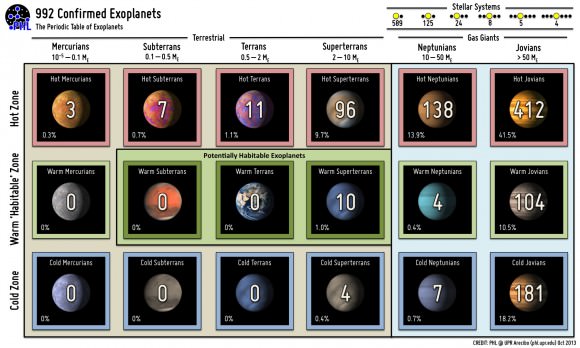

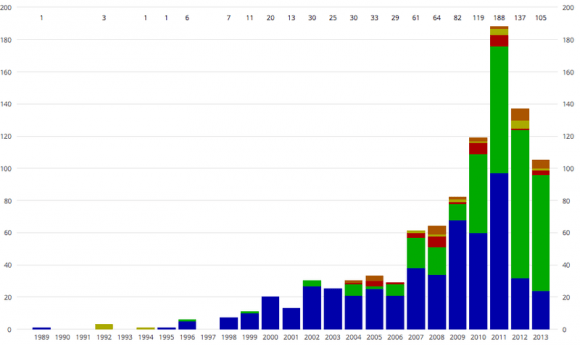

A quiet milestone in modern astronomy may soon come to pass. As of today, The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopedia lists a current tally of 998 extrasolar planets across 759 planetary systems. And although various tabulations differ slightly, very soon we should be living in an era where over one thousand exoplanets are known.

The history of exoplanet discovery has paralleled the course of the modern age of astronomy. It’s strange to think that a generation has already grown up over the past two decades in a world where knowledge of extrasolar planets is a given. I remember hearing of the promise of such detections growing up in the 1970’s, as astronomers put the odds at detection of planets beyond our solar system in our lifetime at around 50%.

Sure, there were plenty of false positives long before the first true discovery was made. 70 Ophiuchi was the site of many claims, starting with that of W.S. Jacob of the Madras Observatory way back in 1855. The high proper motion exhibited by Barnard’s Star at six light years distant was also highly scrutinized throughout the 20th century for claims of an unseen companion causing it to wobble. Ironically, Barnard’s Star still hasn’t made it into the pantheon of stars boasting planetary worlds.

