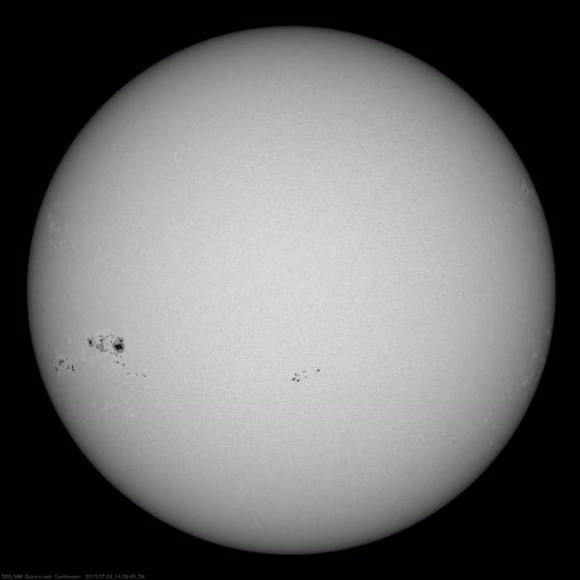

Since their discovery, supermassive black holes – the giants lurking in the center of every galaxy – have been mysterious in origin. Astronomers remain baffled as to how these supermassive black holes became so massive.

New research explains how a supermassive black hole might begin as a normal black hole, tens to hundreds of solar masses, and slowly accrete more matter, becoming more massive over time. The trick is in looking at a binary black hole system. When two galaxies collide the two supermassive black holes sink to the center of the merged galaxy and form a binary pair. The accretion disk surrounding the two black holes becomes misaligned with respect to the orbit of the binary pair. It tears and falls onto the black hole pair, allowing it to become more massive.

In a merging galaxy the gas flows are turbulent and chaotic. Because of this “any gas feeding the supermassive black hole binary is likely to have angular momentum that is uncorrelated with the binary orbit,” Dr. Chris Nixon, lead author on the paper, told Universe Today. “This makes any disc form at a random angle to the binary orbit.

