[/caption]

For some years now astronomers have been scratching their heads over the appearance of supernovae that detonate out in the middle of nowhere – rather than within a host galaxy.

Various hypotheses have been proposed, notably that they might be hypervelocity stars – which are stars flung out of their host galaxy due to an unfortunate coincidence of gravitational interactions. It’s thought that such interactions may accelerate those stars up to a velocity of more than 100 kilometers a second – that is, more than the escape velocity of your average galaxy.

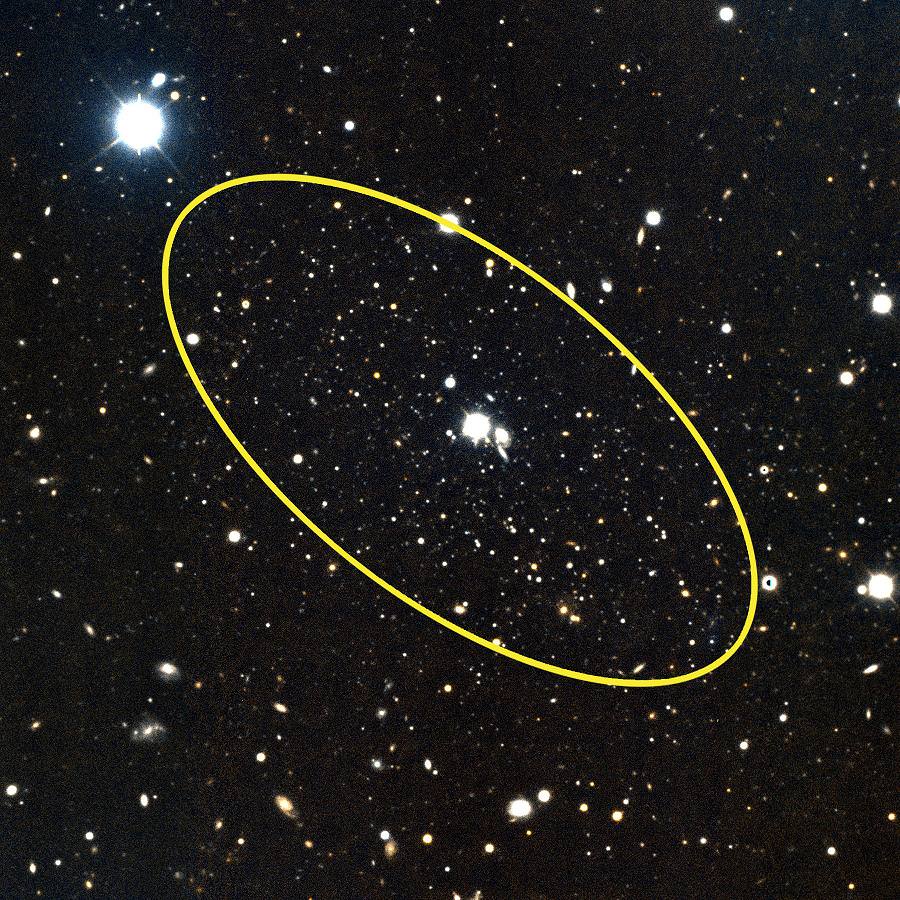

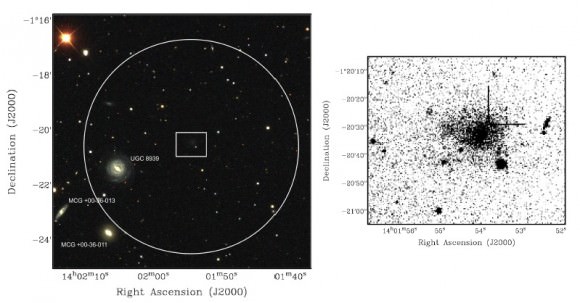

But Zinn et al suggest a more mundane suggestion for their particular orphan supernovae of interest, which is SN 2009z. They propose that it is in a galaxy, it’s just a galaxy that is very difficult to see.

They propose the supernova actually detonated within a low surface brightness galaxy, N271. From the images they have produced, this seems a reasonable claim – it’s just that low surface brightness galaxies (or LSBs) aren’t meant to have supernovae.

Since galaxies can appear as extended objects, rather than as point-like stars, we refer to them as having ‘surface brightness’ – which can vary across the object’s apparent surface. LSB’s are generally isolated field galaxies, rather than being grouped in amongst dense galaxy clusters. They are most often dwarf galaxies as well, but at least one spiral LSB has been identified.

The dimness of LSB galaxies is suggestive of them having almost no active star formation – either being too old, with no free hydrogen remaining for new star formation – or just not dense enough for much star formation to ever have taken off.

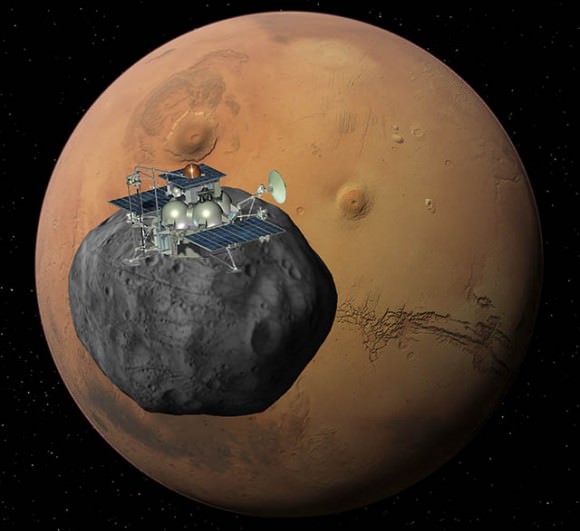

But here you have supernova SN 2009z that was most likely was contained within LSB galaxy N271. And SN 2009z was a Type II supernova – a massive and short-lived star that underwent core collapse. Indeed, it was a Type IIb with only a small shell of hydrogen when it detonated. Type IIb supernovae are probably massive stars which lose most, but not all, of their hydrogen shell through having it stripped off by a companion star in a binary system.

This all seems quite unusual behaviour for a galaxy that does not support active star formation. Zinn et al propose that LSB galaxies must go through short bursts of active star formation followed by long quiescent phases of almost no activity. This then suggests that the progenitor star of supernova SN 2009z was formed in the previous starburst period, before N271 quietened down again.

Of course, none of this need suggest that hypervelocity stars don’t exist – indeed several have been discovered since the first confirmed finding in 2005. All those known are associated with the Milky Way, since finding a single isolated hypervelocity star ejected by a distant galaxy is probably beyond the detection of our current technology – unless of course they go supernovae.

But given what we know so far:

• a hypervelocity star arises from a binary system’s unfortunate interaction with a galaxy’s central supermassive black hole;

• one binary member is captured, the other flung violently outwards at escape velocity.

• but, massive stars that go supernovae only have a main sequence life span of the order of millions of years;

• so, even at more than 100 kilometers a second, it’s unlikely that any are going to make it across the many light years distance from the center of a galaxy to its outer boundary before they detonate.

Putting all this together… orphan supernovae? Busted (well, unless we find one anyway).

Further reading: Zinn et al. Supernovae without host galaxies? The low surface brightness host of SN 2009Z.