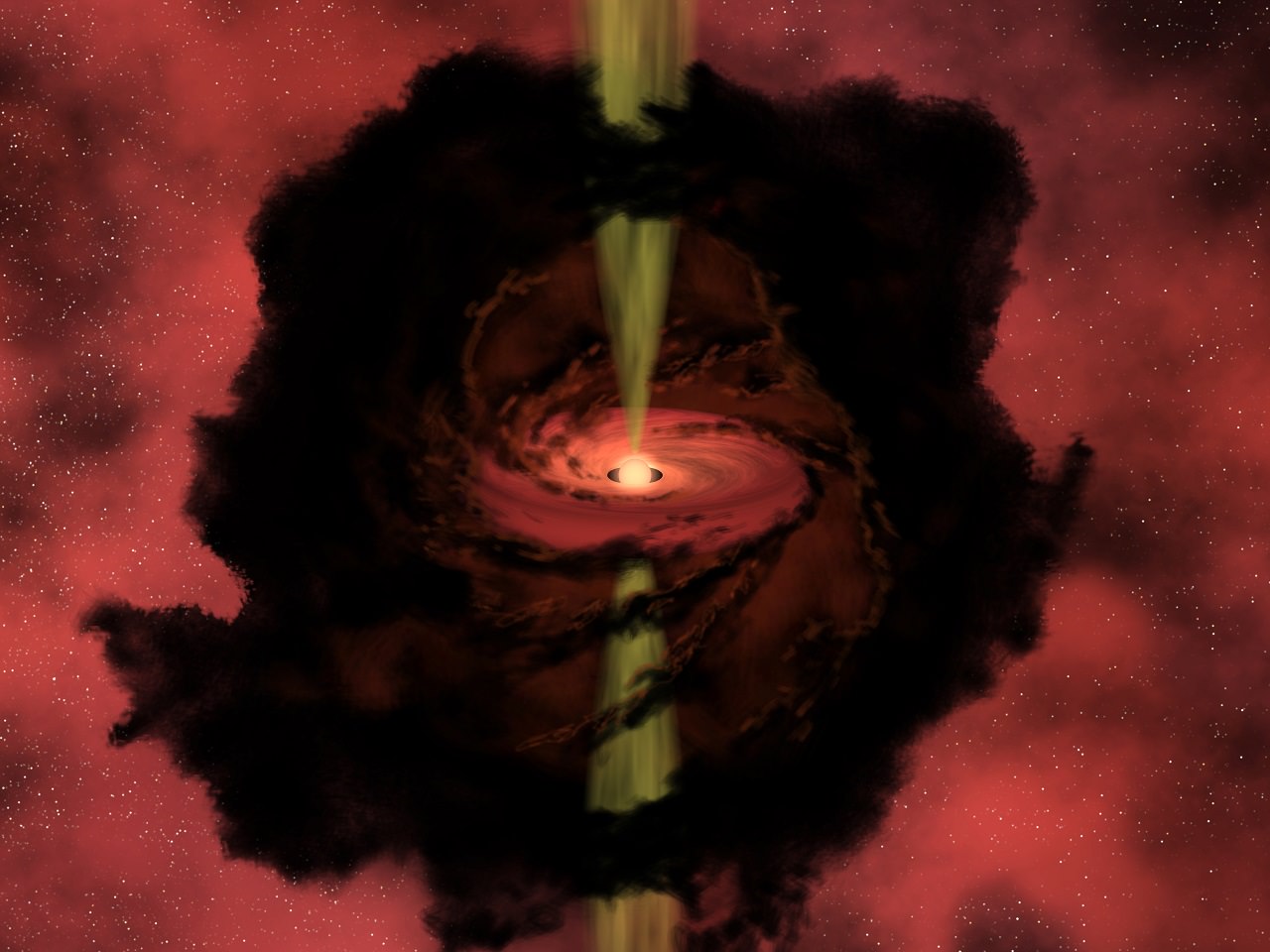

But the first verified claim of an exoplanetary system came from a bizarre and unexpected source: a pulsar known as PSR B1257+12, which was discovered to host two worlds in 1992. This was followed by the first discovery of a world orbiting a main sequence star, 51 Pegasi in 1994. I still remember getting my hands on the latest issue of Astronomy magazine— we got our news, often months later, from actual paper magazines in those days —announcing “Planet Discovered!” on the cover.

