There is something about them that intrigues us all. These massive spheres of gas burning intensely from the energy of fusion buried many thousands of kilometers deep within their cores. The stars have been the object of humanity’s wonderment for as far back as we have records. Many of humanity’s religions can be tied to worshiping these celestial candles. For the Egyptians, the sun was representative of the God Ra, who each day vanquished the night and brought light and warmth to the lands. For the Greeks, it was Apollo who drove his flaming chariot across the sky, illuminating the world. Even in Christianity, Jesus can be said to be representative of the sun given the striking characteristics his story holds with ancient astrological beliefs and figures. In fact, many of the ancient beliefs follow a similar path, all of which tie their origins to that of the worship of the sun and stars.

Humanity thrived off of the stars in the night sky because they recognized a correlation in the pattern in which certain star formations (known as constellations) represented specific times in the yearly cycle. One of which meant that it was to become warmer soon, which led to planting food. The other constellations foretold the coming of a

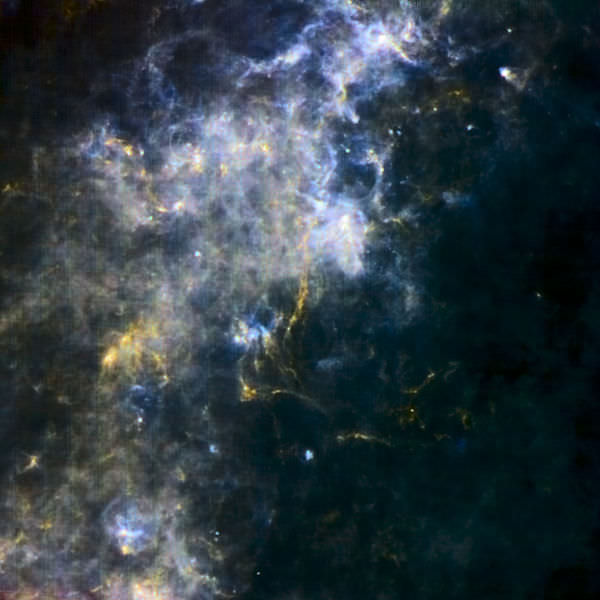

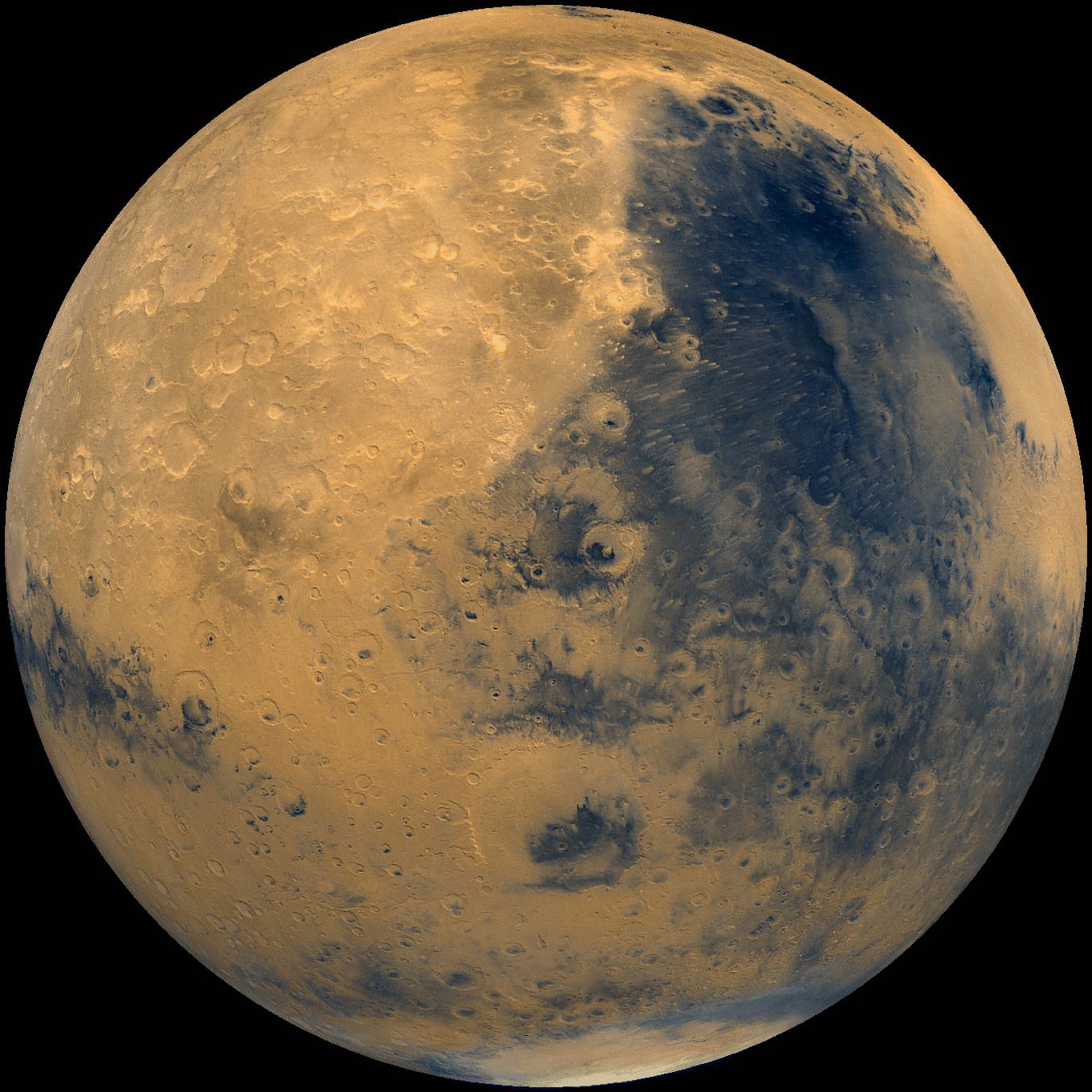

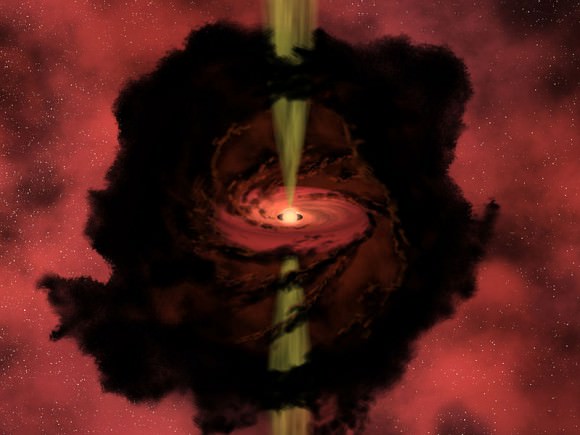

Credit: NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day Collection

NASA

colder period, so you were able to begin storing food and gathering firewood. Moving forward in humanity’s journey, the stars then became a way to navigate. Sailing by the stars was the way to get around, and we owe our early exploration to our understandings of the constellations. For many of the tens of thousands of years that human eyes have gazed upwards toward the heavens, it wasn’t until relatively recently that we fully began to understand what stars actually were, where they came from, and how they lived and died. This is what we shall discuss in this article. Come with me as we venture deep into the cosmos and witness physics writ large, as I cover how a star is born, lives, and eventually dies.

