[/caption]

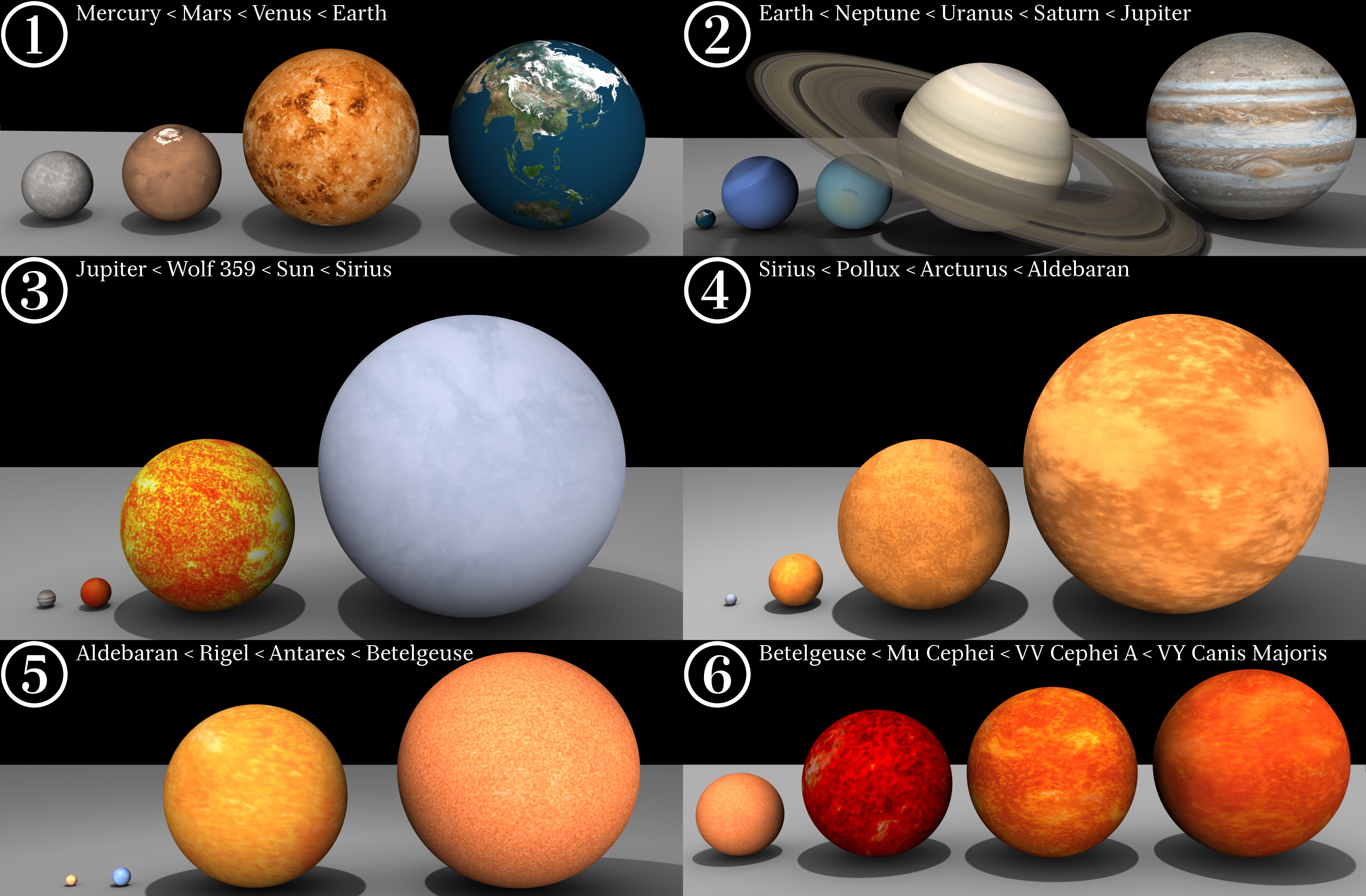

You may have seen one of these astronomical scale picture sequences, where you go from the Earth to Jupiter to the Sun, then the Sun to Sirius – and all the way up to the biggest star we know of VY Canis Majoris. However, most of the stars at the big end of the scale are at a late point in their stellar lifecycle – having evolved off the main sequence to become red supergiants.

The Sun will go red giant in 5 billion years or so – achieving a new radius of about one Astronomical Unit – equivalent to the average radius of the Earth’s orbit (and hence debate continues around whether or not the Earth will be consumed). In any case, the Sun will then roughly match the size of Arcturus, which although voluminously big, only has a mass of roughly 1.1 solar masses. So, comparing star sizes without considering the different stages of their stellar evolution might not be giving you the full picture.

