Comet Q2 Lovejoy passed closest to Earth on January 7th and has been putting on a great show this past week. Glowing at magnitude +4 with a bluish coma nearly as big as the Full Moon, the comet’s easy to see with the naked eye from the right location if you know exactly where to look. I wish I could say just tilt your head back and look up and bam! there it would be, but it’ll take a little more effort than that. But just a little, I promise.

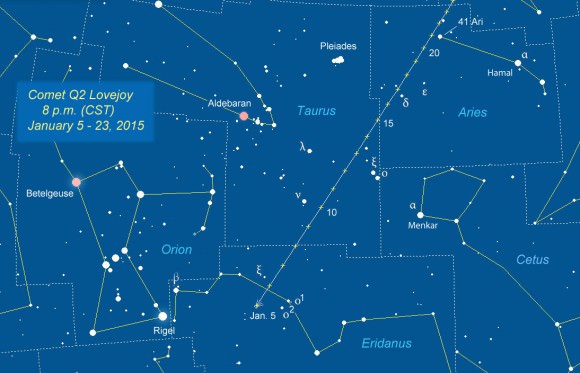

Last night, under a dark rural sky, once I spotted the comet and noticed its position in relation to nearby bright stars, I could look up and see it anytime. Finding anything other than the Moon or a bright planet in the night sky often requires a good map. I normally create a star-chart style map but thought, why not make a photographic version? So last night I snapped a few guided images of Lovejoy as it glimmered in the wilds of southern Taurus and then cloned the comet’s nightly position through onto the image. Maybe you’ll find this useful, maybe not. If not, the regular map is also included.

To see Comet Lovejoy with the naked eye you’ll need reasonably dark skies. It should be faintly visible from outer ring suburbs, but country skies will guarantee a sighting. I’ve been using bright stars in Orion and Taurus to guide binoculars – and then my eye – to the comet. Pick a couple bright stars like Aldebaran and Betelgeuse and extend a line from each to form a triangle with Lovejoy at one of the corners. If you then point binoculars at that spot in the sky, the comet should pop out. If you don’t find it immediately, sweep around the position a bit. After you find it, lower the binoculars and try to spot it with the naked eye.

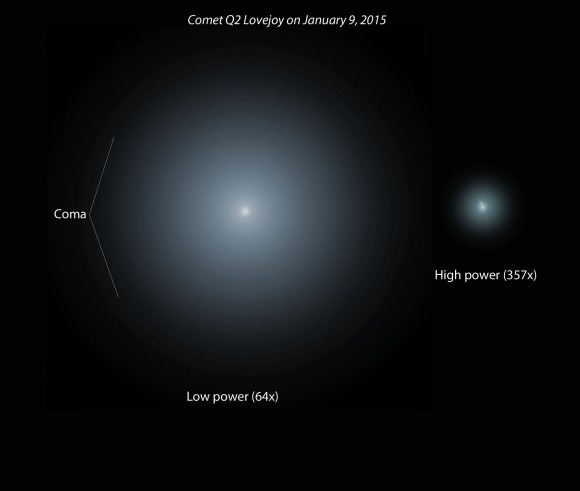

This week, as Lovejoy continues trekking north, you can use bright orangey Aldebaran in Taurus and the Pleiades, also called the Seven Sisters star cluster, to “triangulate” your way to the comet. Look for a glowing fuzzball. In 10×50 and 8×40 binoculars, it’s obviously different from a star — all puffed up with a brighter center. The 50mm glass even shows a hint of the coma’s blue color caused by carbon molecules fluorescing in ultraviolet sunlight and a faint, streak-like tail extending to the northeast. With the naked eye, at first you might think it’s just a dim star; closer scrutiny reveals the star has a hazy appearance, pegging it as a comet.

Through a telescope the coma is a HUGE pale blue tiki lamp of a thing with a small, much brighter nuclear region. The rays of the ion tail, so beautifully shown in photographs, are indistinct but visible with patience and a moderate-sized telescope under dark skies. At low magnification, the nucleus – the false nucleus actually, since the real comet nucleus is hidden by a shroud of dust and gas – looks like a misty star of about magnitude +9. On close inspection at high magnification (250x and up), you penetrate more deeply into the nuclear zone and the star-like center shrinks and dims to around magnitude +13.

If the seeing is good and comet active, high magnification will often reveal jets or fans of dust in the sunward direction, in this case west of nucleus. I’ve been studying the comet the past couple nights and am almost convinced I can see a short, very low contrast plume poking to the south of center. Generally, plumes and jets are subtle, low-contrast features. Challenging? Yes, but with Lovejoy as close as it’s going to get, now’s the time to seek them.

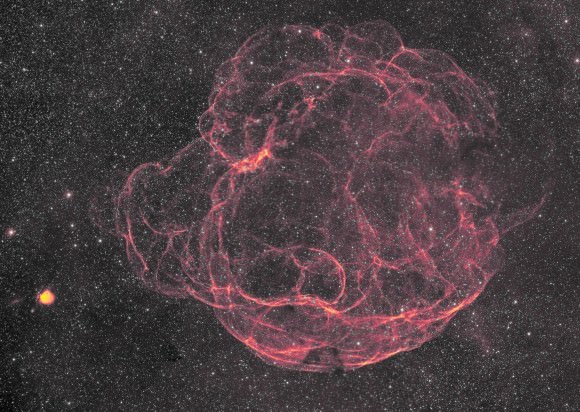

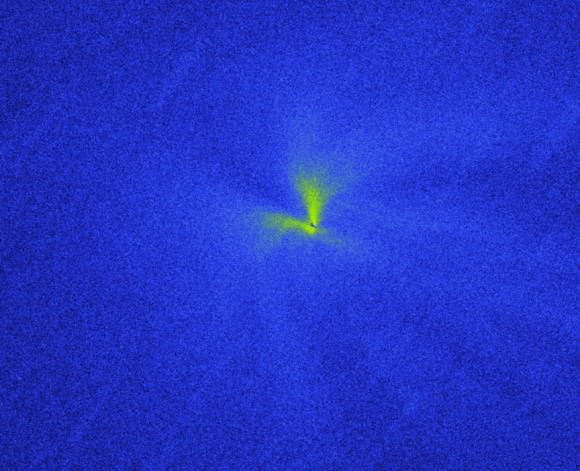

Just before Christmas, fluctuations in the solar wind snapped off Comet Lovejoy’s tail. Guess what? It happened again on January 8th as recorded in dramatic fashion by astrophotographer Rolando Ligustri. An ion or gas tail like the one in the photo forms when cometary gases, primarily carbon monoxide, are ionized by solar radiation and lose an electron to become positively charged. Once “electrified”, they can be twisted, kinked and even snapped off by magnetic fields embedded in the Sun’s particle wind.

Of course, the comet didn’t miss a breath but grew another tail immediately. Look closely at the photo and you see another faint streak of light pointing beyond the coma below and left of the bright nuclear region. This may be Lovejoy’s dust tail. Most comets sport both types of tails – gas and dust – since they release both materials as the Sun heats and vaporizes their ices.

Lovejoy’s been a thrill to watch because it’s doing all the cool stuff that makes them so fun to follow. Gianluca Masi, an Italian astrophysicist and lover of all things cometary, will offer a live feed of the comet on Monday January 12th starting at 1 p.m. CST (7 p.m. UT). May your skies be clear tonight!