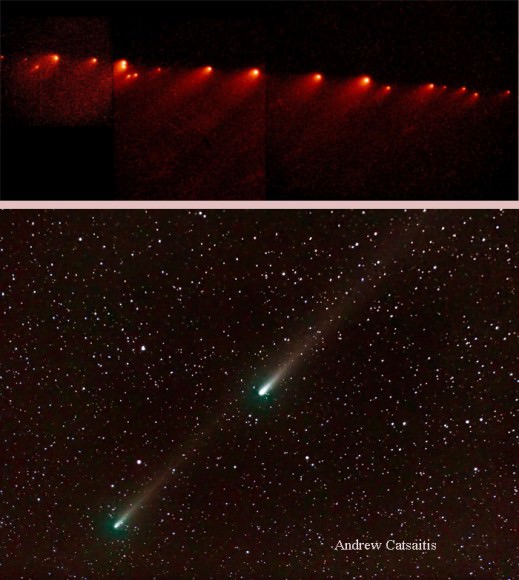

A telescope peers into the blackness of deep space. Suddenly – a brilliant flash of light appears that wasn’t there before. What could it be? A supernova? Two massively dense stars fusing together? Perhaps a gamma ray burst?

Five years ago, researchers using the ROTSE IIIb telescope at McDonald Observatory noticed just such an event. But far from being your run-of-the-mill stellar explosion or neutron star merger, the astronomers believe that this tiny flare was, in fact, evidence of a supermassive black hole at the center of a distant galaxy, tearing a star to shreds.

Astronomers at McDonald had been using the telescope to scan the skies for such nascent flashes for years, as part of the ROTSE Supernova Verification Project (SNVP). And at first blush, the event seen in early 2009, which the researches nicknamed “Dougie,” looked just like many of the other supernovae they had discovered over the course of the project. With a blazing – 22.5-magnitude absolute brightness, the event fit squarely within the class of superluminous supernovae that the researchers were already familiar with.

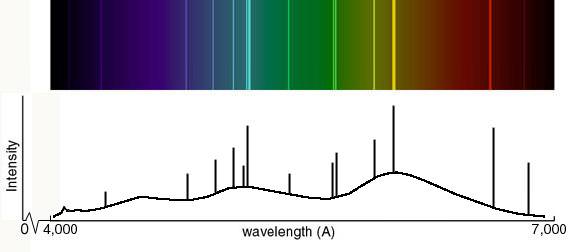

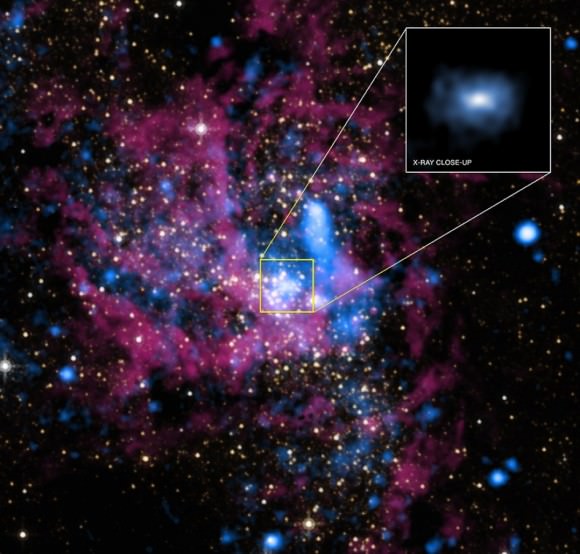

But as time went on and more data on Dougie rolled in, the astronomers began to change their minds. X-ray observations made by the orbiting Swift satellite and optical spectra taken by McDonald’s Hobby-Eberly Telescope revealed an evolving light curve and chemical makeup that didn’t fit with computer simulations of superluminous supernovae. Likewise, Dougie didn’t appear to be a neutron star merger, which would have reached peak luminosity far more quickly than was observed, or a gamma ray burst, which, even at an angle, would have appeared far brighter in x-ray light.