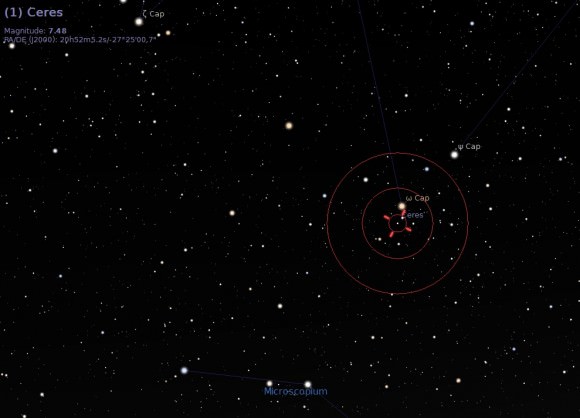

We begin our journey by traveling out into the universe in search of something special. We are looking for a unique structure where both the right circumstances and ingredients are present. We are looking for what astronomer’s call a Dark Nebula. I’m sure you’ve heard of nebulae before, and have no doubt seen them. Many of the amazing images that the Hubble Space Telescope has obtained are of beautiful gas clouds, glowing amidst the backdrop of billions of stars. Their colors range from deep reds, to vibrant blues, and even some eerie greens. This is not the type of nebula we are in search of though. The nebula we need is dark, opaque, and very, very cold.

You may by wondering to yourself, “Why are we looking for something dark and cold when stars are bright and hot?”

Indeed, this is something that would appear puzzling at first. Why does something need to be cold first before it can become extremely hot? First, we must cover something elementary about what we call the Interstellar Medium (ISM), or the space between the stars. Space is not empty as its name would imply. Space contains both gas and dust. The gas we are mainly referring to is Hydrogen, the most abundant element in the universe. Since the universe is not uniform (the same density of gas and dust over every cubic meter), there are pockets of space that contain more gas and dust than others. This causes gravity to manipulate these pockets to come together and form what we see as nebulae. Many things go into the making of these different nebulae, but the one that we are looking for, a Dark Nebula, possesses very special properties. Now, let us dive into one of these Dark Nebulae and see what is going on.

As we descend through the outer layers of this nebula, we notice that the temperature of the gas and dust is very low. In some nebulae, the temperatures are very hot. The more particles bump into each other, excited by the absorption and emission of exterior and interior radiation, means higher temperatures. But in this Dark Nebula, the opposite is happening. The temperatures are decreasing the further into the cloud we get. The reason these Dark Nebulae have specific properties that work to create a great stellar nursery has to deal with the basic properties of the nebula and the region type that the cloud exists in, which has some difficult concepts associated with it that I will not fully illustrate here. They include the region where the molecular clouds form which are called Neutral Hydrogen Regions, and the properties of these regions have to deal with electron spin values, along with magnetic field interactions that effect said electrons. The traits that I will cover are what allows for this particular nebula to be ripe for star formation.

Excluding the complex science behind what helps form these nebulae, we can begin to address the first question of why must we get colder to get hotter. The answer comes down to gravity. When particles are heated, or excited, they move faster. A cloud with sufficient energy will contain far too much momentum among each of the dust and gas particles for any type of formations to occur. As in, if dust grains and gas atoms are moving too quickly, they will simply bounce off of one another or just shoot past each other, never achieving any type of bond. Without this interaction, you can never have a star. However, if the temperatures are cold enough, the particles of gas and dust are moving so slow that their mutual gravity will allow for them to start to “stick” together. It is this process that allows for a protostar to begin to form.

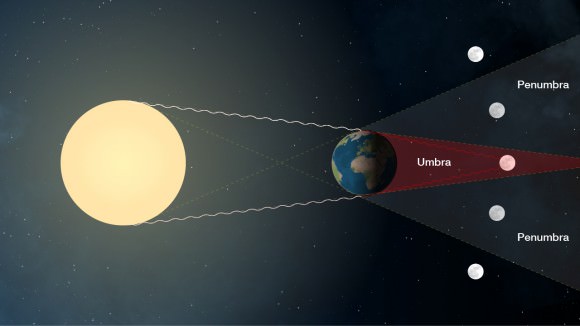

Generally what supplies energy to allow for the faster motion of the particles in these molecular clouds is radiation. Of course, there is radiation coming in from all directions at all times in the universe. As we see with other nebulae, they are glowing with energy and stars aren’t being born amid these hot gas clouds. They are being heated by external radiation from other stars and from its own internal heat. How does this Dark Nebula prevent external radiation from heating up the gas in the cloud and causing it to move too fast for gravity to take hold? This is where