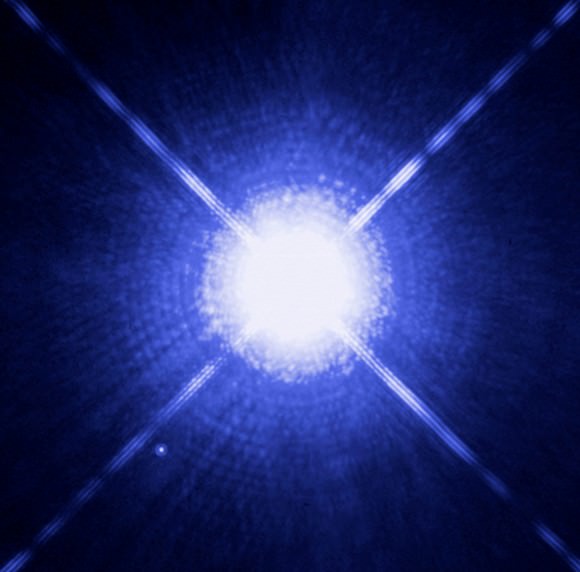

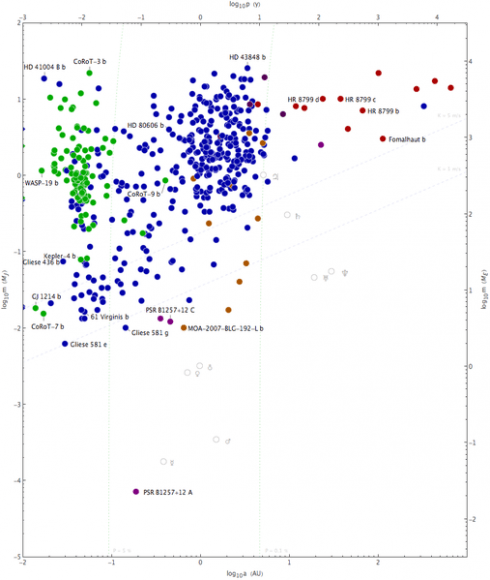

Most methods and techniques used to discover exoplanets rely on either radial velocity or dips in the light output of a star from a transiting world. Both have their utility and drawbacks. Radial velocity looks for shifts in the star’s spectra as an unseen companion tugs it around a common center of mass. Though effective, it can only place a lower limit on the planet’s mass… and it’s biased towards worlds in short orbits. This is one reason that “hot Jupiters” have dominated the early exoplanet catalog: we hadn’t been looking for all that long.

Another method famously employed by surveys such as the Kepler space telescope is the transit detection method. This allows a much more refined estimate of a planet’s mass and orbit, assuming it transits the disk of its host star as seen from our Earthly vantage point in the first place, which most don’t.

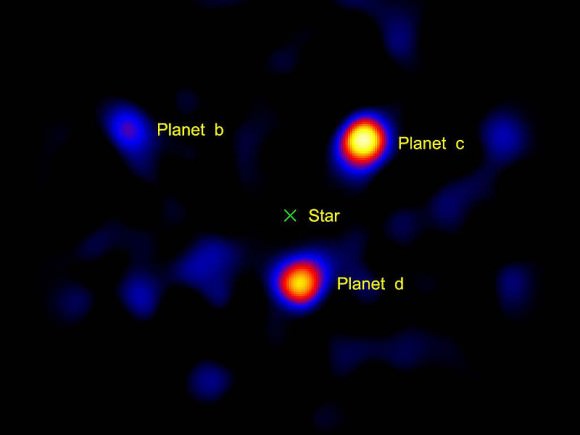

Direct detection via occulting the host star is also coming of age. One of the first exoplanets directly imaged was Fomalhaut b, which can be seen changing positions in its orbit from 2004 to 2006.

Gravitational microlensing has also bared planetary fruit, with surveys such as MOA (Microlensing Observations in Astrophysics) and OGLE (the Optical Gravitational Lensing Experiment) catching brief lensing events as an unseen body passes in front of a background star. Distant free-ranging rogue planets can only be detected via this method.

More exotic techniques also exist, such as relativistic beaming (sounding like something out of Star Trek). Other methods include searches for tiny light variations as an illuminated planet orbits its host star, deformities caused by ellipsoidal variations as massive planets orbit a star, and infrared detections of circumstellar disks. We’re always amazed at the wealth of data that can be teased out of a few dim photons of light.