Another way of considering the ‘bigness’ of stars is to consider their mass, in which case the most reliably confirmed extremely massive star is NGC 3603-A1a – at 116 solar masses, compared with VY Canis Majoris’ middling 30-40 solar masses.

The most massive star of all may be R136a1, which has an estimated mass of over 265 solar masses – although the exact figure is the subject of ongoing debate, since its mass can only be inferred indirectly. Even so, its mass is almost certainly over the ‘theoretical’ stellar mass limit of 150 solar masses. This theoretical limit is based on mathematically modelling the Eddington limit, the point at which a star’s luminosity is so high that its outwards radiation pressure exceeds its self-gravity. In other words, beyond the Eddington limit, a star will cease to accumulate more mass and will begin to blow off large amounts of its existing mass as stellar wind.

It’s speculated that very big O type stars might shed up to 50% of their mass in the early stages of their lifecycle. So for example, although R136a1 is speculated to have a currently observed mass of 265 solar masses, it may have had as much as 320 solar masses when it first began its life as a main sequence star.

So, it may be more correct to consider that the theoretical mass limit of 150 solar masses represents a point in a massive star’s evolution where a certain balancing of forces is achieved. But this is not to say that there couldn’t be stars more massive than 150 solar masses – it’s just that they will be always declining in mass towards 150 solar masses.