the opaque nature of these Dark Nebulae comes into play. Opacity is the measure of how much light is able to move through an object. The more material in the object or the thicker the object is, the less light is able to penetrate it. The higher frequency light (Gamma Rays, X-Rays, and UV) and even the visible frequencies are affected more by thick pockets of gas and dust. Only the lower frequency types of light, including Infrared, Microwaves, and Radio Waves, has any success of penetrating gas clouds such as these, and even it is somewhat scattered so that generally they do not contain nearly enough energy to begin to disrupt this precarious process of star formation. Thus, the inner portions of the dark gas clouds are effectively “shielded” from the outside radiation that disrupts other, less opaque nebulae. The less radiation that makes it into the cloud, the lower the temperatures of the gas and dust within it. The colder temperatures means less particle motion within the cloud, which is key for what we will discuss next.

Indeed, as we descend towards the core of this dark molecular cloud, we notice that less and less visible light makes it to our eyes, and with special filters, we can see that this is true of other frequencies of light. As a result, the cloud’s temperature is very low. It is worth noting that the process of star formation takes a very long time, and in the interest of not keeping you reading for hundreds of thousands of years, we shall now fast forward time. In a few thousand years, gravity has pulled in a fair amount of gas and dust from the surrounding molecular cloud, causing it to clump together. Dust and gas particles, still shielded from outside radiation, are free to naturally come together and “stick” at these low temperatures. Eventually, something interesting begins to happen. The mutual gravity of this ever growing ball of gas and dust begins a snowball (or star-ball) effect. The more layers of gas and dust that are coagulated together, the denser the interior of this protostar becomes. This density increases the gravitational force near the protostar, thus pulling more material into it. With every dust grain and hydrogen atom that it accumulates, the pressure in the interior of this ball of gas increases.

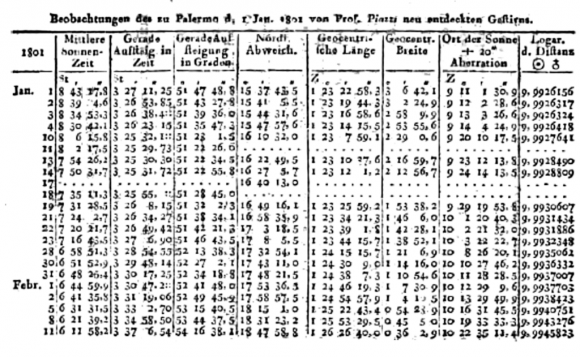

If you remember anything from any chemistry class you’ve ever taken, you may recall a very special relationship between pressure and temperature when dealing with a gas. PV=nRT, the Ideal Gas Law, comes to mind. Excluding the constant scalar value ‘n’ and the gas constant R ({8.314 J/mol x K}), and solving for Temperature (T), we get T=PV, which means that the temperature of a gas cloud is directly proportional to pressure. If you increase the pressure, you increase the temperature. The core of this soon-to-be star residing in this Dark Nebula is becoming very dense, and the pressure is skyrocketing. According to what we just calculated, that means that the temperature is also increasing.

We yet again consider this nebula for the next step. This nebula has a large amount of dust and gas (hence it being opaque), which means it has a lot of material to feed our protostar. It continues to pull in the gas and dust from its surrounding environment and begins heating up. The hydrogen particles in the core of this object are bouncing around so quick that they are releasing energy into the star. The protostar begins to get very hot and is now glowing with radiation (generally Infrared). At this point, gravity is still pulling in more gas and dust which is adding to the pressures exerted deep within the core of this protostar. The gas of the Dark Nebula will continue to collapse in on itself until something important happens. When there is little to nothing left near the star to fall onto its surface, it begins to lose energy (due to it radiating away as light). When this happens, that outward force lessens and gravity starts to contract the star faster. This greatly increases the pressure in the core of this protostar. As the pressure grows, the temperature in the core reaches a value that is crucial for the process that we are witnessing. The protostar’s core has become so dense and hot, that it reaches roughly 10 million Kelvin. To put that into perspective, this temperature is roughly 1700x hotter than the surface of our sun (at around 5800K). Why is 10 million Kelvin so important? Because at that temperature, the thermonuclear fusion of Hydrogen can occur, and once fusion starts, this newborn star “turns on” and bursts to life, sending out vast amounts of energy in all directions.

