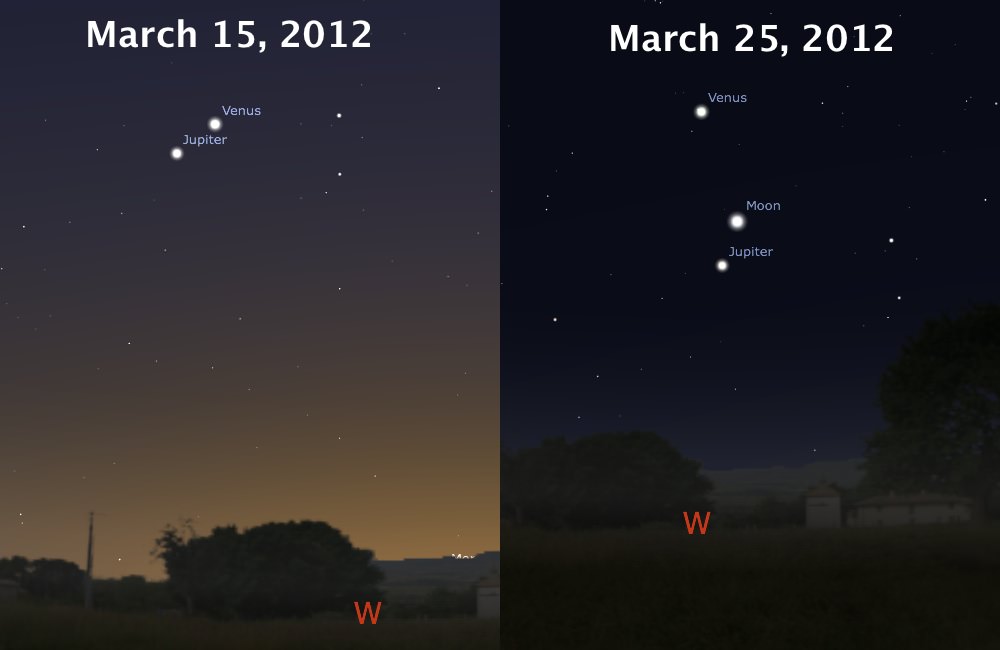

Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! Have you been following the supernova in M95 (R.A. = 10 43 53.76, Decl. = +11 40 17.9)? Who would have ever believed Mars could be considered “light pollution”? Take advantage of darker skies and catch it now! It’s another planetary showdown as the week begins with Jupiter, Venus, the Moon and the Pleiades lighting up the western twilight sky. Right now is an awesome time to study lunar features and to go asteroid hunting! Get out those telescopes and binoculars and I’ll meet you in the back yard…

Monday, March 26 – Need a smile? Then be outside after sunset to check out the awesome solar system show! How often do you see something as cool as the crescent Moon being accompanied by a bright planet like Venus? Or to have another bright planet like Jupiter so nearby? Keep looking, because you can spot the Pleiades just a bit further east. Be sure to point out to your family and friends what a great unaided eye observation can be like!

Tonight the Moon provides an opportunity to view to a very changeable and eventually bright feature on the lunar surface – Proclus. At 28 km in diameter and 2400 meters deep, crater Proclus will appear on the terminator to the west of Mare Crisium’s mountainous border. Depending on your viewing time, it will seem to be about two-thirds shadowed, but the remainder of the crater will shine brilliantly. Proclus has an unusually high albedo, or surface reflectivity, of about 16%. This is uncommon for most lunar features. Watch this area over the next few nights as two rays from the crater widen and lengthen, extending approximately 320 kilometers north and south.

While you’re out, this would also be a good time to have a look at Epsilon Canis Majoris – a great double star. While its companion is quite disparate at roughly magnitude 8, the pair can be easily separated with a small telescope.

Tuesday, March 27 – If you haven’t collected this Lunar Club Challenge crater, tonight will be the perfect opportunity to find the lunar crater named for Joseph Fraunhofer. Return again to the now shallow appearing crater Furnerius. Can you spot the ring at its southern edge? This is crater Fraunhofer – a challenge under these lighting conditions.

