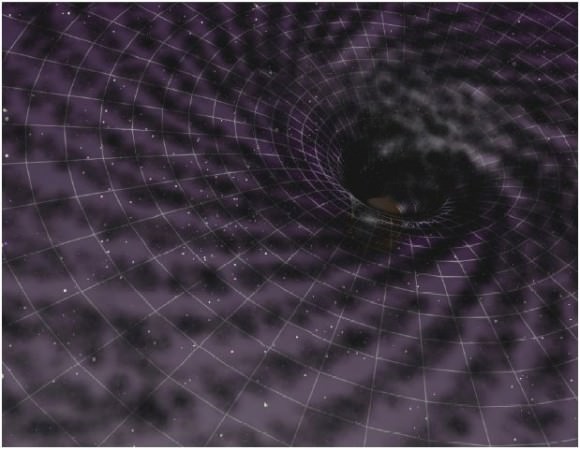

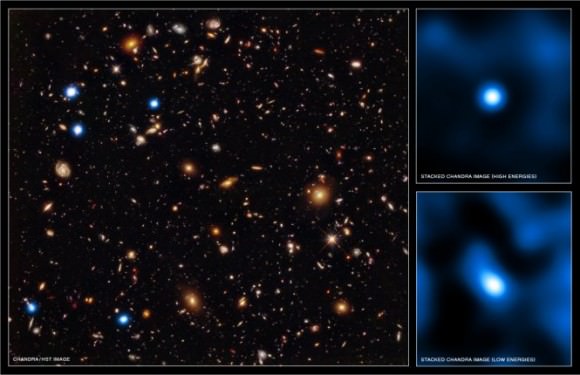

It’s one of the puzzles of cosmology and stellar evolution: how did supermassive black holes get so… well, supermassive… in the early Universe, when seemingly not enough time had yet passed for them to accumulate their mass through steady accretion processes alone? It takes a while to eat up a billion solar masses’ worth of matter, even with a healthy appetite and lots within gravitational reach. But yet there they are: monster black holes are common within some of the most distant galaxies, flaunting their precocious growth even as the Universe was just celebrating its one billionth birthday.

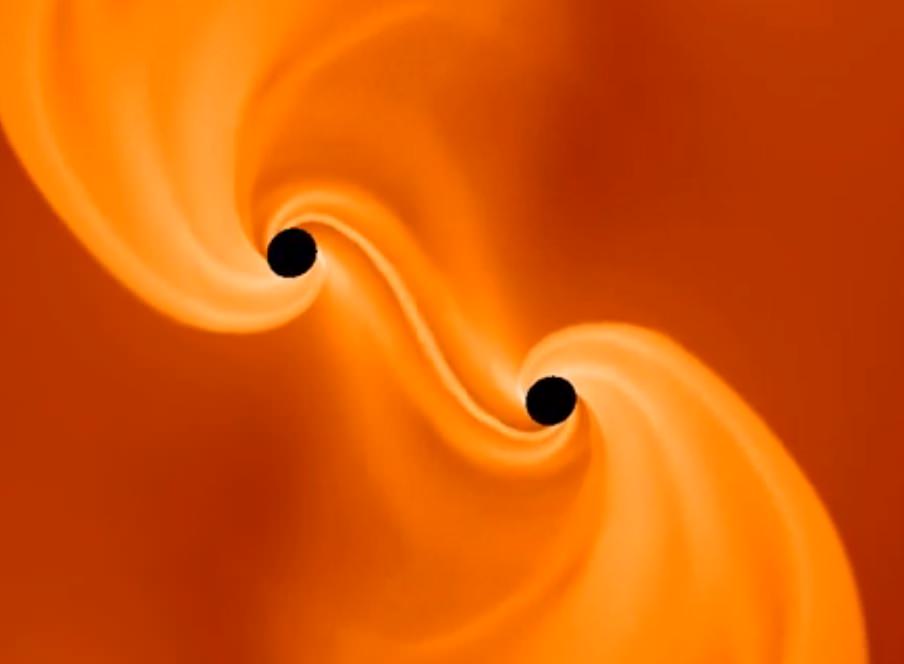

Now, recent findings by researchers at Caltech suggest that these ancient SMBs were formed by the death of certain types of primordial giant stars, exotic stellar dinosaurs that grew large and died young. During their violent collapse not just one but two black holes are formed, each gathering its own mass before eventually combining together into a single supermassive monster.

Watch a simulation and find out more about how this happens below:

From a Caltech news article by Jessica Stoller-Conrad:

To investigate the origins of young supermassive black holes, Christian Reisswig, NASA Einstein Postdoctoral Fellow in Astrophysics at Caltech and Christian Ott, assistant professor of theoretical astrophysics, turned to a model involving supermassive stars. These giant, rather exotic stars are hypothesized to have existed for just a brief time in the early Universe.

Read more: How Do Black Holes Get Super Massive?

Unlike ordinary stars, supermassive stars are stabilized against gravity mostly by their own photon radiation. In a very massive star, photon radiation—the outward flux of photons that is generated due to the star’s very high interior temperatures—pushes gas from the star outward in opposition to the gravitational force that pulls the gas back in.

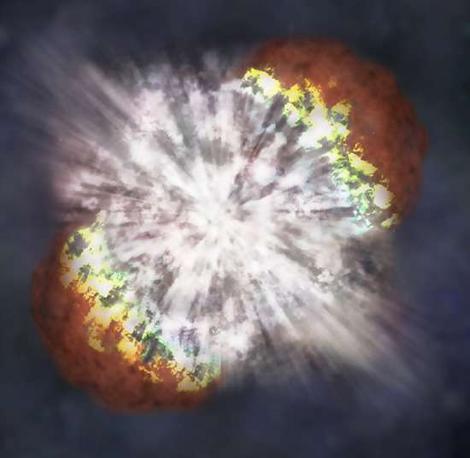

During its life, a supermassive star slowly cools due to energy loss through the emission of photon radiation. As the star cools, it becomes more compact, and its central density slowly increases. This process lasts for a couple of million years until the star has reached sufficient compactness for gravitational instability to set in and for the star to start collapsing gravitationally.

Previous studies predicted that when supermassive stars collapse, they maintain a spherical shape that possibly becomes flattened due to rapid rotation. This shape is called an axisymmetric configuration. Incorporating the fact that very rapidly spinning stars are prone to tiny perturbations, Reisswig and his colleagues predicted that these perturbations could cause the stars to deviate into non-axisymmetric shapes during the collapse. Such initially tiny perturbations would grow rapidly, ultimately causing the gas inside the collapsing star to clump and to form high-density fragments.

“The growth of black holes to supermassive scales in the young universe seems only possible if the ‘seed’ mass of the collapsing object was already sufficiently large.”

– Christian Reisswig, NASA Einstein Postdoctoral Fellow at Caltech

These fragments would orbit the center of the star and become increasingly dense as they picked up matter during the collapse; they would also increase in temperature. And then, Reisswig says, “an interesting effect kicks in.” At sufficiently high temperatures, there would be enough energy available to match up electrons and their antiparticles, or positrons, into what are known as electron-positron pairs. The creation of electron-positron pairs would cause a loss of pressure, further accelerating the collapse; as a result, the two orbiting fragments would ultimately become so dense that a black hole could form at each clump. The pair of black holes might then spiral around one another before merging to become one large black hole.

“This is a new finding,” Reisswig says. “Nobody has ever predicted that a single collapsing star could produce a pair of black holes that then merge.”

These findings were published in Physical Review Letters the week of October 11. Source: Caltech news article by Jessica Stoller-Conrad.