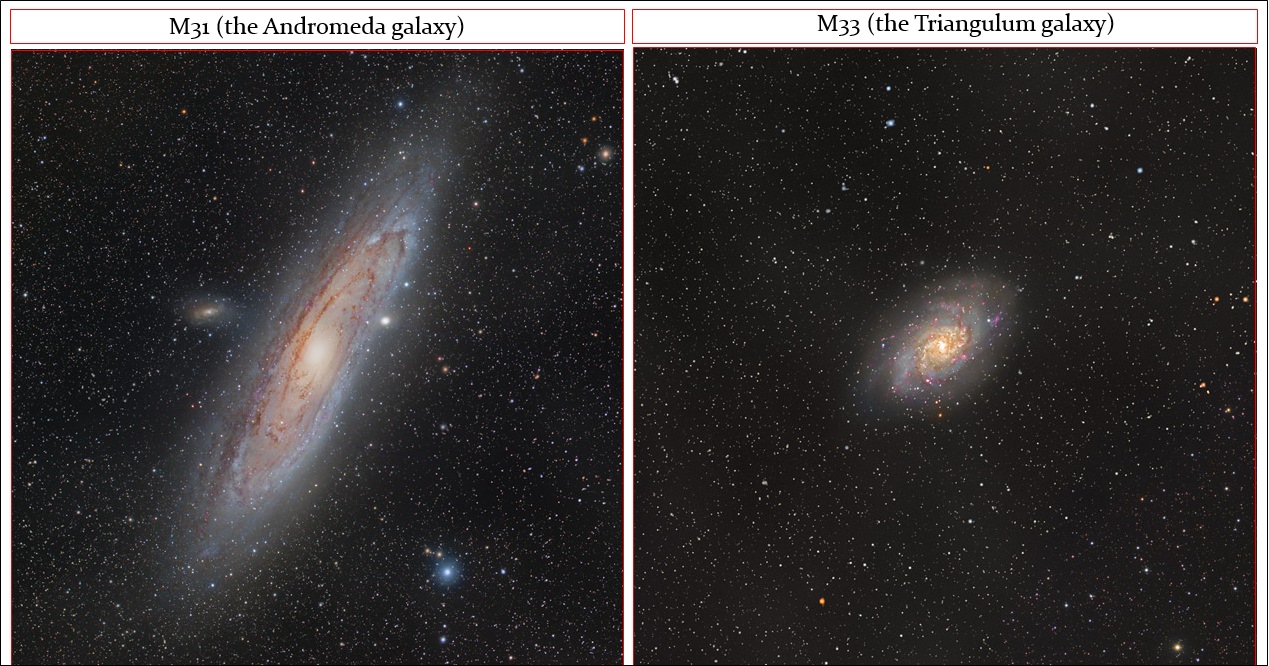

M31 and M33 are two of the nearest spiral galaxies, and can form the basis for determining distances to more remote spiral galaxies and constraining the expansion rate of the Universe (the Hubble constant). Hence the relevance and importance of several new studies that employed near-infrared data to establish solid distances for M31 (Andromeda) and M33 (Triangulum) (e.g., Gieren et al. 2013), and aimed to reduce existing uncertainties tied to the fundamental parameters for those galaxies. Indeed, reliable distances for M31 and M33 are particularly important in light of the new Hubble constant estimate from the Planck satellite, which is offset relative to certain other results, and that difference hinders efforts to ascertain the nature of dark energy (the mysterious force theorized as causing the Universe’s accelerated expansion).

