[/caption]

Solar neutrino physics has quieted down over the past decade. In the past, it had been a source of major excitement and puzzlement for scientists as they struggled to detect these elusive particles emitted from the fusion reactions in the center of the Sun. Although difficult to detect, they provide the most direct probe of the Solar core. Once astronomers learned to detect them and solved the Solar neutrino problem, they were able to confirm their understanding of the main nuclear reaction that powers the sun, the proton-proton (pp) reaction. But now, astronomers have for the first time, detected the neutrinos of another, far rarer nuclear reaction, the proton-electron-proton (pep) reaction.

At any given time, several separate fusion processes are converting the Sun’s hydrogen into helium, creating energy as a byproduct. The main reaction requires the formation of deuterium (hydrogen with an extra neutron in the nucleus) as the first step in a series of events that leads to the creation of stable helium. This typically takes place by the fusion of two protons which ejects a positron, a neutrino, and a photon. However, nuclear physicists predicted an alternative method of creating the necessary deuterium. In it, a proton and electron fuse first, forming a neutron and a neutrino, and then they join with a second proton. Based on solar models, they predicted that only 0.23% of all Deuterium would be created by this process. Given the already elusive nature of neutrinos, the diminished production rate has made these pep neutrinos even more difficult to detect.

While they may be hard to detect, pep neutrinos are readily distinguishable from ones created by the pp reaction. The key difference is the energy they carry. Neutrinos from the pp reaction have a range of energy up to a maximum of 0.42 MeV, while pep neutrinos carry a very select 1.44 MeV.

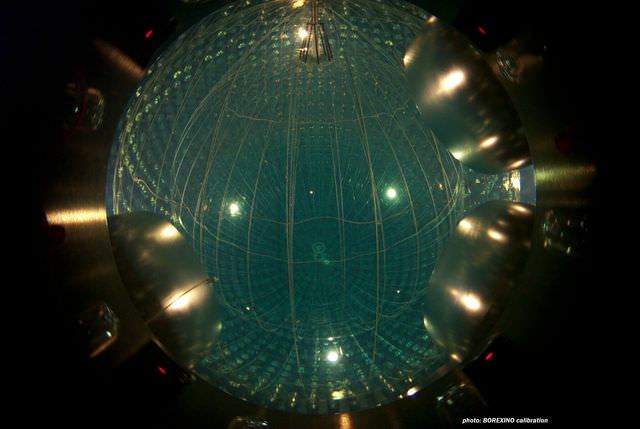

However, to pick out these neutrinos, the team had to carefully clean the data of signals from cosmic ray strikes which create muons that could then interact with carbon inside the detector to generate a neutrino with similar energy that might create a false positive. In addition, this process would also create a free neutron. To eliminate these, the team rejected all signals of neutrinos that occurred within a short amount of time from a detection of a free neutron. Overall, this indicated that the detector received 4,300 muons passing through it per day, which would generate 27 neutrons per 100tons of detector liquid, and similarly, 27 false positives.

Removing these detections, the team still found a signal of neutrinos with the appropriate energy and used this to estimate the total amount of pep neutrinos flowing through every square centimeter to be about 1.6 billion, per second, which they note is in agreement with predictions made by the standard model used to describe the interior workings of the Sun.

Aside from further confirming astronomers understanding of the processes that power the Sun, this finding also places constraints on another fusion process, the CNO Cycle. While this process is expected to be minor in the Sun (making only ~2% of all helium produced), it is expected to be more efficient in hotter, more massive stars and dominate in stars with 50% more mass than the Sun. Better understanding the limits of this process would help astronomers to clarify how those stars work as well.