[/caption]

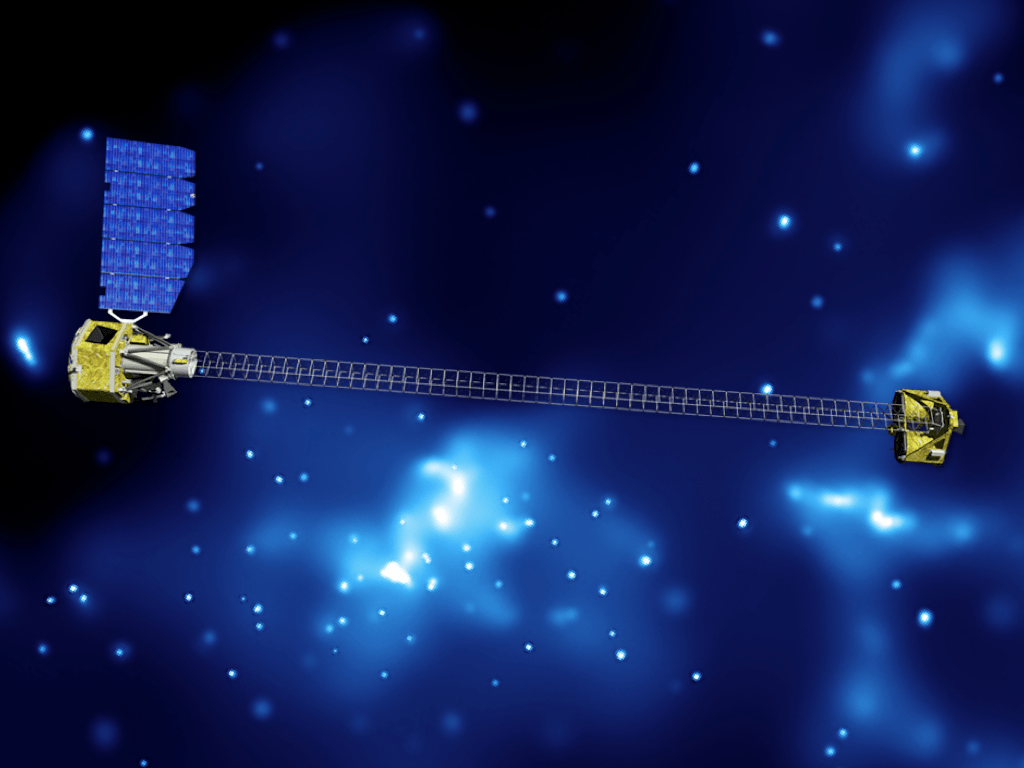

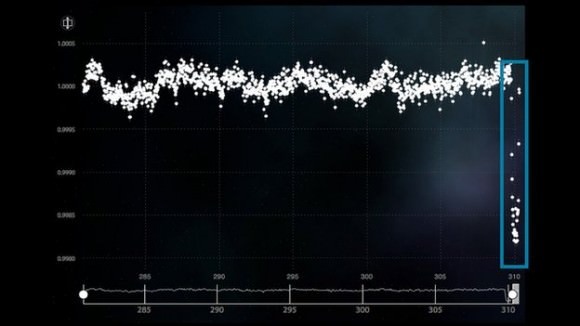

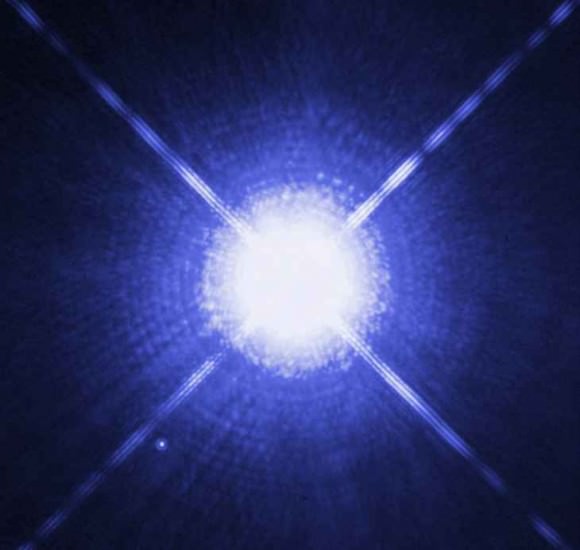

On March 14, NASA will launch the Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array or NuSTAR. This is the first time a telescope will focus on high energy X-rays, effectively opening up the sky for more sensitive study. The telescope will target black holes, supernova explosions, and will study the most extreme active galaxies. NuSTAR’s use of high-energy X-rays have an added bonus: it will be able to capture and compose the most detailed images ever taken in this end of the electromagnetic spectrum.