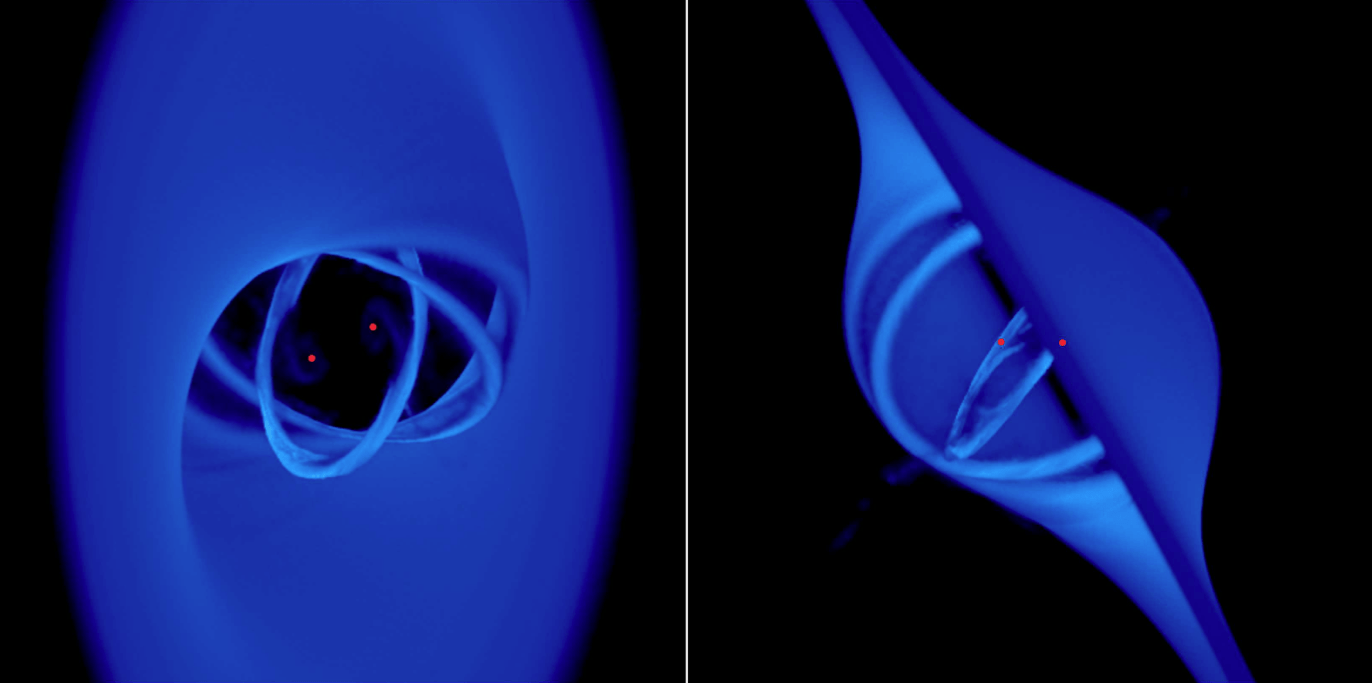

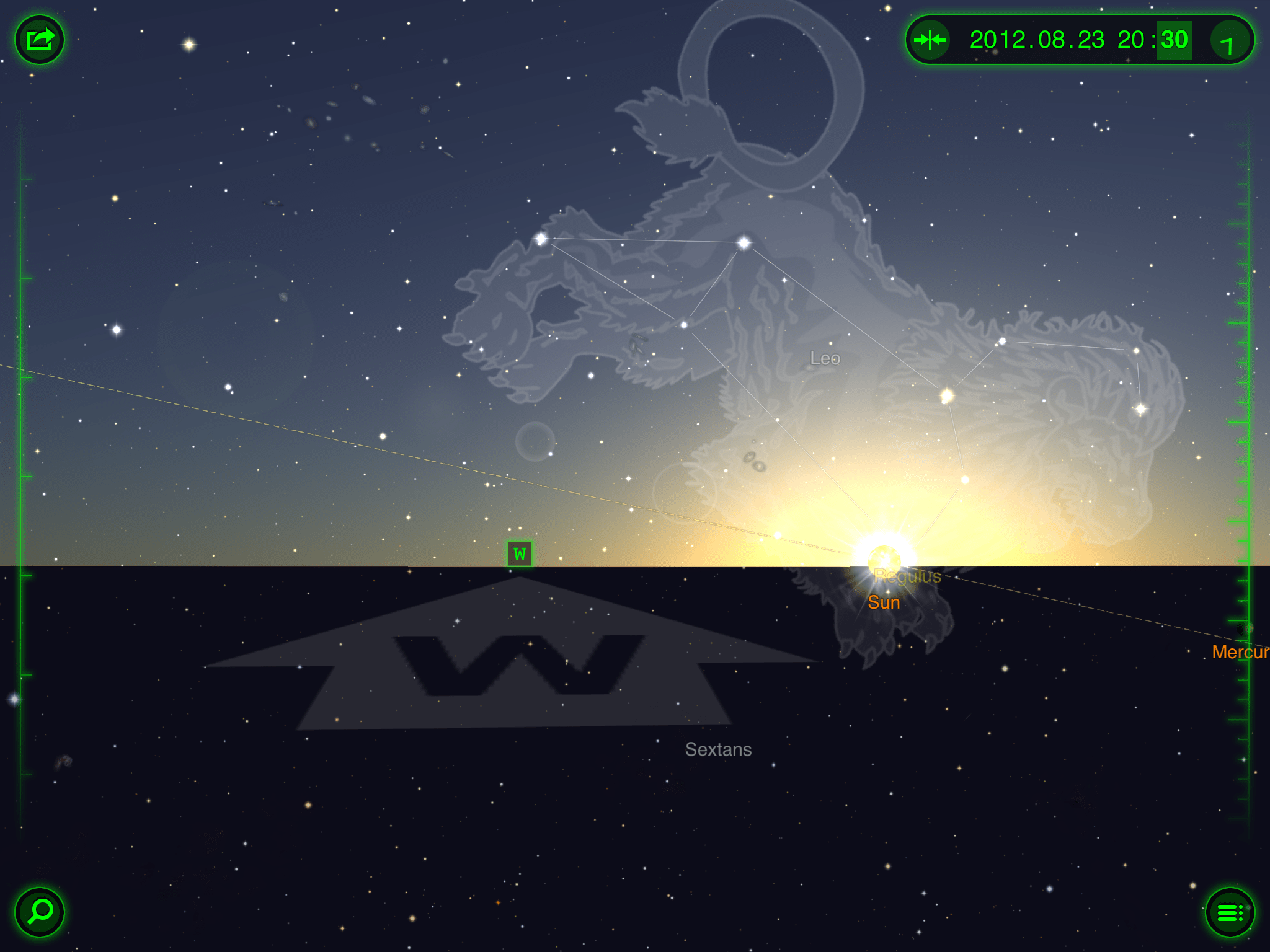

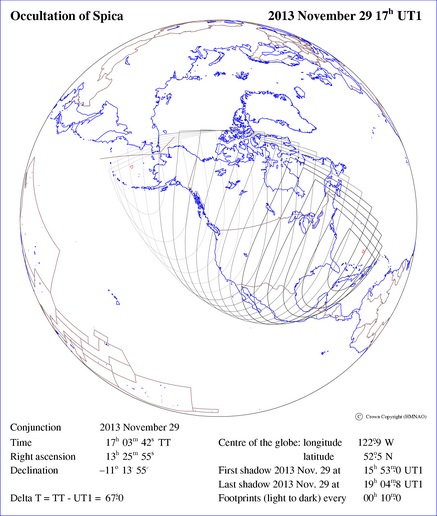

Nixon et al. examined the evolution of a misaligned disk around a binary black hole system using computer simulations. For simplicity they analyzed a circular binary system of equal mass, acting under the effects of Newtonian gravity. The only variable in their models was the inclination of the disk, which they varied from 0 degrees (perfectly aligned) to 120 degrees.

