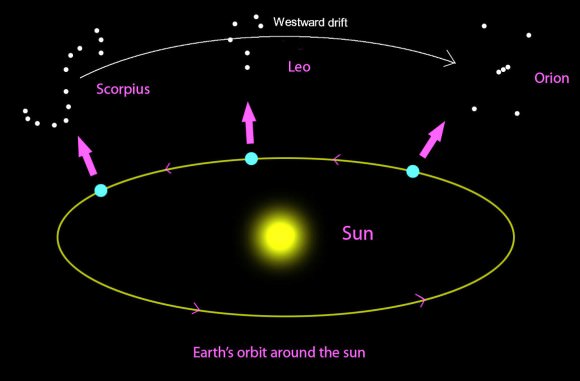

Because Uranus orbits the Sun on its side, and its moons orbit the planet’s equatorial plane, they are all subject to an extreme seasonal cycle, where the northern and southern poles experience 42 years of either complete darkness or complete sunlight.

Composition:

Scientists believe Titania is composed of equal parts rock (which may include carbonaceous materials and organic compounds) and ice. This is supported by examinations that indicate that Titania has an unusually high-density for a Uranian satellite (1.71 g/cm³). The presence of water ice is supported by infrared spectroscopic observations made in 2001–2005, which have revealed crystalline water ice on the surface of the moon.

It is also believed that Titania is differentiated into a rocky core surrounded by an icy mantle. If true, this would mean that the core’s radius is approx. 520 km (320 mi), which would mean the core accounts for 66% of the radius of the moon, and 58% of its mass.

As with Uranus’ other major moons, the current state of the icy mantle is unknown. However, if the ice contains enough ammonia or other antifreeze, Titania may have a liquid ocean layer at the core-mantle boundary. The thickness of this ocean, if it exists, is up to 50 km (31 mi) and its temperature is around 190 K.

Naturally, it is unlikely that such an ocean could support life. But assuming this ocean supports hydrothermal vents on its floor, it is possible life could exist in small patches close to the core. However, the internal structure of Oberon depends heavily on its thermal history, which is poorly known at present.

Voyager 2:

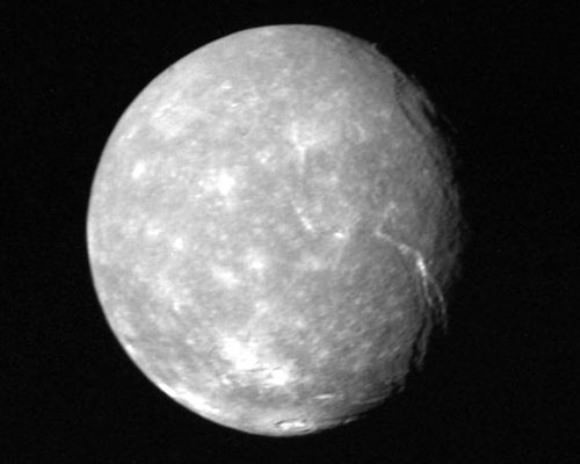

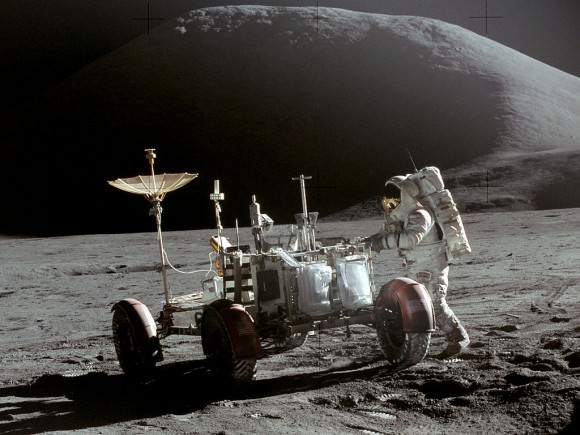

The only direct observations made of Titania were conducted by the Voyager 2 space probe, which photographed the moon during its flyby of Uranus in January 1986. These images covered about 40% of the surface, but only 24% was photographed with the precision required for geological mapping.

Voyager’s flyby of Titania coincided with the southern hemisphere’s summer solstice, when nearly the entire northern hemisphere was unilluminated. As with the other major moon’s of Uranus, this prevented the surface from being mapped in any detail. No other spacecraft has visited the Uranian system or Titania before or since, and no mission is planned in the foreseeable future.

Interesting Facts:

Titania is intermediate in terms of brightness, occupying a middle spot between the dark moons of Oberon and Umbriel and the bright moons of Ariel and Miranda. It’s surface is generally red in color (less so than Oberon), except where fresh impact have taken place, which have left the surface blue in color. The surface of Titania is less heavily cratered than the surface of either Oberon or Umbriel, suggesting that its surface is much younger.

