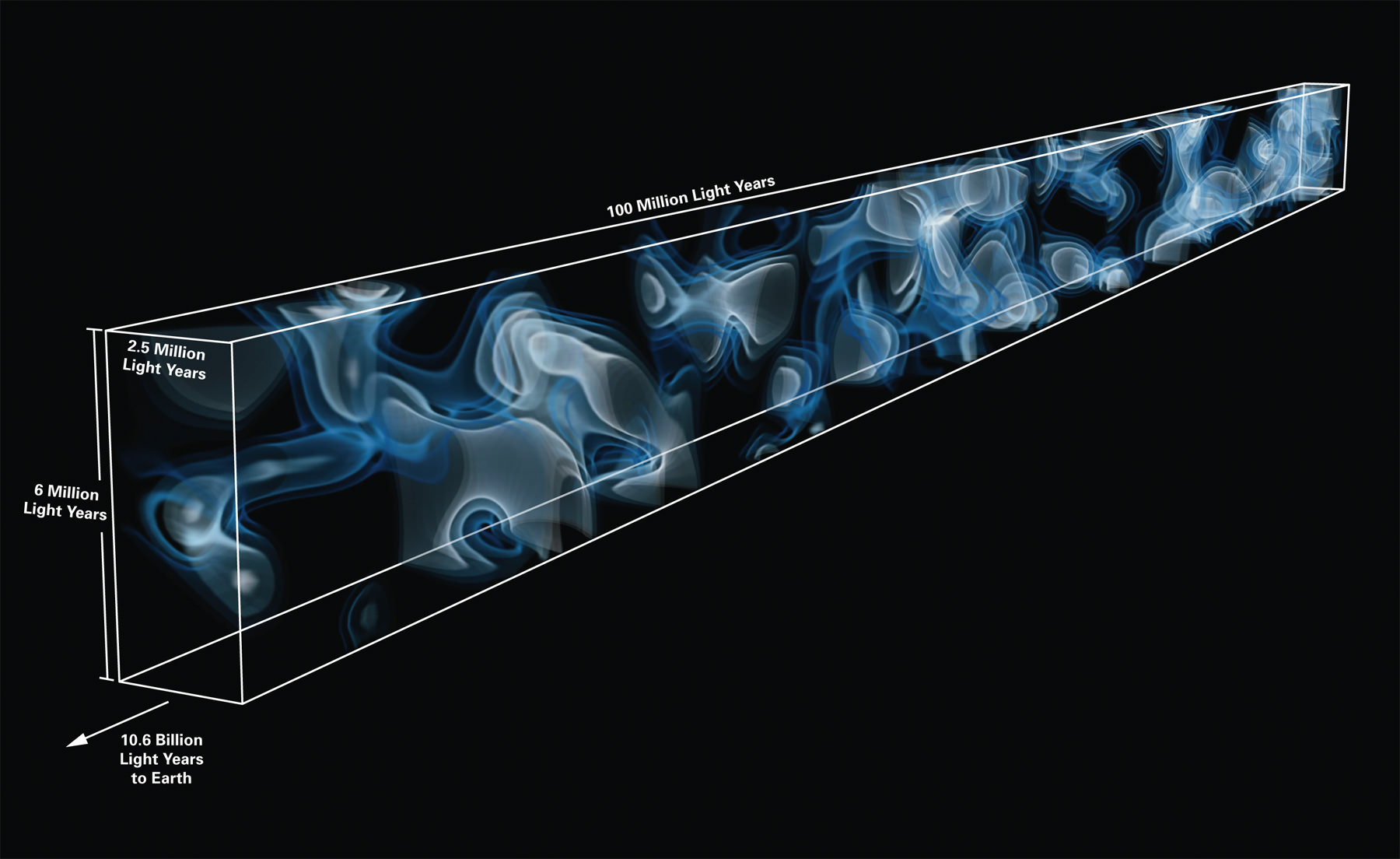

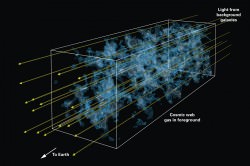

On the largest scales, networks of gaseous filaments span hundreds of millions of light-years, connecting massive galaxy clusters. But this gas is so rarified, it’s impossible to see directly.

For years, astronomers have used quasars — brilliant galactic centers fueled by supermassive black holes rapidly accreting material — to map the otherwise invisible matter.

But now, for the first time, a team of astronomers led by Khee-Gan Lee, a post-doc at the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy, has managed to create a three-dimensional map of the large-scale structure of the Universe using distant galaxies. And the advantages are numerous.

The science has always gone a little something like this: as the bright light from a distant quasar travels toward Earth, it encounters the intervening clouds of hydrogen gas and is partially absorbed. This leaves dark absorption lines in the quasar’s spectrum.

If the Universe were static, the dark absorption lines would always be located at the same spot (121 nanometers for the so-called Lyman-alpha line) in the quasar’s spectrum. But because the Universe is expanding, the distant quasar is flying away from the Earth at a rapid speed. This stretches the quasar’s light, such that each intervening hydrogen gas cloud imprints its absorption signature on a different region of the quasar’s spectrum, leaving a forest of lines.

Therefore detailed measurements of multiple quasars’ spectra close together can actually reveal the three-dimensional nature of the intervening hydrogen clouds. But galaxies are nearly 100 times more numerous than quasars. So in theory they should provide a much more detailed map.

The only problem is that galaxies are also about 15 times fainter than quasars. So astronomers thought they were simply not bright enough to see well in the distant universe. But Lee carried out calculations that suggested otherwise.

“I was surprised to find that existing large telescopes should already be able to collect sufficient light from these faint galaxies to map the foreground absorption, albeit at a lower resolution than would be feasible with future telescopes,” said Lee in a news release. “Still, this would provide an unprecedented view of the cosmic web which has never been mapped at such vast distances.”

Lee and his colleagues used the 10-meter Keck I telescope on Mauna Kea, Hawaii to take a look a closer look at the distant galaxies and the forest of hydrogen absorption embedded in their spectra. But even the weather in Hawaii can turn ugly.

“We were pretty disappointed as the weather was terrible and we only managed to collect a few hours of good data,” said coauthor Joseph Hennawi, also from the Max Planck Institute for Astronomy. “But judging by the data quality as it came off the telescope, it was already clear to me that the experiment was going to work.”

The team was only able to collect data for four hours. But it was still unprecedented. They looked at 24 distant galaxies, which provided sufficient coverage of a small patch of the sky and allowed them to combine the information into a three-dimensional map.

The map reveals the large-scale structure of the Universe when it was only a quarter of its current age. But the team hopes to soon parse the map for more information about the structure’s function — following the flows of cosmic gas as it funneled away from voids and onto distant galaxies. It will provide a unique historical record on how the galaxy clusters and voids grew from inhomogeneities in the Big Bang.

The results have been published in the Astrophysical Journal and are available online.