Gieren et al. remarked that, “a number of new distance determinations to M33 … span a surprisingly large interval … which is a cause of serious concern. As the second-nearest spiral galaxy, an accurate determination of [M33’s] distance is a crucial step in the process of building the cosmic distance ladder.” Concerning M31, Riess et al. 2012 likewise remarked that “M31, the nearest analogue of the Milky Way Galaxy, has long provided important clues to understanding the scale of the Universe.“

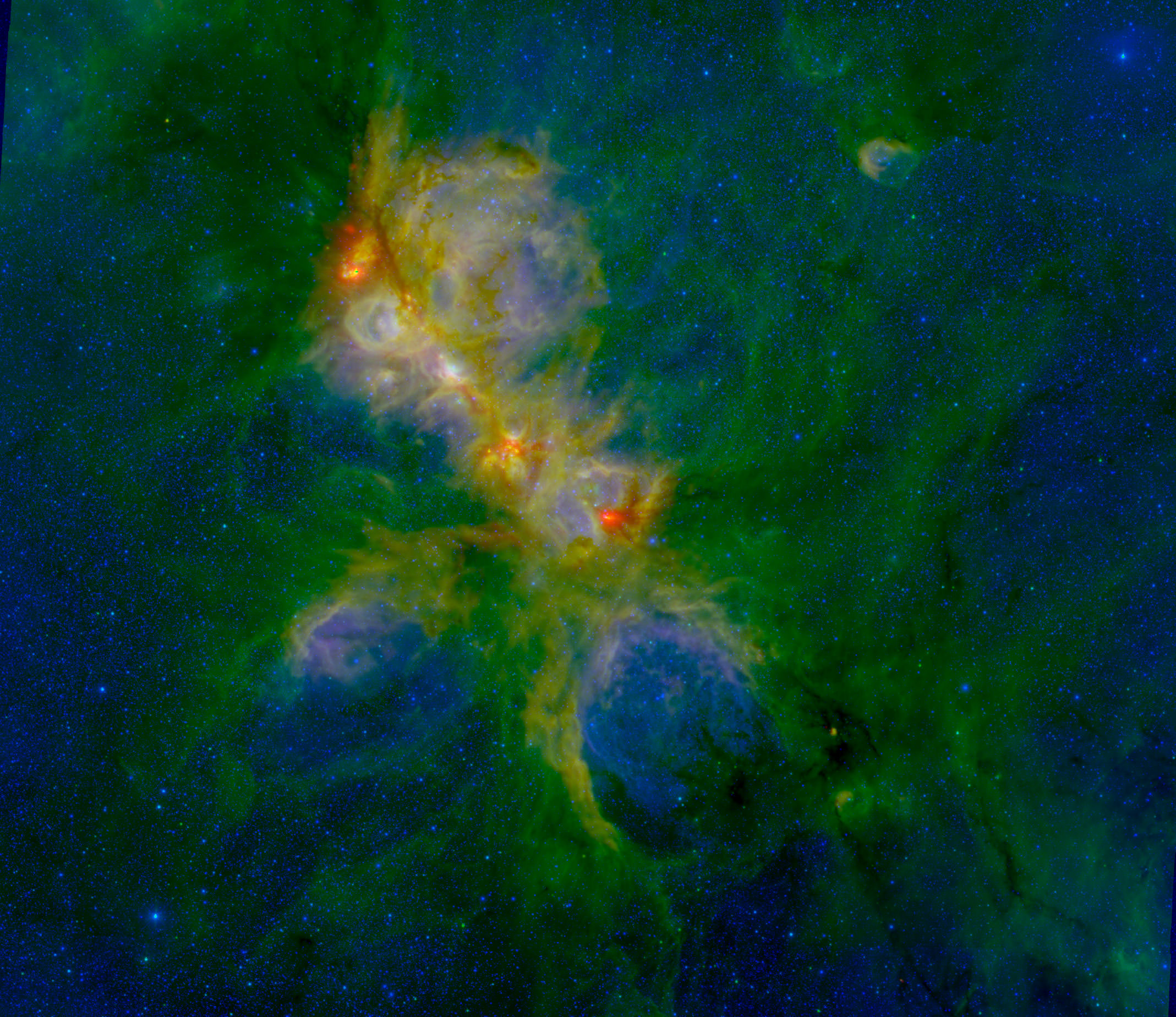

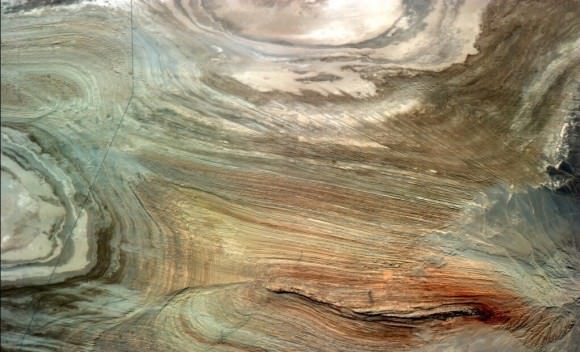

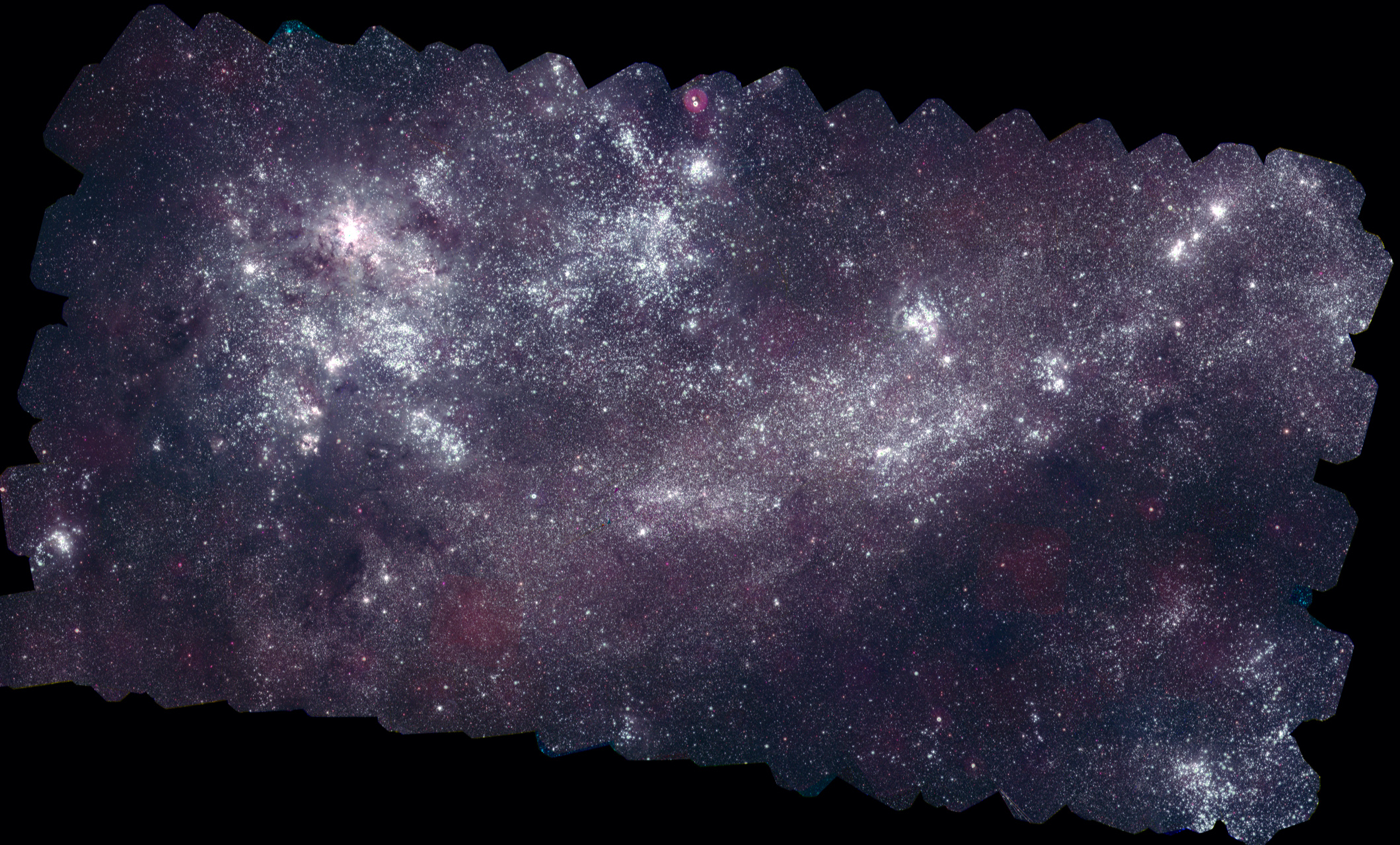