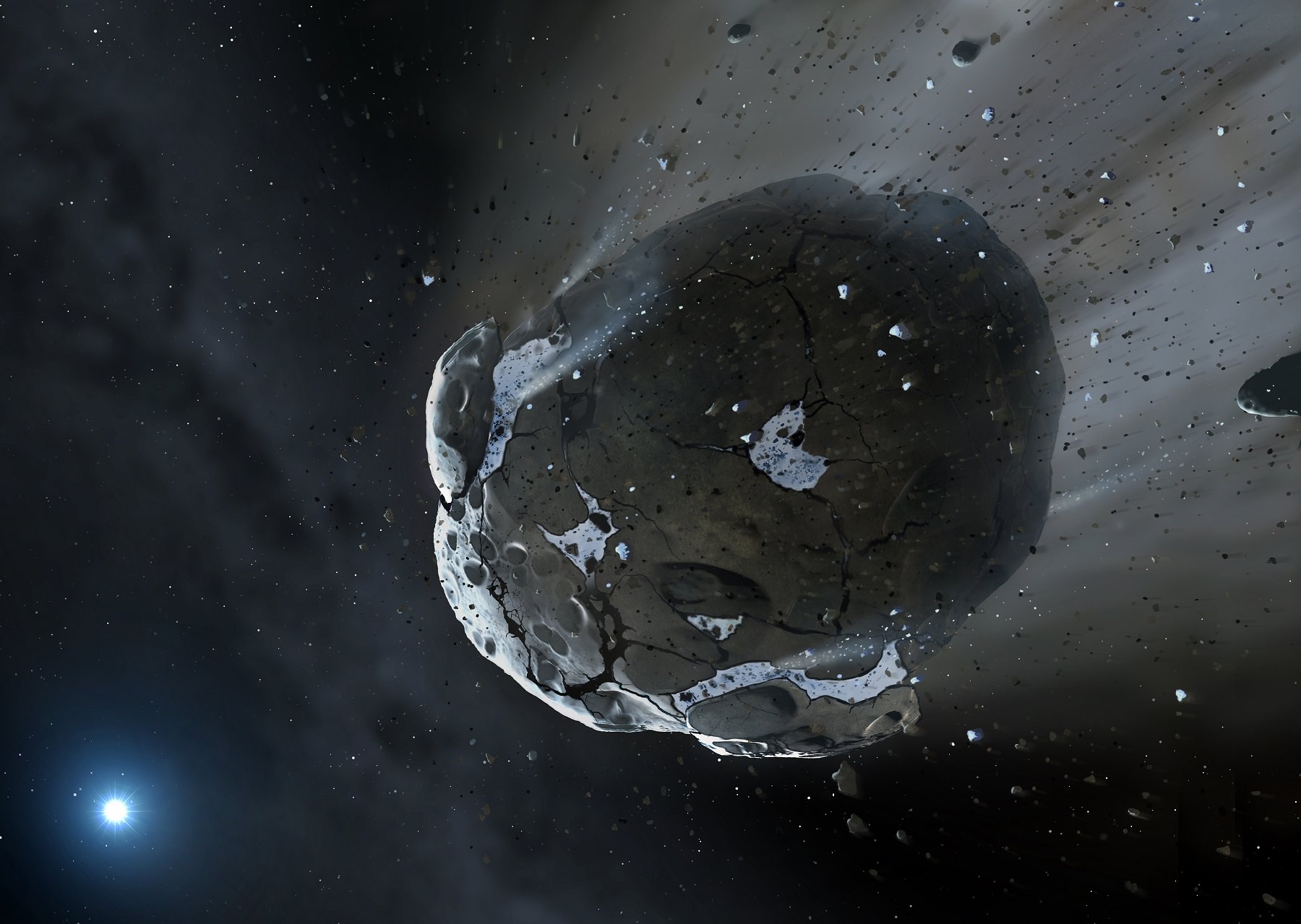

Universe Today has grown up with exoplanet science, from reporting on the hottest, fastest, and other notable “firsts”. A bizarre menagerie of worlds are now known, many of which defy the imagination of science fiction writers of yore. Want a world made of diamond, or one where it rains glass? There’s now an “exoplanet for that”.

Exoplanet news has almost gone from the incredible to the routine, as Tatooine-like worlds orbiting binary stars and systems with worlds in bizarre resonances are announced with increasing frequency.

Exoplanet surveys also have a capacity to peg down that key fp factor in the famous Drake equation, which asks us “what fraction of stars have planets”. It’s been long suspected that stars with planets are the rule rather than the exception, and we’re just now getting hard data to back that assertion up.

