Signs of life on the Martian surface would still be visible even after bacteria were zapped with a potentially fatal dose of radiation, according to new research — if life ever existed there, of course.

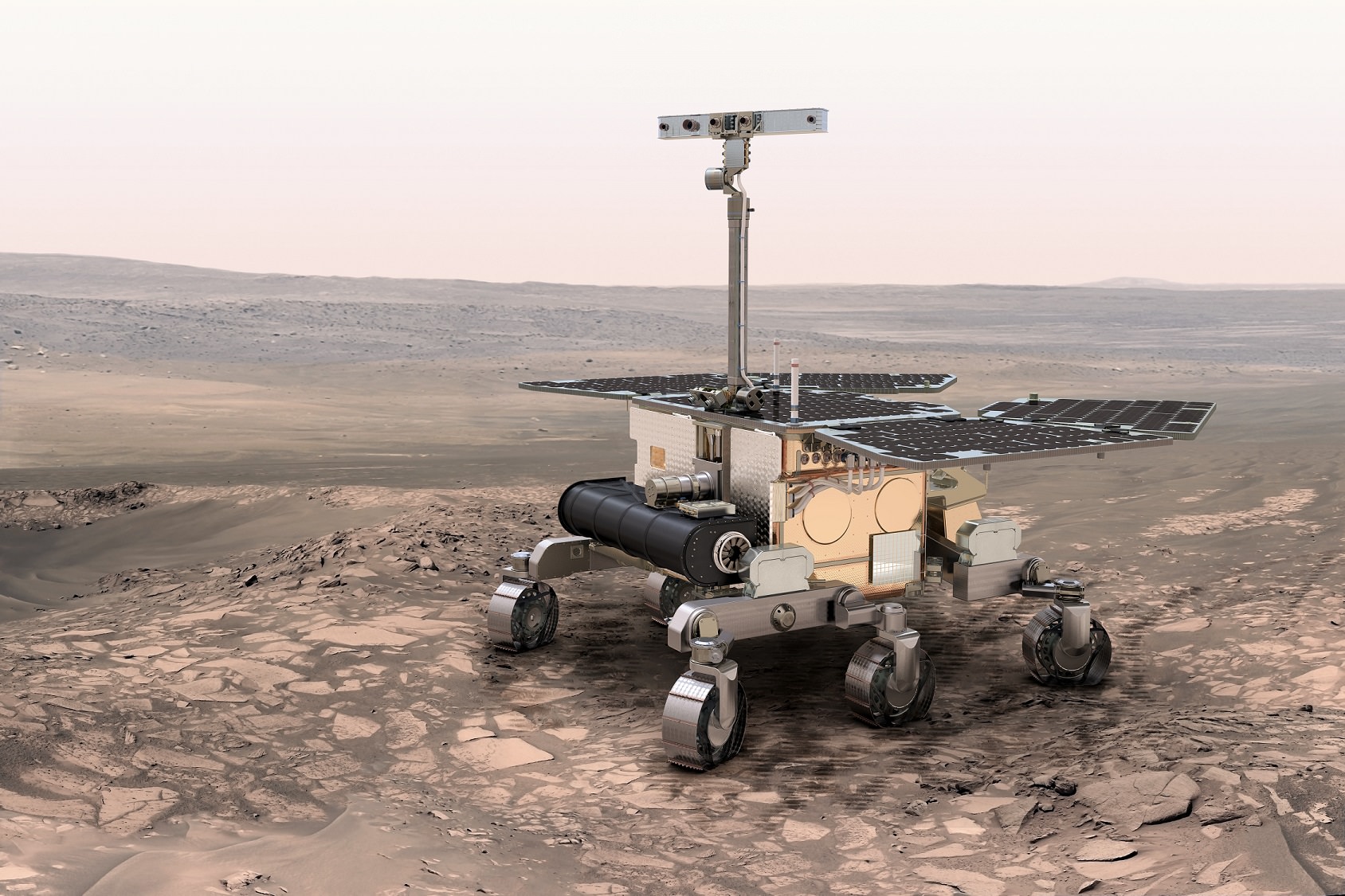

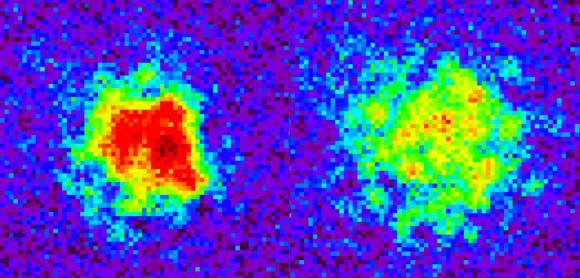

Using “model” bacteria expected to resemble what microbes could look like on the Red Planet, the research team used a Raman spectrometer — an instrument type that the ExoMars rover will carry in 2018 — to see how the signal from the bacteria change as they get exposed to more and more radiation.

The bottom line is the study authors believe the European Space Agency rover’s instrument would be capable of seeing bacteria on Mars — from the past or the present — if the bacteria were there in the first place.