NuSTAR’s eyes are two Wolter-I optic units; once in orbit each will ‘look’ at the same patch of sky. The Wolter-I mirror works by reflecting an X-ray twice, once off of an upper mirror shaped like a parabola and again off a lower mirror shaped like a hyperbola. The mirrors are nearly parallel to the direction of the incoming X-ray, reflecting most of the X-ray instead of absorbing it, but the slight angle allows for a very small collection area per surface. To get a full picture, mirrors of varying size are nested together.

Each of NuSTAR’s eyes, each unit, are made of 133 concentric shells of mirrors shaped from flexible glass like that found in laptop computer screens. This is an improvement over past missions like Chandra and XMM-Newton that both used high density materials such as Platinum, Iridium and Gold as mirror coatings. These materials achieve great reflectivity for low energy X-rays but can’t capture high energy X-rays.

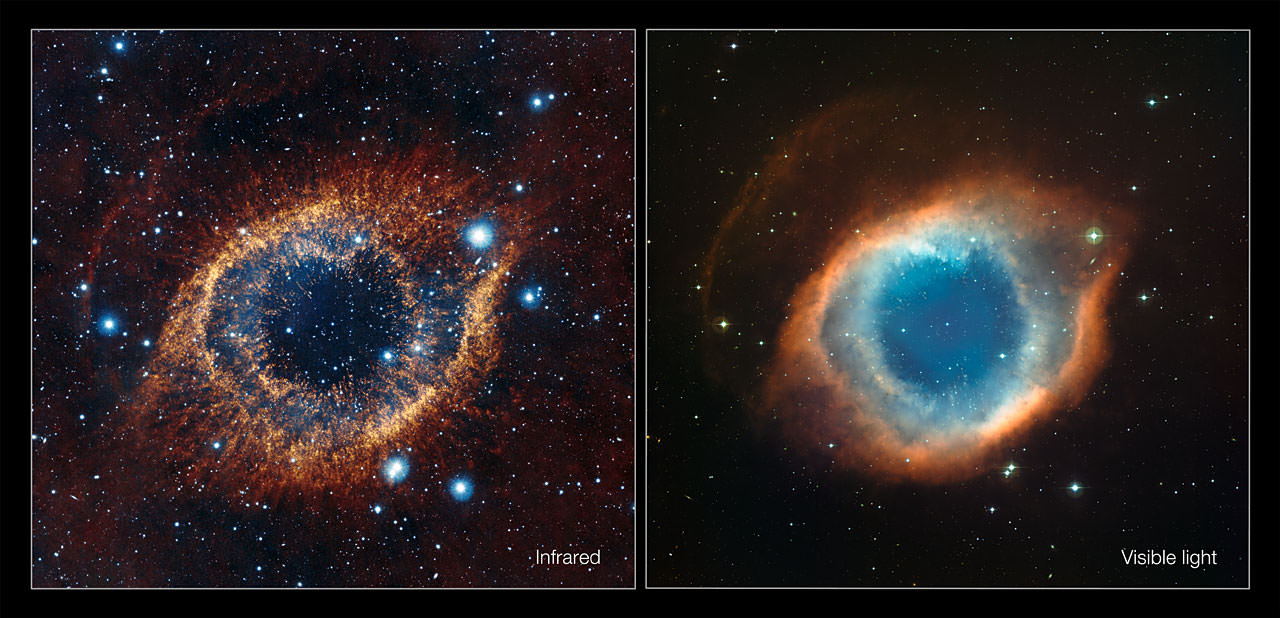

Like human eyes, NuSTAR’s optical units are co-aligned to give the telescope a wider field of view and enable the capture of more sensitive images. These images will be made into detailed composites by scientists on the ground.

Also like human eyes, NuSTAR’s optical units need to be distanced from one another since X-ray telescopes require long focal lengths. In other words, the optics must be separated by several meters from the detectors. NuSTAR does this with a 33 foot (10 metre) long mast or boom between units.

Previous X-ray missions have accommodated these long focal lengths by launching fully deployed observatories on large rockets. NuSTAR won’t. It has a unique deployable mast that will extend once the payload is in orbit. This allows for a launch on the small Pegasus rocket. Undeployed, the telescope measures just 2 metres in length and one metre in diameter.