In the core, it is so hot that the electrons that zip around the hydrogen’s proton nuclei are stripped off (ionized), and all you have are free moving protons. If the temperature isn’t hot enough, these free flying protons (which have positive charges), will simply glance off one another. However, at 10 Million Kelvin, the protons are moving so fast that they can get close enough to allow for the Strong Nuclear Force to take over, and when it does the Hydrogen protons begin slamming into each other with enough force to fuse together, creating Helium atoms and releasing lots of energy in the form of radiation. It’s a chain reaction that can be summed up as 4 Protons yield 1 Helium atom + energy. This fusion is what ignites the star and causes it to “burn”. The energy liberated by this reaction goes into helping other Hydrogen protons fuse and also supplies the energy to keep the star from collapsing in on itself. The energy that is pumping out of this star in all directions all comes from the core, and the subsequent layers of this young star all transmit that heat in their own way (using radiation and convection methods depending upon what type of star has been born).

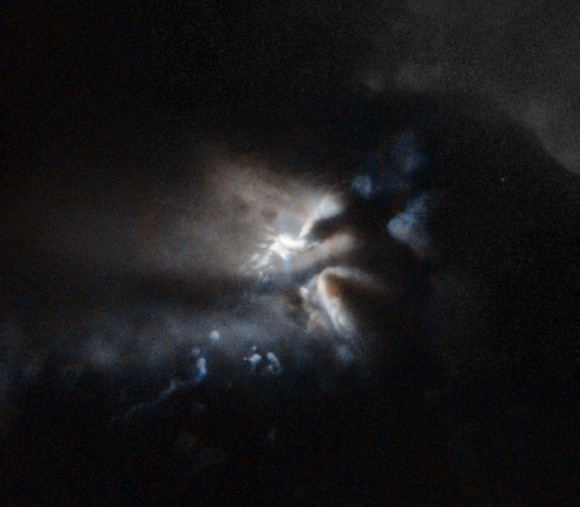

Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA Acknowledgement: Judy Schmidt

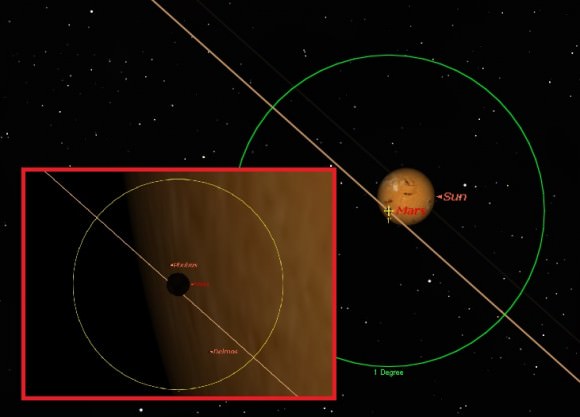

What we have witnessed now, from the start of our journey when we dove down into that cold Dark Nebula, is the birth of a young, hot star. The nebula protected this star from errant radiation that would have disrupted this process, as well as providing the frigid environment that was needed for gravity to take hold and work its magic. As we witnessed the protostar form, we may also have seen something incredible. If the contents of this nebula are right, such as having a high amount of heavy metals and silicates (left over from the supernovae of previous, more massive stars) what we could begin to see would be planetary formation taking place in the accretion disk of material around the protostar.