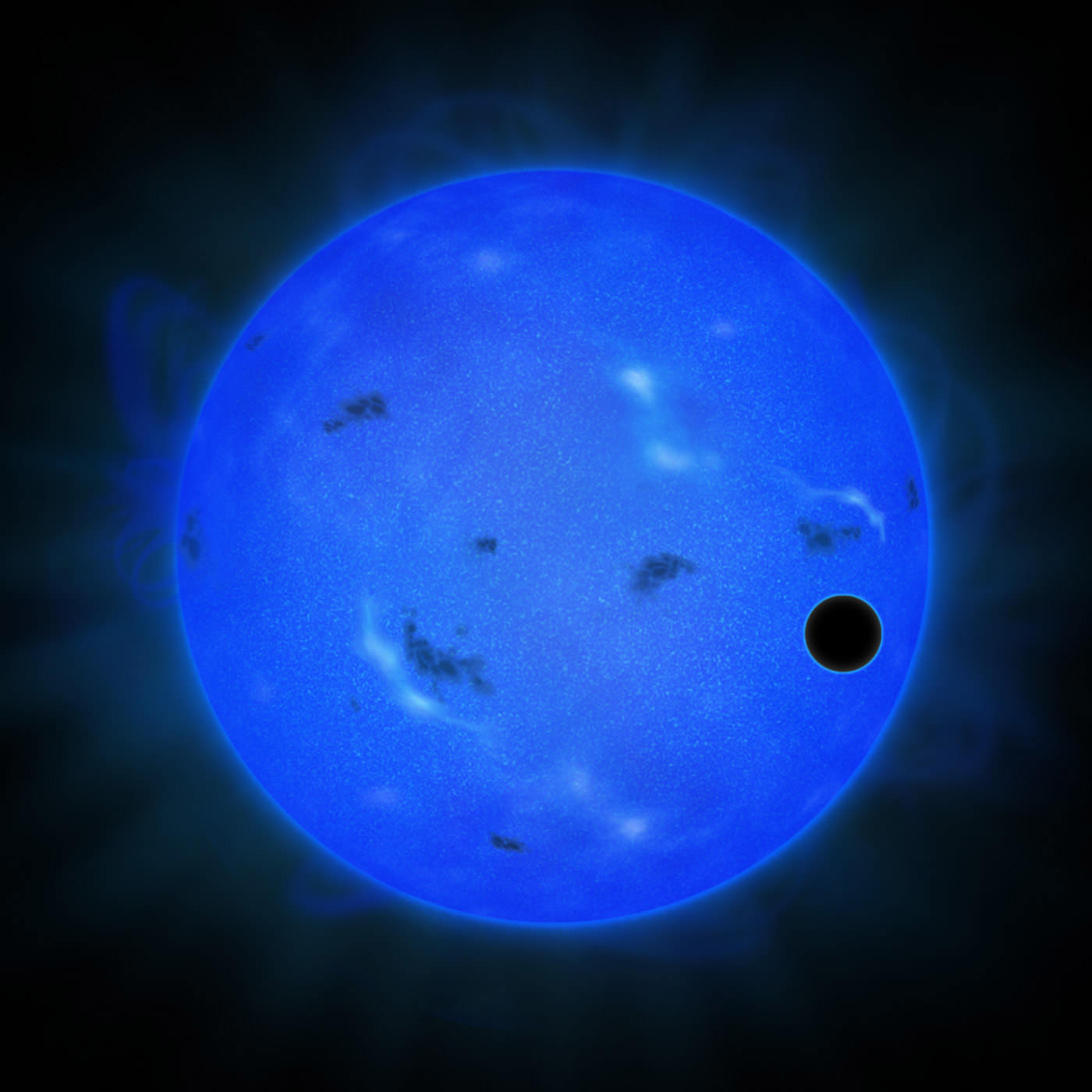

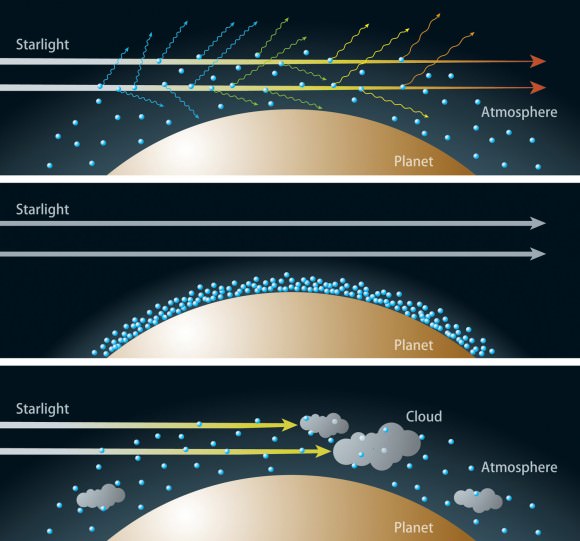

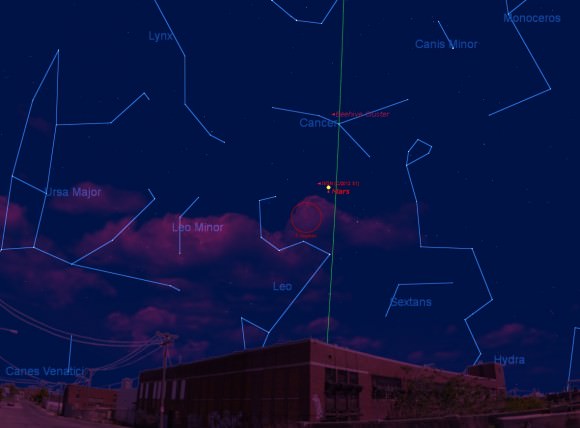

Readings from the NASA Mars Curiosity rover recently found that humans on the surface of Mars would have a higher risk of cancer due to the increased radiation level on the surface. Mars does not have a global magnetic field to deflect radiation from solar flares, nor a thick atmosphere to shelter the surface.

The new study still found the signature of life in these model microbes at 15,000 Gray of radiation, which is thousands of times higher than the radiation dose that would kill a human. At 10 times more, or 150,000 Gray, the signature is erased.

“What we’ve been able to show is how the tell-tale signature of life is erased as the energetic radiation smashes up the cells’ molecules,” stated Lewis Dartnell, an astrobiology researcher at the University of Leicester who led the study.

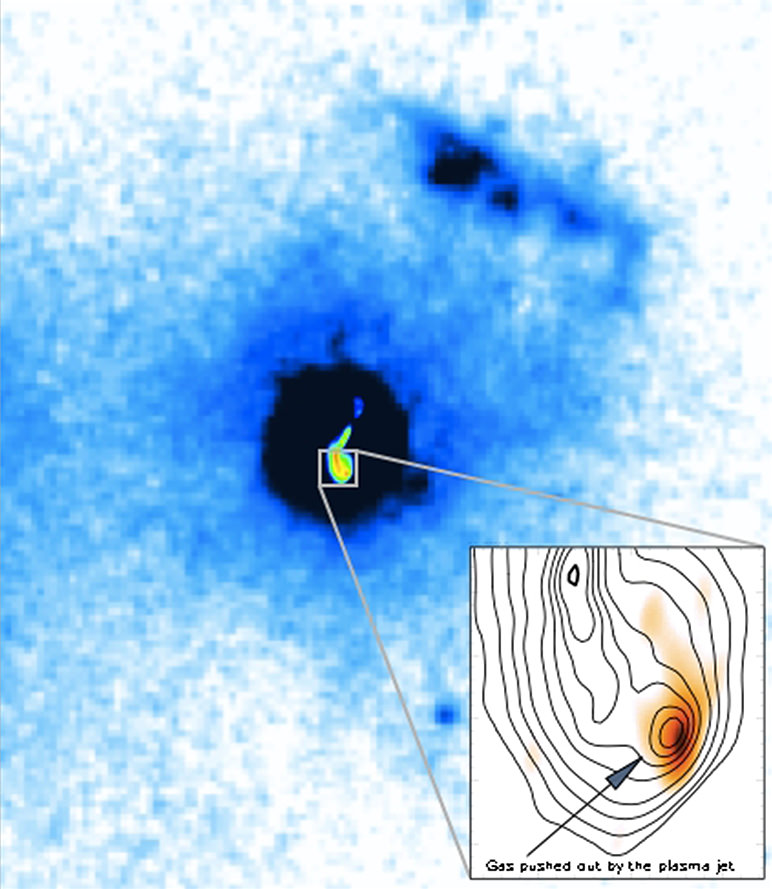

Specifically, the spectrometer detected carotenoid molecules, which can be used to protect a microorganism against difficult conditions in the environment. The research teams stated that these cartenoids have been proposed as “good biosignatures of life” on Mars.