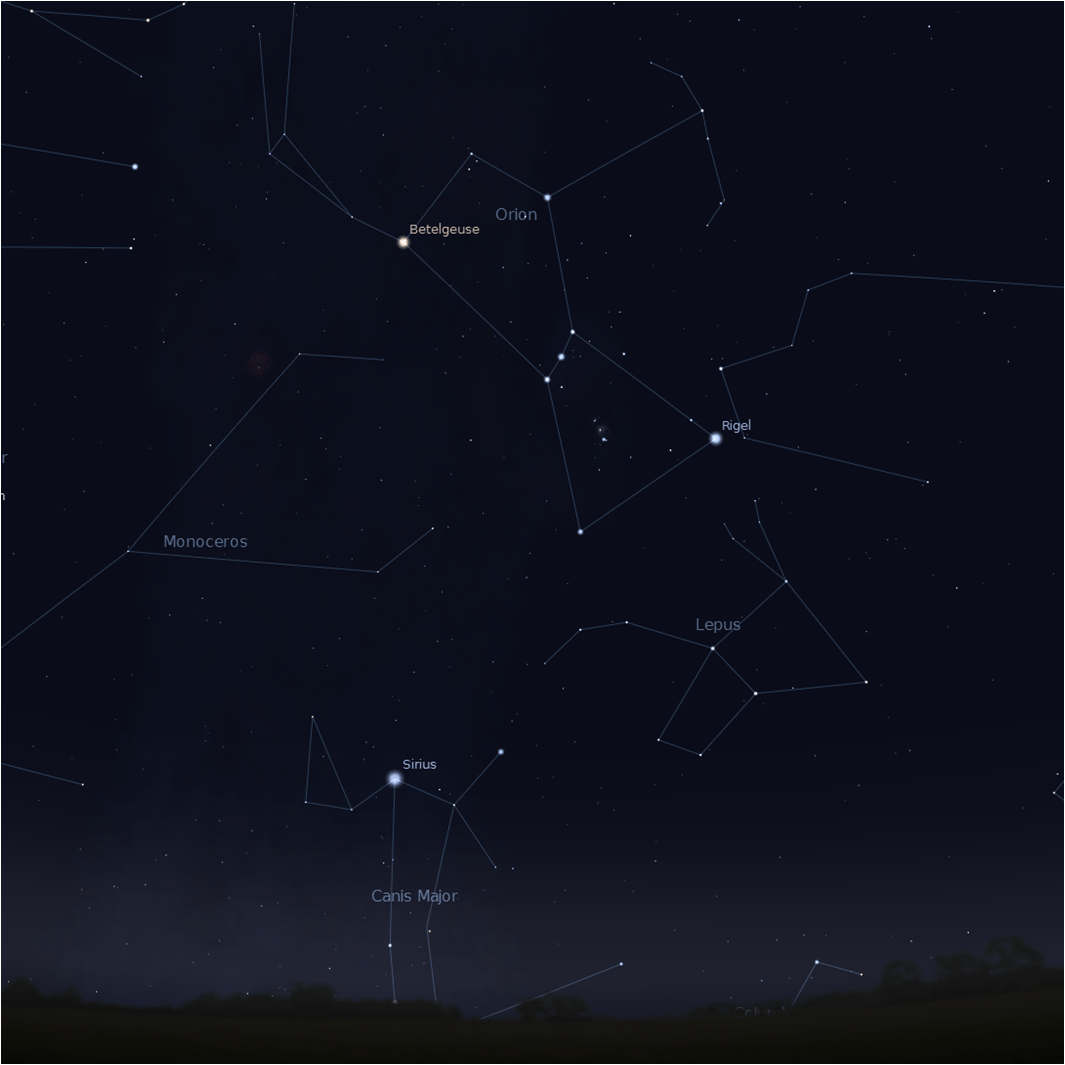

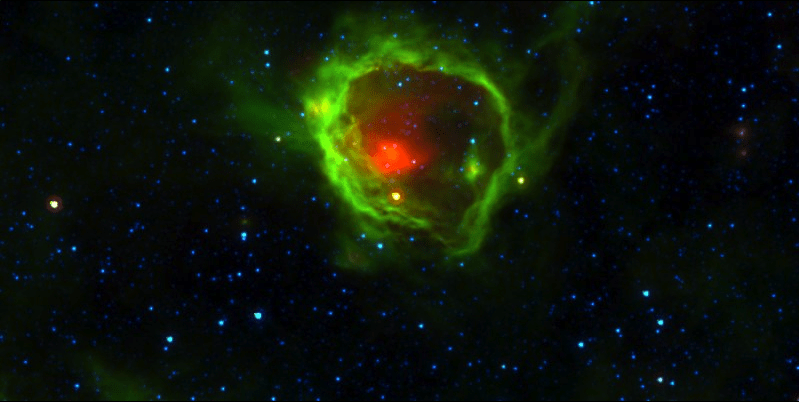

During its two-year primary mission, NuSTAR will map the celestial sky focussing on black holes, supernova remnants, and particle jets traveling near the speed of light. It will also look at the Sun. Observations of microflares could explain the temperature of the Sun’s corona. It will also search the Sun for evidence of a hypothesized dark matter particle to test a theory about dark matter.

“NuSTAR will provide an unprecedented capability to discover and study some of the most exotic objects in the universe, from the corpses of exploded stars in the Milky Way to supermassive black holes residing in the hearts of distant galaxies,” said Lou Kaluzienski, NuSTAR program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington.

The telescope shipped from the Orbital Sciences Corporation in Dulles, Virginia to Vandenberg Air Force Base in California on January 27. There, it will be mated to its Pegasus launch vehicle on February 17. It will launch from underneath the L-1011 “Stargazer” aircraft on March 14 after taking off near the equator from Kwajalein Atoll in the Pacific.

Source: NASA