[/caption]

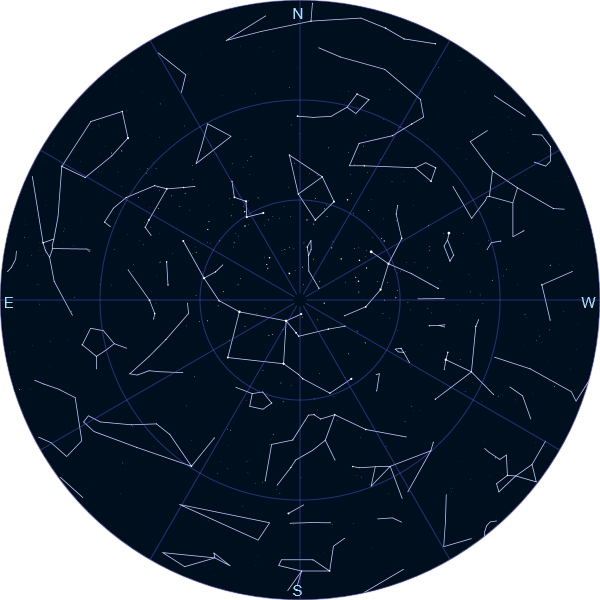

Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! As the Moon fades away, dark sky studies return and so do we as we take a look at a great collection of nebulae this week and expand your Herschel studies. Get out your binoculars and telescopes, because here’s what’s up!

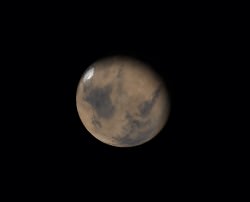

Sunday, February 12 – Today is the anniversary (2001) of NEAR landing on asteroid Eros. The Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous (NEAR) mission was the first to ever orbit an asteroid, successfully sending back thousands of images. Although it was not designed to land on Eros, it survived the low speed impact and continued to send back data. Would you like to view Eros for yourself? It will be visible a few hours after sky dark. At somewhere between magnitude 11 and 12, Eros will require at least a mid-sized telescope, but is very viewable to both hemispheres along the Hydra/Crater border… and about a handspan southwest of Mars! Be sure to check resources for a planetarium program or on-line service which will give you a precise location for your time and area.

Tonight we’ll continue onward with our studies of Lepus as we head for two more of the coveted Herschel 400 objects. Our hop starts with beautiful Gamma and NGC 2073. Located less than a fingerwidth northeast of Gamma (RA 05 45 53.90 Dec -21 59 59.0), NGC 2073 might be magnitude 12.4, but its small size makes it anything but easy. Even if it does have some highly studied molecular cloud structure, be prepared to see nothing but a tiny, egg-shaped contrast change in the elliptical Herschel 241.

Continue northeast a little more than 2 degrees (RA 05 54 52.30 Dec -20 05 03.0) to encounter Herschel 225 – NGC 2124. Although it is slightly fainter, we are at least picking up something with more recognizable structure. Oriented north/south, Herschel 225 is an inclined spiral with a bright nucleus. Set in a wonderfully rich star field, it’s difficult to spot at first with low power, but its slim structure holds up well to magnification. This one is really a pleasure.

Monday, February 13 – Today is the birthday of J.L.E. Dreyer. Born in 1852, the Danish-Irish Dreyer came to fame as the astronomer who compiled the New General Catalogue (NGC) published in 1878. Even with a wealth of astronomical catalogs to chose from, the NGC objects and Dreyer’s abbreviated list of descriptions still remain the most widely used today.

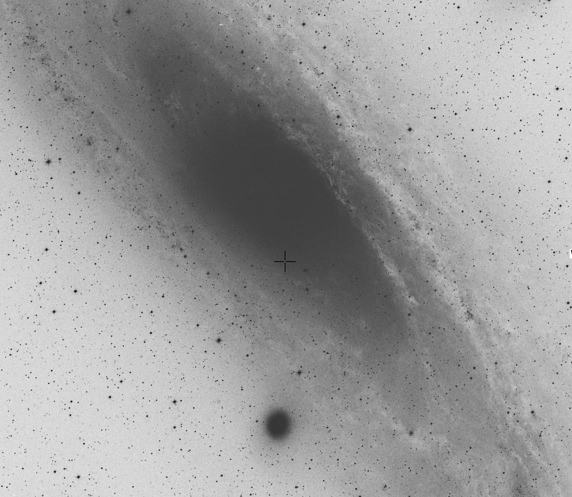

Tonight let’s make Dreyer proud as we finish up our Herschel 400 studies for Herschel 267. At magnitude 13, NGC 2076 (Right Ascension: 5 : 46.8 – Declination: -16 : 46 ) is a lot less forgiving of scope size and sky conditions than some galaxies, but if aperture and sky cooperate, you are in for a real treat! Although it is fairly small and somewhat faint, NGC 2076 is an edge-on that will show indications of a dark dustlane across its brighter nucleus, when using aversion. The lane itself has been highly studied for dust extinction and star forming properties and as recently as 2003 a supernova event was reported just south of the nucleus.