Remaining gas and dust in the vicinity of our new star would begin to form dense pockets by the same mechanism of

Credit: ESO/L. Calçada

http://www.eso.org/public/images/eso1310a/

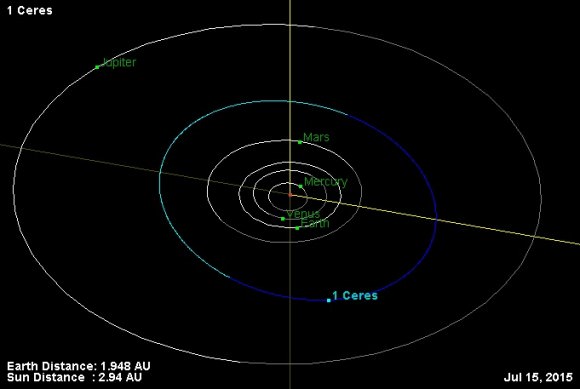

gravity, eventually being able to accrete into protoplanets that will be made up of gas or silicates and metal (or a combination of the two). That being said, planetary formation is still somewhat a mystery to us, as there seems to be things that we cannot explain yet at work. But this model of star system formation seems to work well.

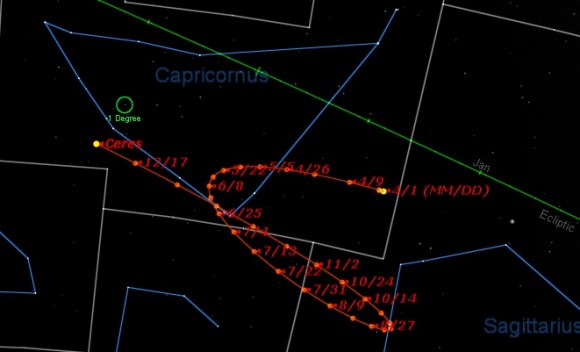

The life of the star isn’t nearly as exciting as its birth or death. We will continue to fast forward the clock and watch this star system evolve. Over a few billion years, the remnants of the Dark Nebula have been blown apart and have also formed other stars like the one we witnessed, and it no longer exists. The planets we saw being formed as the protostar grew begin their billion year dance around their parent star. Maybe on one of these worlds, a world that sits at just the right distance away from the star, liquid water exists. Within that water contains the amino acids that are needed for proteins (all composed of the elements that were left over by previous stellar eruptions). These proteins are able to link together to start to form RNA chains, then DNA chains. Maybe at one point a few billion years after the star has been born, we see a space-faring species launch itself into the cosmos, or perhaps they never achieve this for various reasons and remain planet-bound. Of course this is just speculation for our amusement. However, now we come to the end of our journey that began billions of years ago. The star begins to die.

The Hydrogen in its core is being fused into Helium, which depletes the Hydrogen over time; the star is running out of gas. After many years, the hydrogen fusion process begins to stop, and the star puts out less and less energy. This lack of outward pressure from the fusion process upsets what we call the hydrostatic equilibrium, and allows gravity (which is always trying to crush the star) to win. The star begins to shrink rapidly under its own weight. But, just as we discussed earlier, as the pressure increases, so too does the temperature. All of that Helium that was left over

Credit: NASA

from the billions of years of hydrogen fusion now begins to heat up in the core. Helium fuses at a much hotter temperature than Hydrogen does, which means that the Helium rich core is able to be pressed inward by gravity without fusing (yet). Since fusion isn’t occurring in the Helium core, there is little to no outward force (given off by fusion) to prevent the core from collapsing. This matter becomes much denser, which we now label as degenerate, and is pushing out massive amounts of heat (gravitational energy becoming thermal energy). This causes the remaining Hydrogen that is in subsequent layers above the Helium core to fuse, which causes the star to expand greatly as this Hydrogen shell burns out of control. This makes the star “rebound” and it expands rapidly; the more energetic fusion from the Hydrogen shells outside of the core expanding the diameter of the star greatly. Our star is now a red giant. Some, if not all of the inner planets that we witnessed form will be incinerated and swallowed up by the star that first gave them life. If there happened to be any life on any of those planets that didn’t manage to leave their home world, they would certainly be erased from the universe, never to be known of.