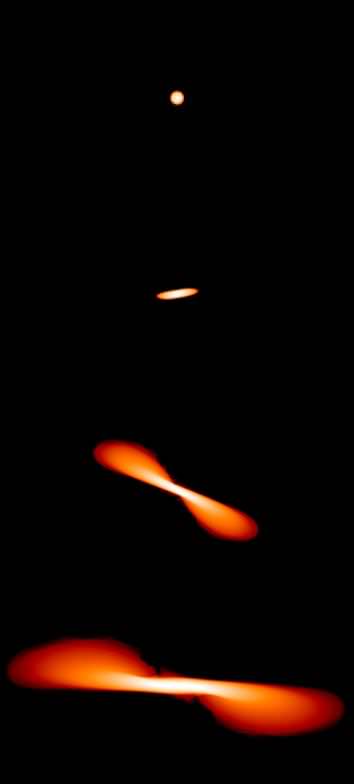

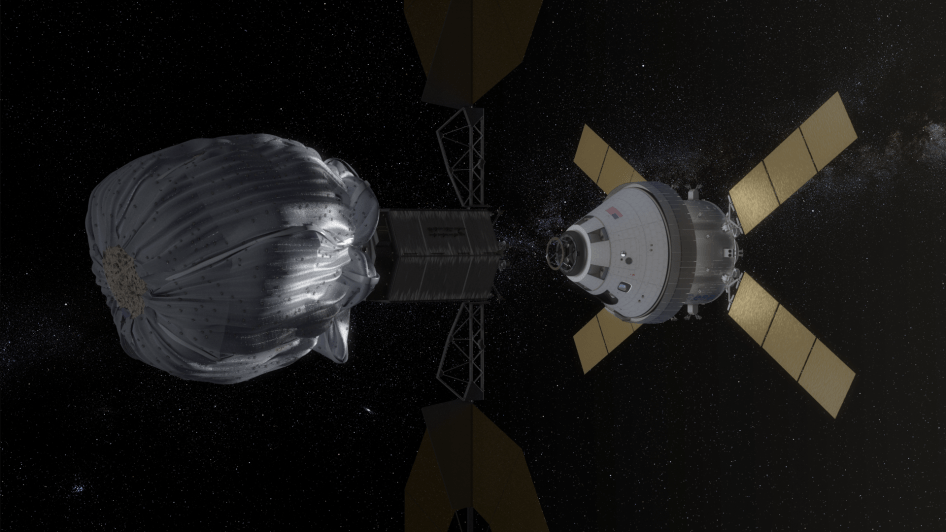

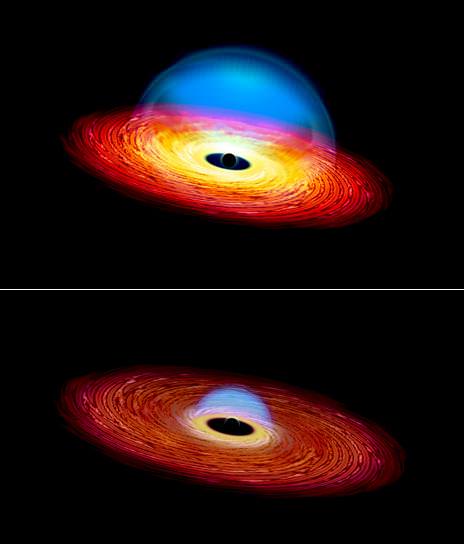

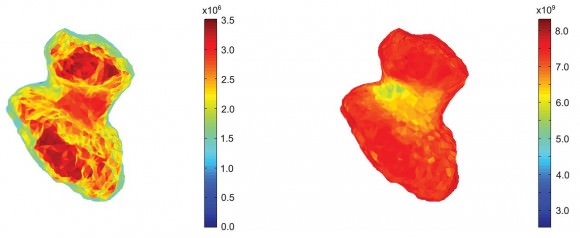

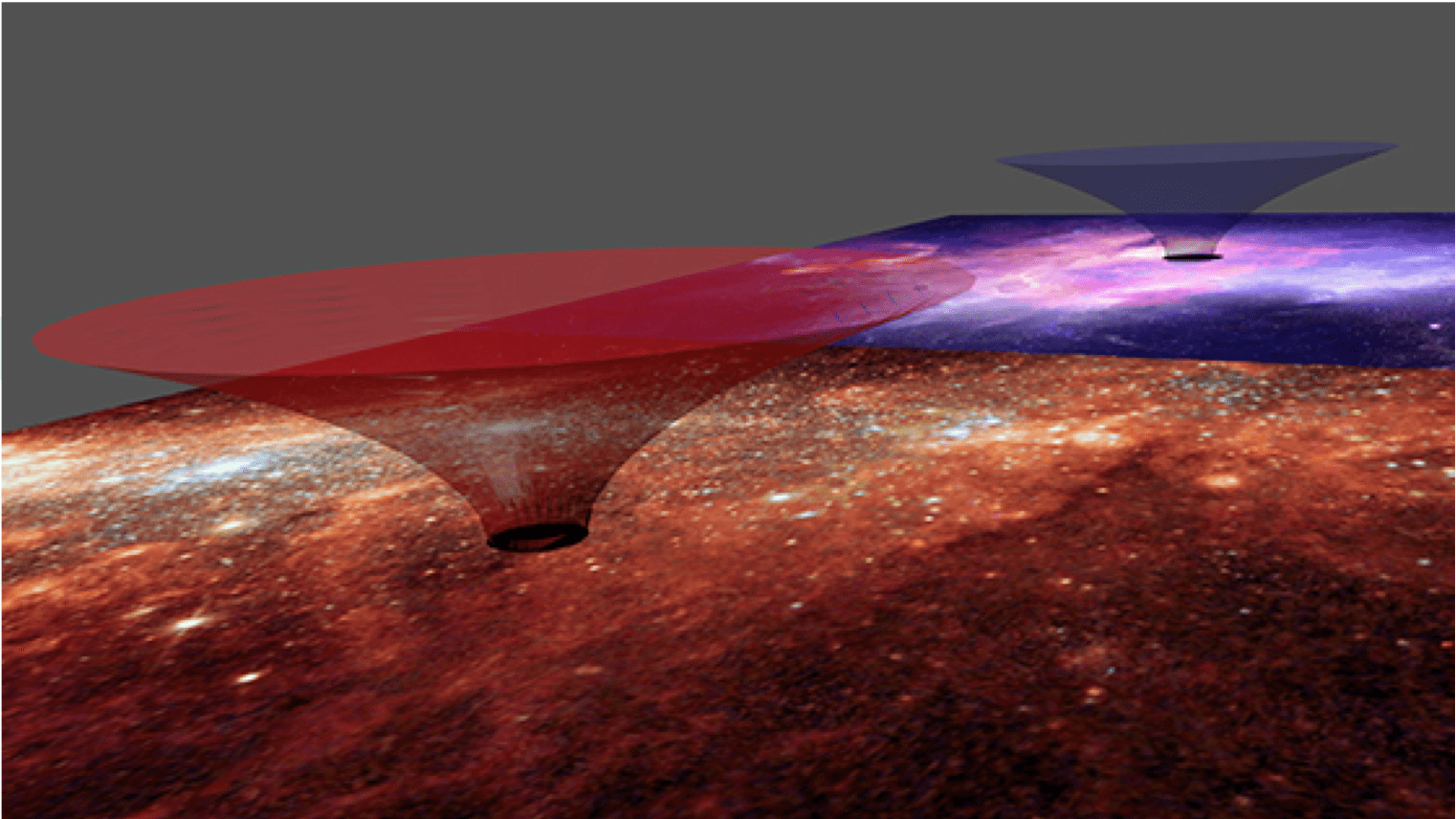

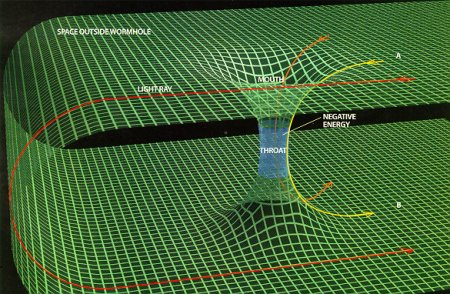

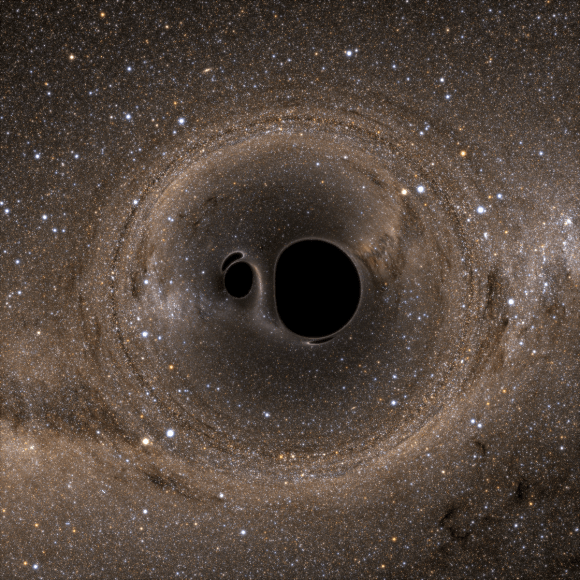

That left only one option: a so-called “tidal disruption event,” or the carnage and spaghettification that occurs when a star wanders too close to a black hole’s horizon. J. Craig Wheeler, head of the supernova group at The University of Texas at Austin and a member of the team that discovered Dougie, explained that at short distances, a black hole’s gravity exerts a much stronger pull on the side of the star nearest to it than it does on the star’s opposite side. He explained, “These especially large tides can be strong enough that you pull the star out into a noodle.”

The team refined their models of the event and came to a surprising conclusion: having drawn in Dougie’s stellar material a bit faster than it could handle, the black hole was now “choking” on its latest meal. This is due to an astrophysical principle called the Eddington Limit, which states that a black hole of a given size can only handle so much infalling material. After this limit has been reached, any additional intake of matter exerts more outward pressure than the black hole’s gravity can compensate for. This pressure increase has a kind of rebound effect, throwing off material from the black hole’s accretion disk along with heat and light. Such a burst of energy accounts for at least part of Dougie’s brightness, but also indicates that the original dying star – a star not unlike our own Sun – wasn’t going down without a fight.

Combining these observations with the mathematics of the Eddington Limit, the researchers estimated the black hole’s size to be about 1 million solar masses – a rather small black hole, at the center of a rather small galaxy, three billion light years away. Discoveries like these not only allow astronomers to better understand the physics of black holes, but also properties of their often unassuming home galaxies. After all, mused Wheeler, “Who knew this little guy had a black hole?”

To get a simulated glimpse of Dougie for yourself, check out the amazing animation below, courtesy of team member James Guillochon:

The research is published in this month’s issue of The Astrophysical Journal. A pre-print of the paper is available here.