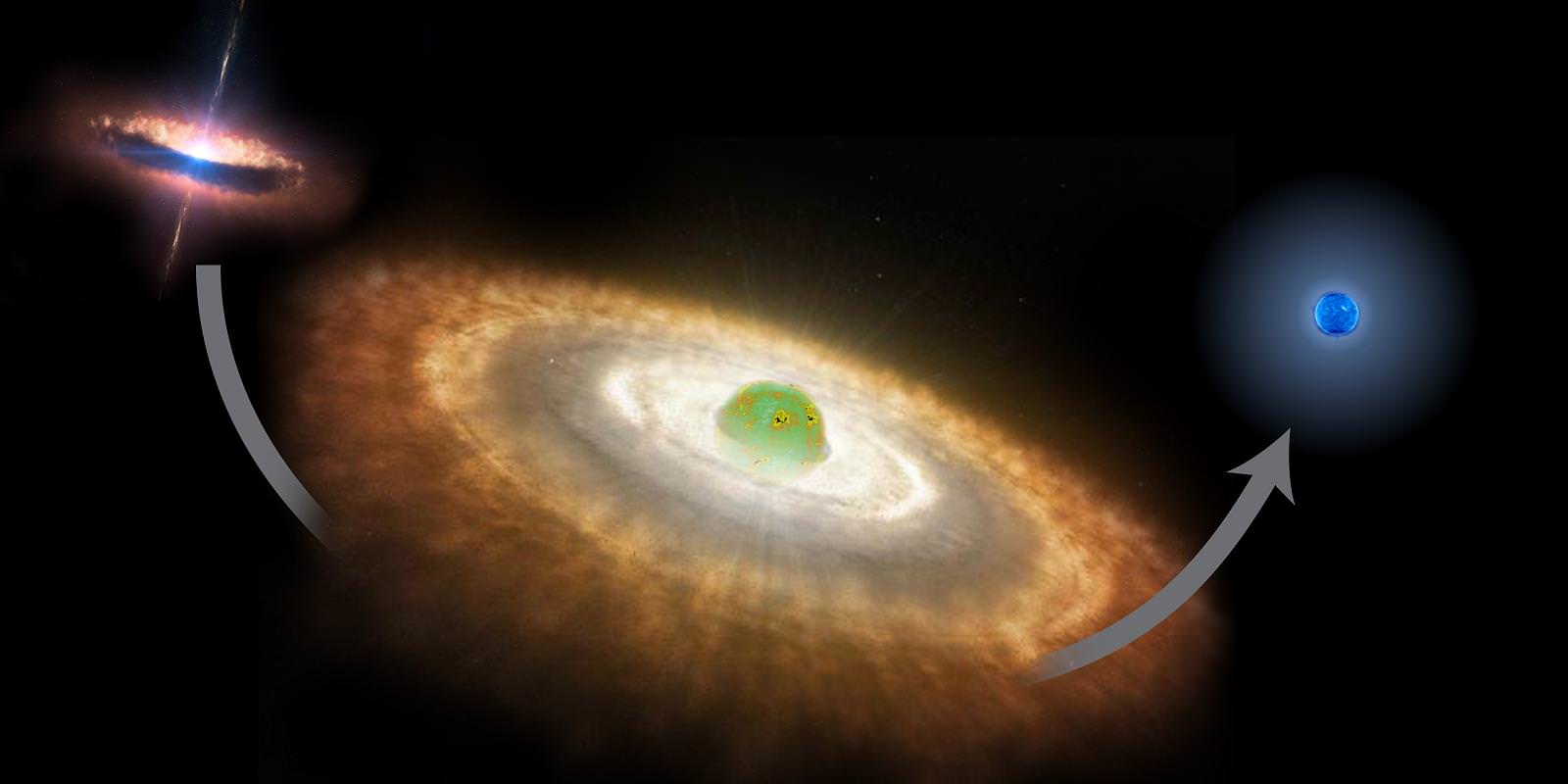

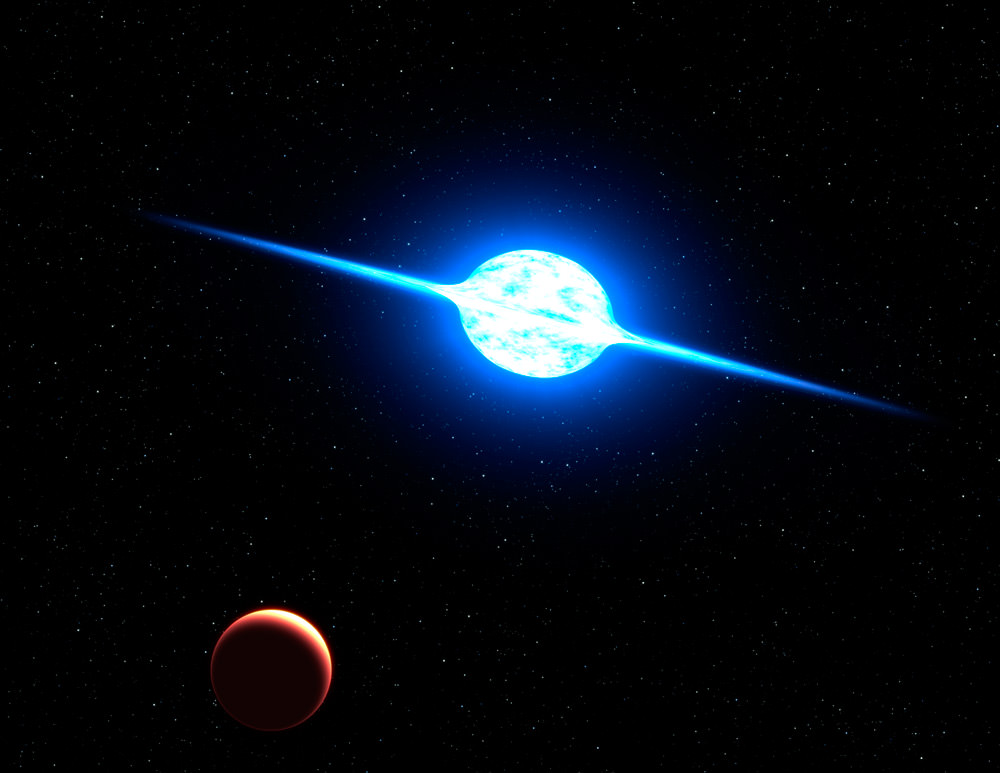

Having unloaded a substantial proportion of their initial mass such massive stars might continue as sub-Eddington blue giants if they still have hydrogen to burn, become red supergiants if they don’t – or become supernovae.

Vink et al model the processes in the early stages of very massive O type stars to demonstrate that there is a shift from optically thin stellar winds, to optically thick stellar winds at which point these massive stars can be classified as Wolf-Rayet stars. The optical thickness results from blown off gas accumulating around the star as a wind nebulae – a common feature of Wolf-Rayet stars.

Lower mass stars evolve to red supergiant stage through different physical processes – and since the expanded outer shell of a red giant does not immediately achieve escape velocity, it is still considered part of the star’s photosphere. There’s a point beyond which you shouldn’t expect bigger red supergiants, since more massive progenitor stars will follow a different evolutionary path.

Those more massive stars spend much of their lifecycle blowing off mass via more energetic processes and the really big ones become hypernovae or even pair-instability supernovae before they get anywhere near red supergiant phase.

So, once again it appears that maybe size isn’t everything.

Further reading: Vink et al Wind Models for Very Massive Stars in the Local Universe.