Missions, such as NASA’s Kepler space telescope and CNES/ESA CoRoT space telescope have swollen the ranks of extrasolar worlds. Kepler recently ended its career staring off in the direction of the constellations Cygnus, Hercules and Lyra and still has over 3,200 detections awaiting confirmation.

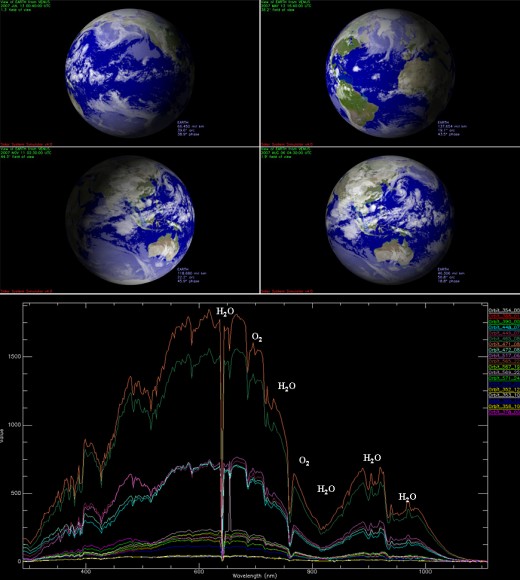

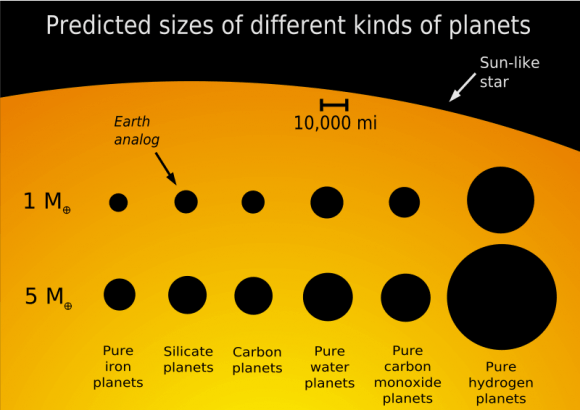

But is a given world Earthlike, or just Earth-sized? That’s the Holy Grail of modern exoplanet detection: an Earth-sized world orbiting in a star’s habitable zone. We’re cautious every time the latest “Earth-twin” makes its way into the headlines. From the perspective of an intergalactic astronomer, Venus in our own solar system might appear to fit the bill, though I wouldn’t bank the construction of an interstellar ark on it and head there just yet.

Exoplanet science has definitely come of age, allowing us to finally begin characterization of solar systems and give us some insight into solar system formation.

But perhaps what will be the most enduring legacy is what the discovery of extrasolar planets tells us about ourselves. How common (or rare) is the Earth? How typical is the story of our solar system? If the “first 1,000” are any indication, we strongly suspect that terrestrial planets come in enough distinct varieties or ”flavors” to make Baskin Robbins envious.

And the future of exoplanet science looks bright indeed. One proposed mission, known as the Fast INfrared Exoplanet Spectroscopy Survey Explorer, or FINESSE, would target exoplanet atmospheres, if given the go ahead for a 2017 launch. Another proposal, known as the Wide Field Infrared Survey Telescope, or WFIRST, would search for microlensing events starting in 2023. A mission that scientists would love to fly that always seems to be shelved is known as the Terrestrial Planet Finder.

But the exoplanet hunting mission that’s closest to launch is the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, or TESS. Unlike Kepler, which stares at a single patch of sky, TESS will be an all-sky survey looking at a half million stars.

We’re also just approaching an era where spectroscopy may allow us to detect exomoons and the chemistry taking place on these far off exoworlds. An example of an exciting discovery would be the detection of a chemical such as chlorophyll, a chemical that we know on Earth only exists as the result of life. But what a tantalizing discovery a blip on a graph would be, when what we humans really want to see is the vista of those far-flung alien forests!

Such is the exciting era we live in. Congratulations, humanity, on detecting 1,000 exoplanets… here’s to a thousand more!