Now let’s drop south about one degree and pick up Herschel 270! Far brighter at magnitude 11.9, don’t let the ordinary elliptical NGC 2089 (Right Ascension: 5 : 47.8 – Declination: -17 : 36) fool you. What would appear to be a stellar nucleus is indeed stellar. Studies done by AAVSO have shown that the bright point of light is actually a line of sight star. Congratulations on your studies and be sure to write down your Herschel “homework!”

Tuesday, February 14 – Happy Valentine’s Day! Today is the birthday of Fritz Zwicky. Born in 1898, Zwicky was the first astronomer to identify supernovae as a separate class of objects. His insights also proposed the possibility of neutron stars. Among his many achievements, Zwicky also catalogued galaxy clusters and designed jet engines.

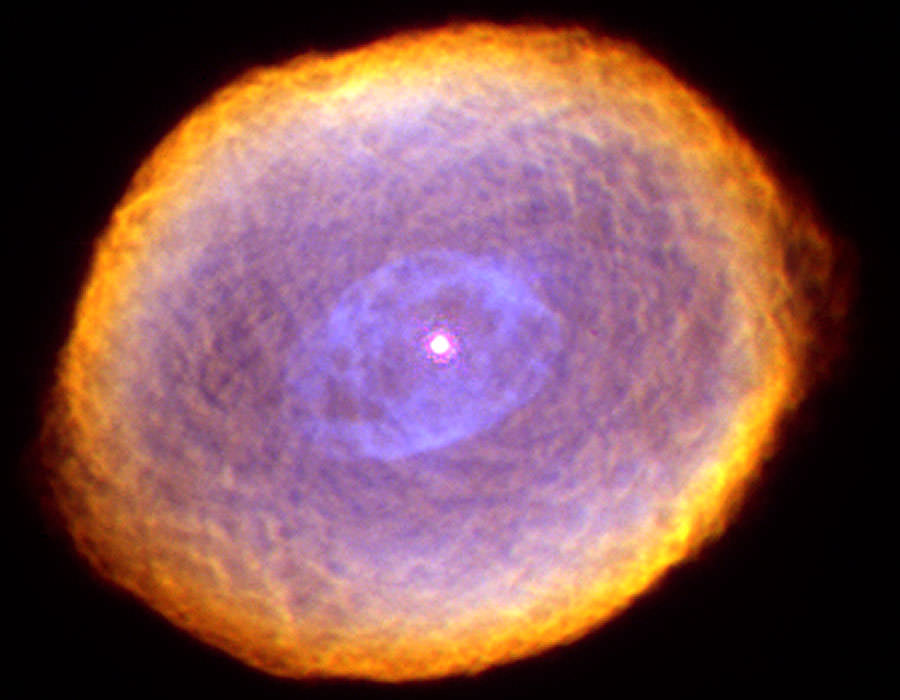

In mythology, Lepus the Hare is hiding in the grass at Orion’s feet. As we have seen, there are many objects of beauty hidden within what seems to be a very ordinary constellation. Before we leave the “Rabbit” for this year, there is one last object that is worthy of attention. If you look to the feet of Orion and the brightest star of Lepus, you will see that they make a triangle in the sky. Tonight we are headed towards the center of that triangle for a singular object – the Spirograph Nebula.

Shown in all its glory through the eye of the Hubble Telescope, the light you see tonight from the IC 408 (Right Ascension: 5 : 17.9 – Declination: -25 : 05) planetary nebula left in the year 7 AD. Its central star, much like our own Sol, was in the final stages of its life at that time, and but a few thousand years earlier was a red giant. As it shed its layers off into about a tenth of a light-year of space, only its superheated core remained – its ultraviolet radiation lighting up the expelled gas. Perhaps in several thousand years the nebula will have faded away, and in several billion years more the central star will have become a white dwarf – a fate that also awaits our own Sun.

