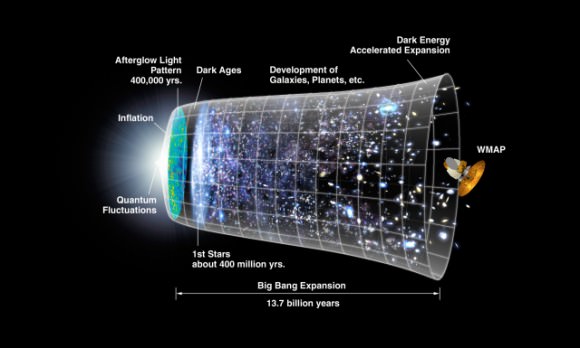

Dark matter is the architect of large-scale cosmic structure and the engine behind proper rotation of galaxies. It’s an indispensable part of the physics of our Universe – and yet scientists still don’t know what it’s made of. The latest data from Planck suggest that the mysterious substance comprises 26.2% of the cosmos, making it nearly five and a half times more prevalent than normal, everyday matter. Now, four European researchers have hinted that they may have a discovery on their hands: a signal in x-ray light that has no known cause, and may be evidence of a long sought-after interaction between particles – namely, the annihilation of dark matter.

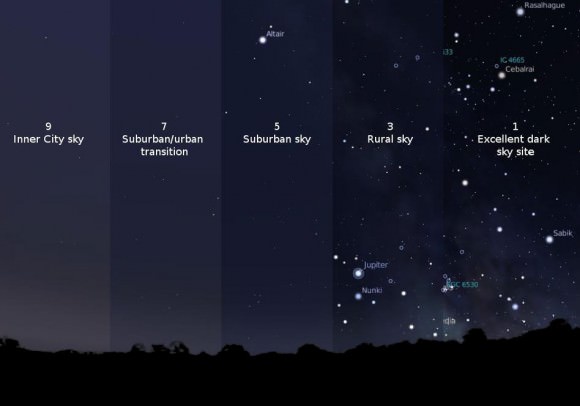

When astronomers want to study an object in the night sky, such as a star or galaxy, they begin by analyzing its light across all wavelengths. This allows them to visualize narrow dark lines in the object’s spectrum, called absorption lines. Absorption lines occur because a star’s or galaxy’s component elements soak up light at certain wavelengths, preventing most photons with those energies from reaching Earth. Similarly, interacting particles can also leave emission lines in a star’s or galaxy’s spectrum, bright lines that are created when excess photons are emitted via subatomic processes such as excitement and decay. By looking closely at these emission lines, scientists can usually paint a robust picture of the physics going on elsewhere in the cosmos.

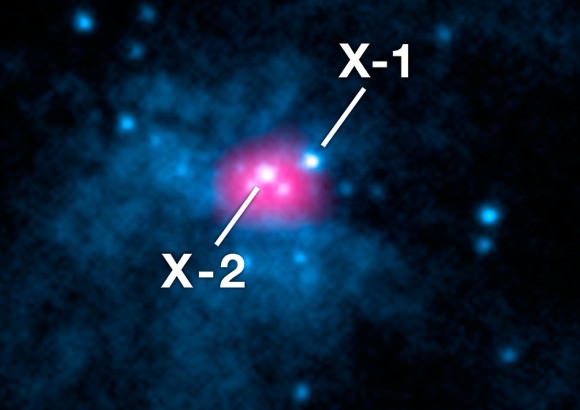

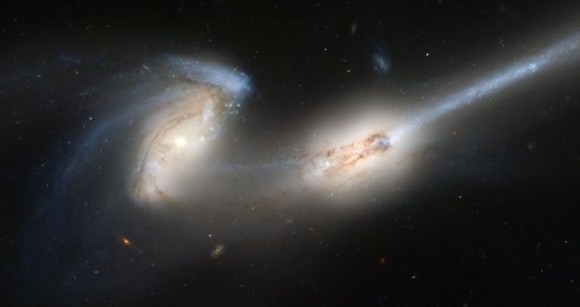

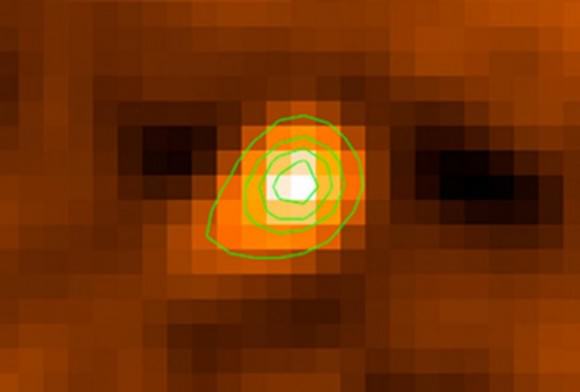

But sometimes, scientists find an emission line that is more puzzling. Earlier this year, researchers at the Laboratory of Particle Physics and Cosmology (LPPC) in Switzerland and Leiden University in the Netherlands identified an excess bump of energy in x-ray light coming from both the Andromeda galaxy and the Perseus star cluster: an emission line with an energy around 3.5keV. No known process can account for this line; however, it is consistent with models of the theoretical sterile neutrino – a particle that many scientists believe is a prime candidate for dark matter.

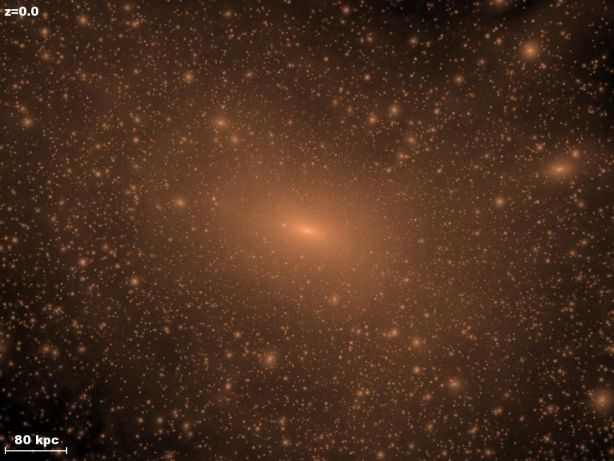

The researchers believe that this strange emission line could result from the annihilation, or decay, of these dark matter particles, a process that is thought to release x-ray photons. In fact, the signal appeared to be strongest in the most dense regions of Andromeda and Perseus and increasingly more diffuse away from the center, a distribution that is also characteristic of dark matter. Additionally, the signal was absent from the team’s observations of deep, empty space, implying that it is real and not just instrumental artifact.

In a pre-print of their paper, the researchers are careful to stress that the signal itself is weak by scientific standards. That is, they can only be 99.994% sure that it is a true result and not just a rogue statistical fluctuation, a level of confidence that is known as 4σ. (The gold standard for a discovery in science is 5σ: a result that can be declared “true” with 99.9999% confidence) Other scientists are not so sure that dark matter is such a good explanation after all. According to predictions made based on measurements of the Lyman-alpha forest – that is, the spectral pattern of hydrogen absorption and photon emission within very distant, very old gas clouds – any particle purporting to be dark matter should have an energy above 10keV – more than twice the energy of this most recent signal.

As always, the study of cosmology is fraught with mysteries. Whether this particular emission line turns out to be evidence of a sterile neutrino (and thus of dark matter) or not, it does appear to be a signal of some physical process that scientists do not yet understand. If future observations can increase the certainty of this discovery to the 5σ level, astrophysicists will have yet another phenomena to account for – an exciting prospect, regardless of the final result.

The team’s research has been accepted to Physical Review Letters and will be published in an upcoming issue.