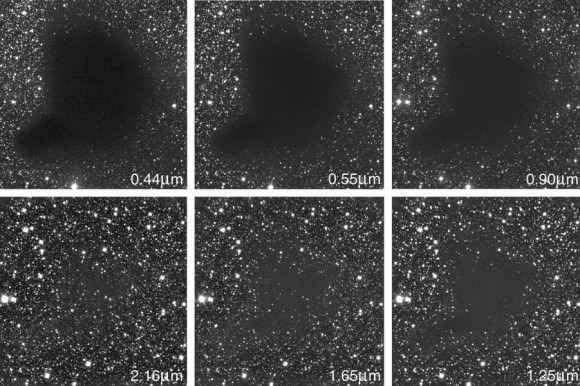

The new Gieren and Riess et al. distances are based on near-infrared observations, which are pertinent because radiation from that part of the electromagnetic spectrum is less sensitive than optical data to absorption by dust located along our sight-line (see the figure below). Properly accounting for the impact of dust is a principal problem in cosmic distance scale work, since it causes targets to appear dimmer. “different assumptions about [dust obscuration] are a prime source for the discrepancies among the various distance determinations for M33.” noted Gieren et al., and the same is true for the distance to M31 (see Riess et al.).

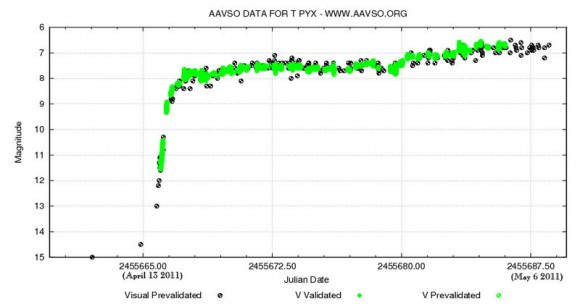

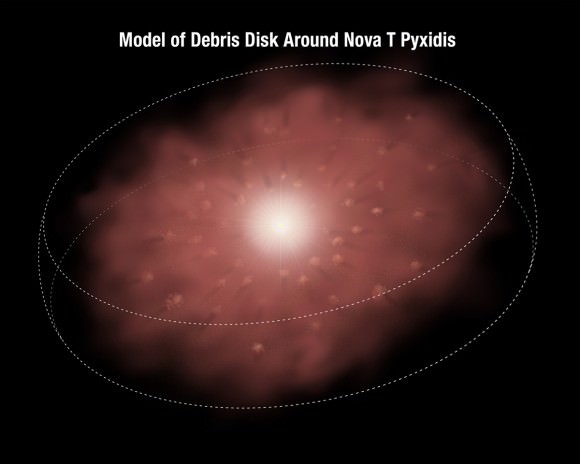

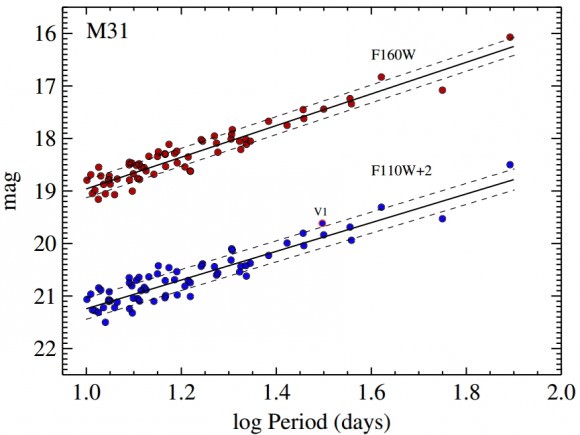

The Gieren and Riess et al. distances to M33 and M31, respectively, were inferred from observations of Cepheids. Cepheids are a class of variable stars that exhibit periodic brightness variations (they pulsate radially). Cepheids can be used as distance indicators because their pulsation period and mean luminosity are correlated. That relationship was discovered by Henrietta Leavitt in the early 1900s. A pseudo period-luminosity relation derived for M31 Cepheids is presented below.