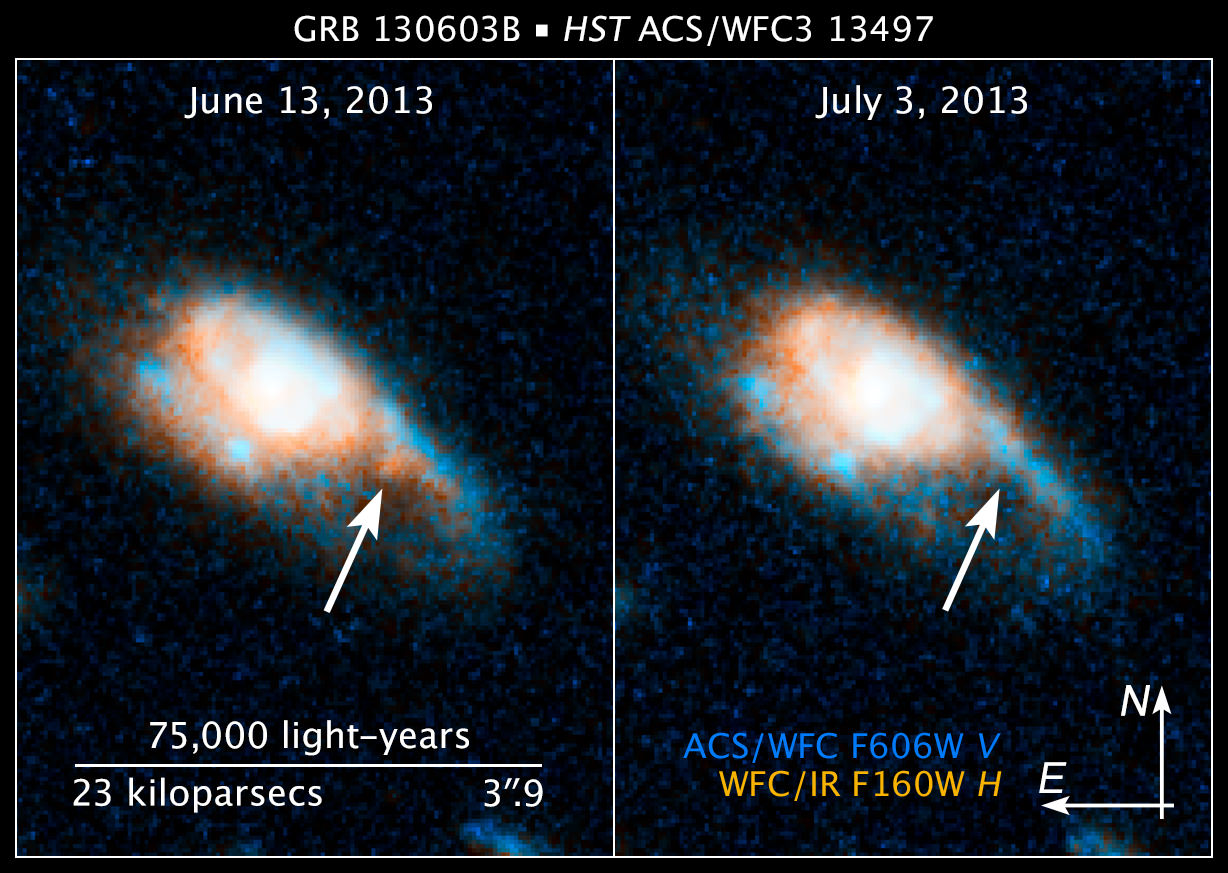

After running multiple calculations, the results show that all misaligned disks tear. Watch tearing in action below:

In most cases this leads to direct accretion onto the binary.

“The gravitational torques from the binary are capable of overpowering the internal communication in the gas disc (by pressure and viscosity),” explains Nixon. “This allows gas rings to be torn off, which can then be accreted much faster.”

Such tearing can produce accretion rates that are 10,000 times faster than if the exact same disk were aligned.

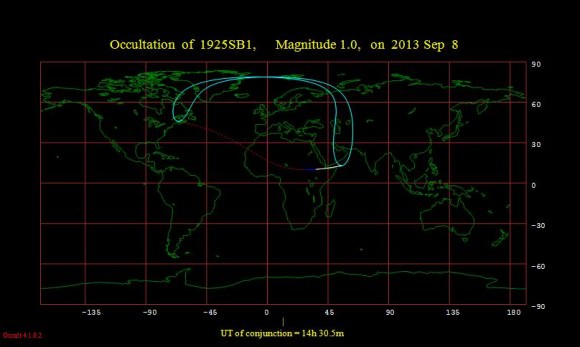

In all cases the gas will dynamically interact with the binary. If it is not accreted directly onto the black hole, it will be kicked out to large radii. This will cause observable signatures in the form of shocks or star formation. Future observing campaigns will look for these signatures.

In the meantime, Nixon et al. plan to continue their simulations by studying the effects of different mass ratios and eccentricities. By slowly making their models more complicated, the team will be able to better mimic reality.

Quick interjection: I love the simplicity of this analysis. These results provide an understandable mechanism as to how some supermassive black holes may have formed.

While these results are interesting alone – based on that sheer curiosity that drives the discipline of astronomy forward – they may also play a more prominent role in our local universe.

Before we know it (please read with a hint of sarcasm as this event will happen in 4 billion years) we will collide with the Andromeda galaxy. This rather boring event will lead to zero stellar collisions and a single black hole collision – as the two supermassive black holes will form a binary pair and then eventually merge.

Without waiting for this spectacular event to occur, we can estimate and model the black hole collision. In 4 billion years the video above may be a pretty good representation of our collision with the Andromeda galaxy.

The results have been published in the Astrophysical Journal Letters (preprint available here). (Link was corrected to correct paper on 8/15/2013).