At magnitude 11, it is well within reach of a small to mid-size telescope. Like all planetary nebulae, the more magnification – the better the view. The central star is easily seen against a slightly elongated shell and larger telescopes bring an “edge” to this nebula that makes it very worthwhile studying. Spend some quality time with this object. With larger scopes, there is no doubt a texture to this planetary that will delight the eye…and touch the heart!

Wednesday, February 15 – Born on this day in 1564 was the man who fathered modern astronomy – Galileo Galilei. Two and a half centuries ago, he became first scientist to use a telescope for astronomical observation and his first target was the Moon. Just before dawn this morning you will have the opportunity to observe the waning crescent and the tiny crater named for Galileo. Almost central along the terminator and caught near the edge of Oceanus Procellarum, you will see a small, bright ring. This is Reiner Gamma and you will find Galileo just a short hop to the northwest as a tiny, circular crater. What a shame the cartographers did not pick a more vivid feature to name after the great Galileo!

With absence of the Moon in our favor tonight, it’s time to learn the constellation of Monoceros as the skies darken and Orion begins to head west. By using the red giant Betelgeuse, diamond-bright Sirius and the beacon of Procyon, we can see these three stars form a triangle in the sky with Sirius pointing towards the south. The “Unicorn” is not a bright constellation, and most of its stars fall inside this area with its Alpha star almost a handspan south of Procyon.

Using the belt of Orion as a guide, look a handspan east, this is Delta. A fistwidth away to the southeast is Gamma; with Beta about two fingerwidths further along. About a palmwidth southeast of Betelguese is Epsilon. Although this might seem simplistic, knowing these stars will help you find many wonderful objects. Let’s start our journey tonight two fingerwidths northwest of Epsilon… NGC 2186 (Right Ascension: 6 : 12.2 – Declination: +05 : 2) is a triangular open cluster of stars set in a rich field that can be spotted with binoculars and reveals as many as 30 or more stars to even a small telescope. Not only is this a Herschel 400 object that can be spotted with simple equipment, but a highly studied galactic cluster that contains circumstellar discs!

Thursday, February 16 – On this day in 1948, Gerard Kuiper was celebrating his discovery of Miranda – one of Uranus’ moons. Just 42 years earlier on this day, both Kopff and Metcalf were also busy – discovering asteroids! Today is the birthday of Francois Arago. Born in 1786, Arago became the pioneer scientist in the wave nature of light. His achievements were many and he is also credited as the inventor of the polarimeter and other optical devices.

Tonight let’s celebrate Arago’s achievements in polarization as we return again to Epsilon Monocerotis. Our destination is around a fingerwidth east as we seek out another star cluster that has an interesting companion – a nebula!

NGC 2244 (Right Ascension: 6 : 32.4 – Declination: +04 : 52) is a star cluster embroiled in a reflection nebula spanning 55 light-years and most commonly called “The Rosette.” Located about 2500 light-years away, the cluster heats the gas within the nebula to nearly 18,000 degrees Fahrenheit, causing it to emit light in a process similar to that of a fluorescent tube. A huge percentage of this light is hydrogen-alpha, which is scattered back from its dusty shell and becomes polarized.

While you won’t see any red hues in visible light, a large pair of binoculars from a dark sky site can make out a vague nebulosity associated with this open cluster. Even if you can’t, it is still a wonderful cluster of stars crowned by the yellow jewel of 12 Monocerotis. With good seeing, small telescopes can easily spot the broken, patchy wreath of nebulosity around a well-resolved symmetrical concentration of stars. Larger scopes, and those with filters, will make out separate areas of the nebula which also bear their own distinctive NGC labels. No matter how you view it, the entire region is one of the best for winter skies.