Gieren et al. observed 26 Cepheids in M33 and established a distance of ~2,740,000 lightyears. The team added that, “As the first modern near-infrared Cepheid study [of] M33 since … some 30 years … we consider this work as long overdue …” Astronomers often cite distances to objects in lightyears, which defines the time required for light emitted from the source to reach the observer. Despite the (finite) speed of light being 300,000,000 m/s, the rays must traverse “astronomical” distances. Gazing into space affords one the unique opportunity to peer back in time.

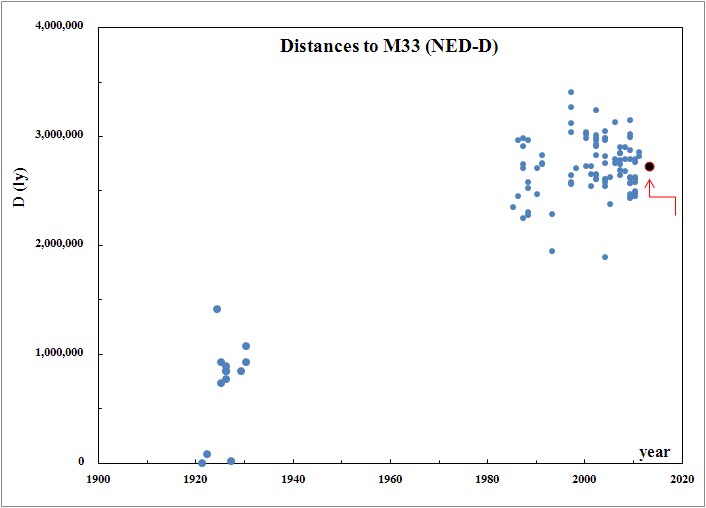

The distances to M33 shown below convey seminal points in the evolution of humanity’s knowledge. The scatter near the 1920s stems partly from a debate concerning whether the Milky Way and the Universe are synonymous. In other words, do galaxies exist beyond the Milky Way? The topic is immortalized in the famed great debate (1920) featuring H. Shapley and H. Curtis (the latter argued for an extragalactic scale). The offset between the pre-1930 and post-1980 data result in part from a nearly two-fold increase in the cosmic distance scale recognized circa 1950 (see also Feast 2000). Also evident is the scatter associated with the post-1980 distances, which merely reinforces the importance of the new high-precision distance estimates.

Riess et al. obtained data for some 70 Cepheids and determined a distance for M31 of ~2,450,000 lightyears. The latter is corroborated by a new study by Contreras Ramos et al. 2013 (d~2,540,000 ly), whose distance estimate relied on data for stars in a M31 globular cluster.