This process of the star running out of fuel (first Hydrogen, then Helium, etc…) will continue for a while. Eventually, the Helium in the core will reach a certain temperature and begin to fuse into Carbon, which will put off the collapse (and death) of the star. The star we are currently watching live and die is an average-sized Main Sequence Star, so its life ends once it is finished fusing Helium into

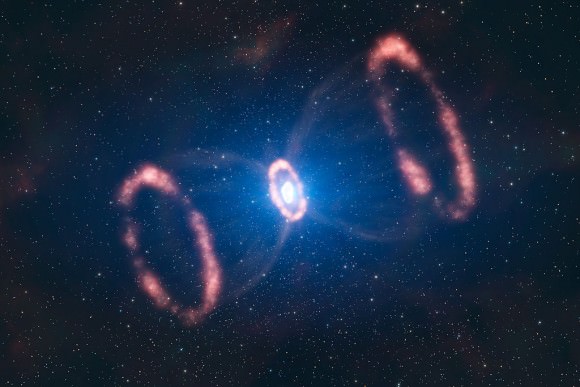

Credit: NASA

Carbon. If the star was much larger, this fusion process would proceed until we reached Iron. Iron is the element in which fusion does not take place spontaneously, meaning it requires more energy to fuse it than it gives off after fusion. However, our star will never make it to Iron in its core, and thus it has died after it exhausts its Helium reservoir. When the fusion process finally “turns off” (out of gas), the star slowly begins to cool and the outer layers of the star expand and are ejected into space. Subsequent ejections of stellar material proceed to create what we call a planetary nebula, and all that is left of the once brilliant star we watched spring into existence is now just a ball of dense carbon that will continue to cool for the rest of eternity, possibly crystallizing into diamond.

The death we witnessed just now isn’t the only way a star dies. If a star is sufficiently large enough, its death is much more violent. The star will erupt into the largest explosion in the universe, called a supernova. Depending on many variables, the remnant of the star could end up as a neutron star, or even a black hole. But for most of what we call the average sized Main Sequence Stars, the death that we witnessed will be their fate.

Credit: ESO/L. Calçada

Our journey ends with us pondering what we have observed. Seeing just what nature can do given the right circumstances, and watching a cloud of very cold gas and dust turn into something that has the potential to breathe life into the cosmos. Our minds wander back to that species that could have evolved on one of those planets. You think about how they may have gone through phases similar to us. Possibly using the stars as supernatural deities that guided their beliefs for thousands of years, substituting answers in for where their ignorance reigned. These beliefs could possibly turn into religions, still grasping that notion of special selection and magnanimous thought. Would the stars fuel their desire to understand the universe as the stars did for us? Your mind then ponders what our fate will be if we do not attempt to take the next step into the universe. Are we to allow our species to be erased from the cosmos as our star expands in its death? This journey you just made into the heart of a Dark Nebula truly exemplifies what the human mind can do, and shows you just how far we have come even though we are still bound to our solar system. The things you have learned were found by others like you simply asking how things occur and then bringing the full weight of our knowledge of physics to bare. Imagine what we can accomplish if we continue this process; being able to fully achieve our place among the stars.

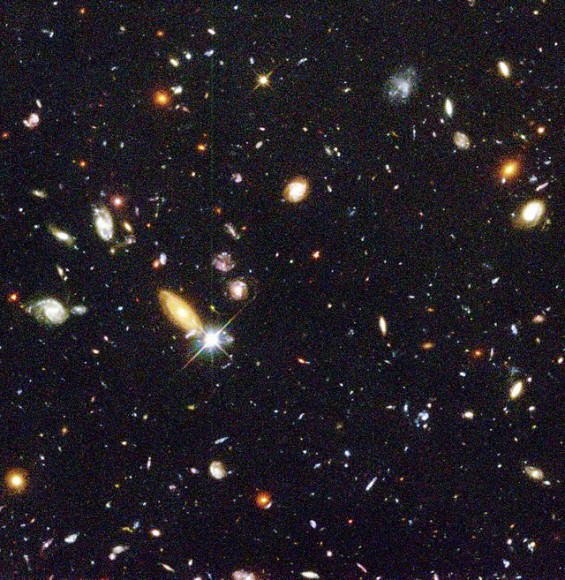

Credit: NASA (Hubble Deep Field)