Have you noticed the dynamic duo? If not, then you owe it to yourself to take a look at the very close pairing of Spica and Saturn. It’s not often that you can spot a lot of color contrast between celestial objects without optical aid, but blue/white Alpha Virginis and creamy yellow Saturn should be quite noticeable. Have fun!

Speaking of pairs, why not revisit the “Twin Stars” – Castor and Pollux? Separated by not much more than 3 arc seconds, 2.0 magnitude Castor A has a bright sibling – 2.8 magnitude Castor B. The pair is actually a true binary with an orbital period of roughly 500 years. The Castor system contains four lesser members – each main star is a spectroscopic binary. Without Fraunhofer’s discovery of spectra, we would have never known.

Wednesday, March 28 – Born today in 1749, Pierre LaPlace was the mathematician who invented the metric system and the nebular hypothesis for the origin of the solar system. Also born on this day in 1693 was James Bradley, an excellent astrometrist who discovered the aberration of starlight (1729) and the nutation of the Earth. And, in 1802, Heinrich W. Olbers discovered the second asteroid, Pallas, in the constellation Virgo while making observations of the position of Ceres, which had only been discovered fifteen months earlier. Five years later on this same date in 1807, Vesta – the brightest asteroid – was discovered by Olbers in Virgo, making it the fourth such object found.

So, are you ready to go asteroid hunting? To capture asteroid Pallas, you’re going to have to stay up late or get up early, because it’s located right on the ecliptic just west of the circlet of Pisces and running ahead of the rising Sun. Its position will be roughly RA 23h 1m 37s – Dec 11°34’44”. But it does have one thing in its favor – it should be brighter than magnitude 5, so it will be an easy binocular object! Now for Ceres… At close to magnitude 3, it’s so bright you could spot it without optical aid! Tonight it will be visible just after the Sun sets about a handspan southwest of Saturn at roughly RA 2h 18m 43s – Dec 5°49’38”. It certainly makes a pretty picture with the Moon so nearby, too! Last, but not least, is Vesta. Also super-bright, and probably close to magnitude 4, you’ll find Olbers study scooting along the eastern edge of the asterism that denotes the constellation of Capricornus. Its position is roughly RA 21h 39m 21s – Dec 20°35’25”. Remember that time plays an important role in an asteroid’s exact position, and so does your observing location. Be sure to check the resources for planetarium programs or on-line generators that will give you specific information… and have fun!

Tonight’s outstanding lunar features are two craters that you simply can’t miss – Aristotle and Eudoxus. Located to the north, this pair will be highly prominent in binoculars as well as telescopes. The northernmost – Aristotle – was named for the great philosopher and has an expanse of 87 kilometers. Its deep, rugged walls show a wealth of detail at high power, including two small interior peaks. Companion crater Eudoxus, to the south, spans 67 kilometers and offers equally rugged detail.

Thursday, March 29 – Today celebrates the first flyby of Mercury by Mariner 10 in 1974. Mariner 10 was unique. It was the first spacecraft to use a gravity assist from the planet Venus to help it travel on to Mercury. Due to the geometry of its orbit, it was only able to study half the surface, but its 2800 photographs gave us the knowledge that Mercury looks similar to our Moon, has an iron-rich core, a magnetic field, and a very thin atmosphere. Right now Mercury is running ahead of the rising Sun just south of the circlet of Pisces.

Tonight the Moon provides a piece of scenic history as we take a more in-depth look at a previous study crater – Albategnius. This huge, hexagonal, mountain-walled plain appears near the terminator about one-third the way north of the south limb. This 135 kilometer wide crater is approximately 14,400 feet deep and its west wall casts a black shadow on the dark floor. Partially filled with lava after creation, Albategnius is a very ancient formation that later became home to several wall-breech craters, such as Klein, which can be seen telescopically on the southwest wall. Albategnius holds more than just the distinction of being a prominent crater tonight – it also holds a place in history. On May 9, 1962 Louis Smullin and Giorgio Fiocco of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) aimed a ruby laser beam toward the Moon’s surface and Albategnius became the first lunar feature to reflect laser light from Earth.

On March 24, 1965 Ranger 9 took a “snapshot” of Albategnius from an altitude of approximately 2500 km. Ranger 9 was designed by NASA for one purpose – to achieve lunar impact trajectory and send back high-resolution photographs and video images of the lunar surface. Ranger 9 carried no other science packages. Its destiny was to simply take pictures right up to the moment of impact. They called it a “hard landing.”