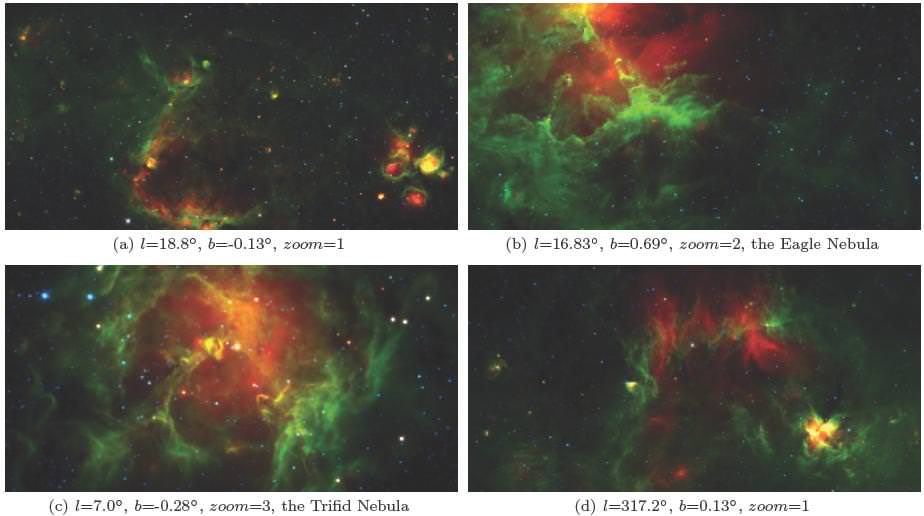

Friday, February 17 – Tonight is a good time for us to go hunting some obscure objects that will require the darkest of skies. Once again, we’ll use our guide star Epsilon and tonight we’ll be heading about three fingerwidths northeast for a vast complex of nebulae and star clusters.

To the unaided eye, 4th magnitude S Monocerotis is easily visible and to small binoculars so are the beginnings of a rich cluster surrounding it. This is NGC 2264 (Right Ascension: 6 : 41.1 – Declination: +09 : 53). Larger binoculars and small telescopes will easily pick out a distinct wedge of stars. This is most commonly known as the “Christmas Tree Cluster,” its name given by Lowell Observatory astronomer Carl Lampland. With its peak pointing due south, this triangular group is believed to be around 2600 light-years away and spans about 20 light-years. Look closely at its brightest star – S Monocerotis is not only a variable, but also has an 8th magnitude companion. The group itself is believed to be almost 2 million years old.

The nebulosity is beyond the reach of a small telescope, but the brightest portion illuminated by one of its stars is the home of the Cone Nebula. Larger telescopes can see a visible V-like thread of nebulosity in this area which completes the outer edge of the dark cone. To the north is a photographic only region known as the Foxfur Nebula, part of a vast complex of nebulae that extends from Gemini to Orion.

Northwest of the complex are several regions of bright nebulae, such as NGC 2247, NGC 2245, IC 446 and IC 2169. Of these regions, the one most suited to the average scope is NGC 2245 (Right Ascension: 6 : 32.7 – Declination: +10 : 10), which is fairly large, but faint, and accompanies an 11th magnitude star. NGC 2247 (Right Ascension: 6 : 33.2 – Declination: +10 : 20) is a circular patch of nebulosity around an 8th magnitude star, and it will appear much like a slight fog. IC 446 is indeed a smile to larger aperture, for it will appear much like a small comet with the nebulosity fanning away to the southwest. IC 2169 is the most difficult of all. Even with a large scope a “hint” is all!

Enjoy your nebula quest…

Saturday, February 18 – On this day in 1930, a young man named Clyde Tombaugh was very busy checking out some photographic search plates taken with the Lowell Observatory’s 13″ telescope. His reward? The discovery of Pluto! And just where is the planet that isn’t a planet any more? You can find it before dawn! The little rascal is hiding out in a very stellar field just east of M25 and a couple of degrees northwest of the slender crescent Moon. How do you know which faint “star” is Pluto? Well, if you set a computerized telescope to RA 18h 24m 59s – Dec 19°18’44”, it will be precisely in the center of the field if you are perfectly polar aligned. If you are using a manual telescope, you will need to sketch the field and return over a period of several days to see which “star” moves. It would be a great lesson – since early astronomers did it that way!

This evening let us return to the realm of binoculars and small telescopes as we head now for Beta Monocerotis and a little more than a fingerwidth north for NGC 2232 (Right Ascension: 6 : 26.6 – Declination: -04 : 45). This wonderful collection of stars sparkles with chains and various magnitudes – the brightest of which is 5th magnitude 10 Monocerotis. Well resolved with a small telescope, its apparent size of about a full moon-width makes it a true delight and it can even be spotted unaided from a dark sky site. Be sure to note it, because it is on many open cluster study lists.

Now head back to Beta and about the same distance west for Class D cluster NGC 2215 (Right Ascension: 6 : 21.0 – Declination: -07 : 17). At magnitude 8, it is still within the realm of binoculars, but will look like a small fuzzy patch beyond resolution. Try this one with a telescope! Set in a rich field, the compressed area of near equal magnitude stars isn’t the most colorful in the sky, but you can add another to your Herschel hits!

Until next week, may all your journeys be at light speed!