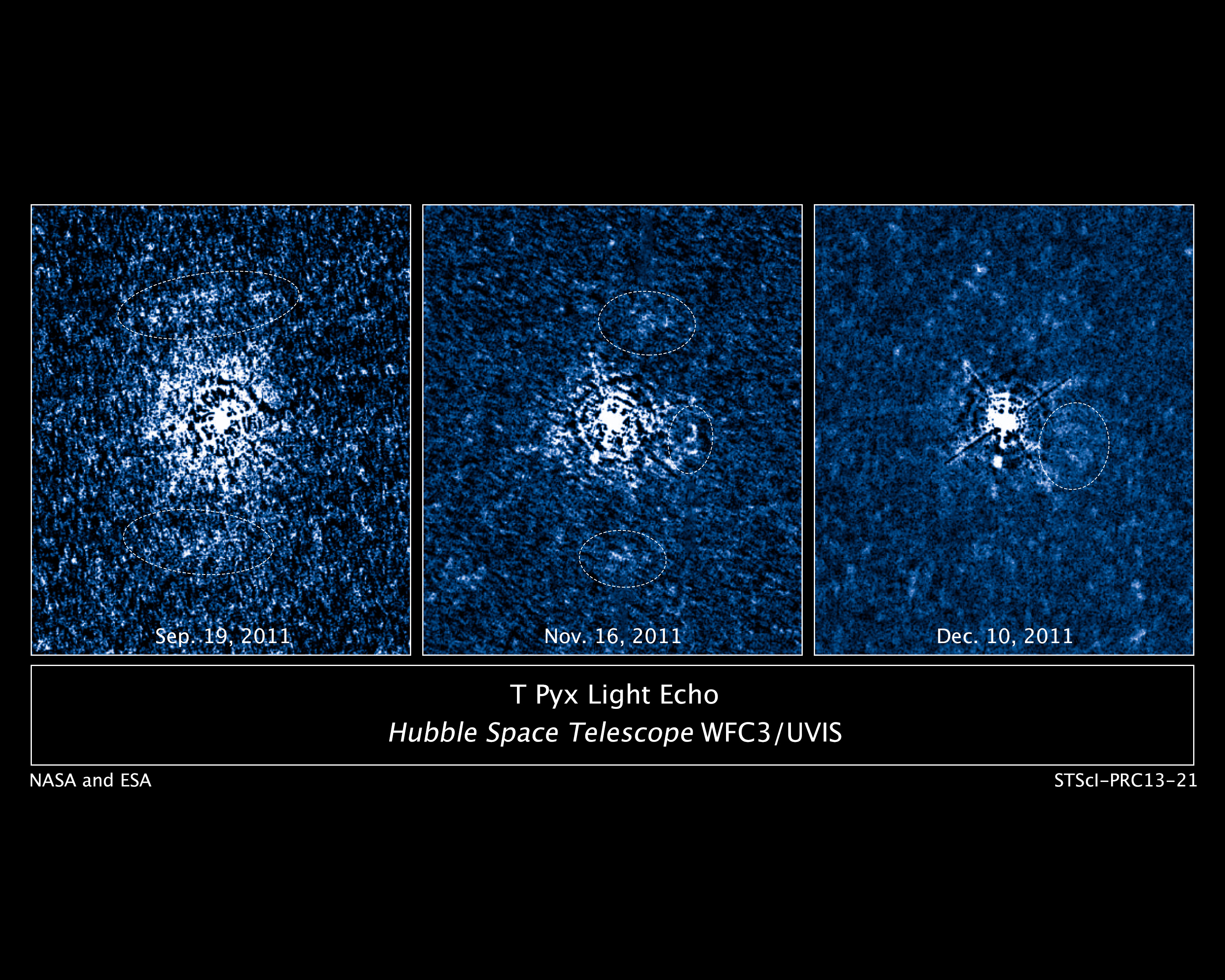

Top-class instruments and telescopes are needed to obtain reliable measurements of stars in galaxies nearly 3,000,000 million lightyears away. Gieren et al. utilized the 8.2-m Very Large Telescope (Yepun) instrument shown below, while Riess and Contreras Ramos et al. analyzed observations from the Hubble Space Telescope. Riess et al. acquired images of M31 via the new Wide-field Camera 3, which replaced the Wide-field and Planetary Camera 2 (“The Camera That Saved Hubble“) during the famed 2009 servicing mission.

The new results mark the culmination of a century’s worth of effort aimed at securing precise distances for our Galaxy’s local spiral kin (M31 and M33). However, the offset between the Planck and certain Cepheid/SN-based determinations of the Hubble constant demands that research continue in order to identify uncertainties associated with the methods.

The Gieren et al. findings have been accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal (ApJ), and a preprint is available on arXiv. Both the Riess and Contreras Ramos et al. studies are likewise published in ApJ. The interested reader desiring additional information on the cosmic distance scale and Cepheids will find the following resources pertinent: the AAVSO’s article on Delta Cephei (the namesake for the class of Cepheid variables), Freedman & Madore (2010), Tammann & Reindl 2012, Fernie 1969, the NASA/IPAC Extragalactic Database, G. Johnson’s Miss Leavitt’s Stars: The Untold Story of the Woman Who Discovered How to Measure the Universe, D. Fernie’s Setting Sail for the Universe: Astronomers and their Discoveries, Nick Allen’s The Cepheid Distance Scale: A History, D. Turner’s Classical Cepheids After 228 Years of Study, J. Percy’s Understanding Variable Stars.