Like all of Uranus’ major moons, it’s geology is influenced by a combination of impact craters and endogenic resurfacing. Whereas the former acted over the moon’s entire history and influenced all its surfaces, the latter processes were mainly active following the moon’s formation and resulted in a smoothing out of its features – hence the low number of present-day impact craters.

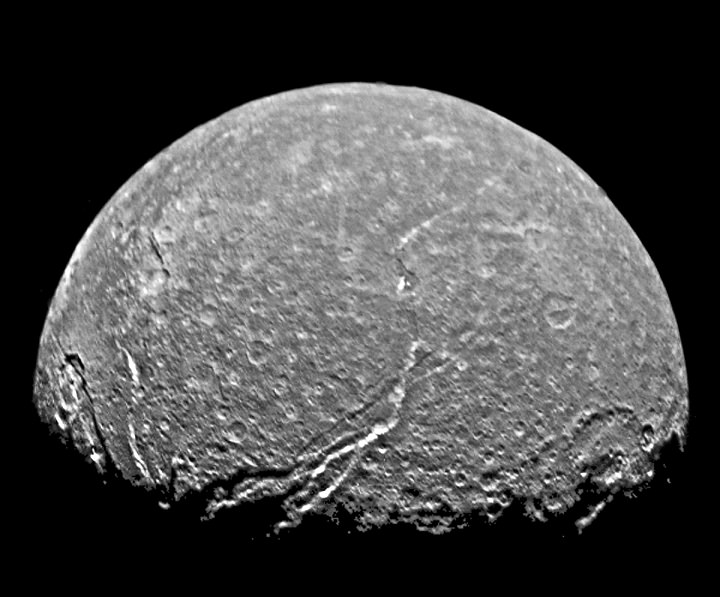

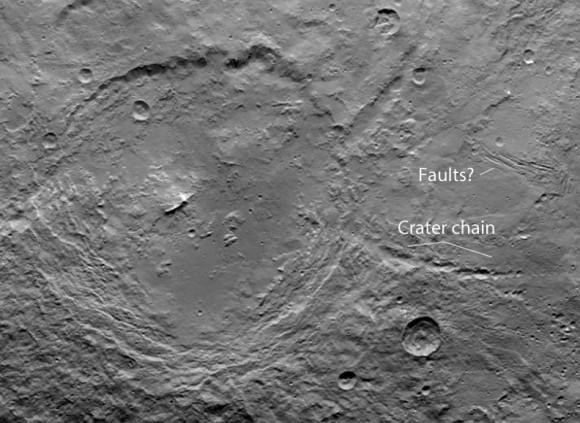

Overall, scientists have recognized three classes of geological feature on Titania. These include craters, faults (or scarps) and what are known as grabens (sometimes called canyons). Titania’s craters range in diameter from a few kilometers to 326 kilometers – in the case of the largest known crater, Gertrude. Titania’s surface is also intersected by a system of enormous faults (scarps); and in some places, two parallel scarps mark depressions in the satellite’s crust, forming grabens (aka. canyons).

The grabens on Titania range in diameter from 20 to 50 kilometers (12–31 mi) and in a relief (i.e. depth) from 2 to 5 km. The most prominent graben on Titania is the Messina Chasma, which runs for about 1,500 kilometers (930 mi) from the equator almost to the south pole. The grabens are probably the youngest geological features on Titania, since they cut through all craters and even the smooth plains.

Like Oberon, the surface features on Titania have been named after characters in works by Shakespeare, with all of the physical features are named after female characters. For instance, the crater Gertrude is named after Hamlet’s mother, while other craters – Ursula, Jessica, and Imogen – are named after characters from Much Ado About Nothing, The Merchant of Venice, and Cymebline, respectively.

Interestingly, the presence of carbon dioxide on the surface suggests that Titania may also have a tenuous seasonal atmosphere of CO², much like that of the Jovian moon Callisto. Other gases, like nitrogen or methane, are unlikely to be present, because Titania’s weak gravity could not prevent them from escaping into space.

Like all of Uranus’ moons, much remains to be discovered about this most-massive of her satellites. In the coming years, one can only hope that NASA, the ESA, or other space agencies decide that another Voyager-like mission is need to the outer Solar System. Until such time, Uranus and the many moons that orbit it will continue to keep secrets from us.

We have written many articles on Titania here at Universe Today. Here’s How Many Moons Does Uranus Have?, Uranus’ Moon Oberon and Uranus’ Moon Umbriel.

For more information, check out Nine Planets page on Titania and NASA’s Solar System Exploration page on Titania.

Astronomy Cast has an episode on the subject. Here’s Episode 172: William Herschel

Sources:

![Spring driven pendulum clock, designed by Huygens, built by instrument maker Salomon Coster (1657),[96] and copy of the Horologium Oscillatorium,[97] Museum Boerhaave, Leiden](https://www.universetoday.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/11/Christiaan_Huygens_Clock_and_Horologii_Oscillatorii-580x279.jpg)