“In this study we’ve used a bacterium with unrivaled resistance to radiation as a model for the type of bacteria we might find signs of on Mars. What we want to explore now is how other signs of life might be distorted or degraded by irradiation,” Dartnell added. “This is crucial work for understanding what signs to look for to detect remnants of ancient life on Mars that has been exposed to the bombardment of cosmic radiation for very long periods of time.”

No one is sure if Mars has life right now on its surface, or ever did in the past. The Mars Curiosity rover is equipped to look at past environmental conditions on the planet, but is not designed to look for life itself.

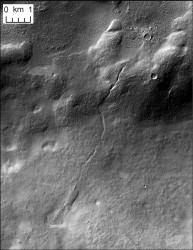

Many scientists believe flowing water existed on the planet, though, based on rock findings from three NASA rovers and the appearance of channels, streams and perhaps even oceans as spotted by orbiting satellites. Some scientists say the atmosphere of Mars was much thicker in the past, but it then dissipated for reasons that are still being investigated. Water, however, does not necessarily point to life.

The research was presented at the European Planetary Science Congress on Monday. Universe Today has reached out to Dartnell to see if the work is peer-reviewed. His website lists several published research articles he wrote on similar topics.

Edit: Dartnell says that research was published in Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry in 2012, and you can read the paper here.

Source: European Planetary Science Congress