Friday, March 30 – Tonight’s featured lunar crater is located on the south shore of Mare Imbrium right where the Apennine mountain range meets the terminator. At 58 kilometers in diameter and 12,300 feet deep, Eratosthenes is an unmistakable crater. Named after the ancient Greek mathematician, geographer and astronomer Eratosthenes, this splendid crater will display a bright west wall and a black interior hiding its massive crater capped central mountain 3570 meters high! Extending like a tail, an 80 kilometer mountain ridge angles away to its southwest. As beautiful as Eratosthenes appears tonight, it will fade away to almost total obscurity as the Moon approaches full. See if you can spot it again in five days.

Despite the bright waxing moon, we still have a chance to get a view of a sprinkling of faint stars high to the south at skydark. Located less than a finger-width west-northwest of Wezen (Delta Canis Majoris) – 6.5 magnitude NGC 2354 (Right Ascension: 7 : 14.3 – Declination: -25 : 44) is achievable in small scopes. Although richly populated, this open cluster lacks a bright core. This may challenge the eye to see it. Despite the moonlight, about a dozen stars should be visible in smaller scopes, but return on a moonless night to look for faint clumps and chaining among its 50 or so brightest members.

Before you hang up your eyepieces for the night, be sure to check out Mars. Today’s universal date marks Northern Summer, Southern Winter Solstice on the brilliant red planet. Do the polar caps look any different than they did a few weeks ago? How about surface features? Have you spotted any dust storms or changes? Keep watching, because it won’t be long before Mars is gone!

Saturday, March 31 – Tonight would be a terrific opportunity to study under-rated crater Bullialdus. Located close to the center of Mare Nubium, even binoculars can make out Bullialdus when near the terminator. If you’re scoping – power up – this one is fun! Very similar to Copernicus, Bullialdus’ has thick, terraced walls and a central peak. If you examine the area around it carefully, you can note it is a much newer crater than shallow Lubiniezsky to the north and almost non-existent Kies to the south. On Bullialdus’ southern flank, it’s easy to make out its A and B craterlets, as well as the interesting little Koenig to the southwest.

Today in 1966, Luna 10 was on its way to the Moon. The unmanned, battery powered Luna 10 was a USSR triumph. Launched from an Earth orbiting platform, the probe became the first to successfully orbit another solar system body. During its 460 orbits, it recorded infrared emissions, gamma rays, and analyzed lunar composition. It monitored the Moon’s radiation conditions – measuring the belts and discovering what eventually would be referred to as “mascons” – mass concentrations below maria surfaces which magnetically affect orbiting bodies. Do you remember any areas we’ve studied so far that contain a mascon?

While the Moon will be nearly overpowering tonight, let’s take a look at a pair of orbiting bodies as we head for Kappa Puppis – a bright double of near equal magnitudes. This one is well suited to northern observers with small telescopes. For the southern observer, try your hand at Sigma Puppis. At magnitude 3, this bright orange star holds a wide separation from its white 8.5 magnitude companion. Sigma’s B star is a curiosity, because at a distance of 180 light-years it would be about the same brightness as our own Sun placed at that distance!

Sunday, April 1 – Today in 1960, the first weather satellite – Tiros 1 – was launched. While today we think of these types of satellites as commonplace, the Television InfraRed Observation Satellite was quite an achievement. Weighing in at 120 kilograms, it contained two cameras and magnetic tape recorders – along with an on-board battery supply and 9200 solar cells to keep them charged. While it only operated successfully for 78 days, for the first time ever we were able to see the face of the Earth’s changing weather.

Tonight we’ll have the opportunity to look for a lunar feature named for Urbain Leverrier. To find it, start with the C-shape of Sinus Iridum. Imagine that Iridum is a mirror focusing light – this will lead your eye to crater Helicon. The slightly smaller crater southeast of Helicon is Leverrier. Be sure to power up to capture the splendid north-south oriented ridge which flows lunar east.

Now check out the close triangulation of Regulus, Mars and Algieba. This splendid triangulation of stars and a planet are only separated by a few degrees and make for a splendid sight!

Until next week? Ask for the Moon… But keep on reaching for the stars!