[/caption]

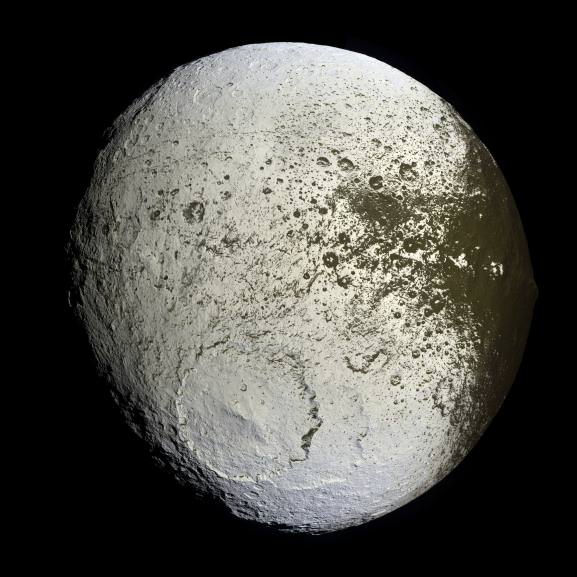

Although Saturn’s moon Iapetus was first discovered in 1671 by Giovanni Cassini, its behavior was extremely odd. Cassini was able to regularly find the moon when it was to the west of Saturn, but when he waited for it to swing around to Saturn’s east side, it seemed to vanish. It wasn’t until 1705 that Cassini finally observed Iapetus on the eastern side, but it took a better telescope because the side Iapetus presented when to the east was a full two magnitudes darker. Cassini surmised that this was due to a light hemisphere, presented when Iapetus was to the west, and a dark one, visible when it was to the east due to tidal locking.

With the advances in telescopes, the reason for this dark divide has been the subject of much research. The first explanations came in the 1970’s and a recent paper summarizes the work done so far on this fascinating satellite as well as expanding it to the larger context of some of Saturn’s other moons.

The foundation for the current model of Iapetus’ uneven display was first proposed by Steven Soter, one of the co-writers for Carl Sagans Cosmos series. During a colloquium of the International Astronomical Union, Soter proposed that micrometeorite bombardment of another of Saturn’s moons, Pheobe, drifted inwards and were picked up by Iapetus. Since Iapetus keeps one side facing Saturn at all times, this would similarly give it a leading edge that would preferentially pick up the dust particles. One of the great successes of this theory is that the center of the dark region, known as the Cassini Regio, is directly situated along the path of motion. Additionally, in 2009, astronomers discovered a new ring around Saturn, following Phoebe’s retrograde orbit, although slightly interior to the moon, adding to the suspicion that the dust particles should drift inwards, due to the Poynting-Robertson effect.

In 2010, a team of astronomers reviewing the images from the Cassini mission, noted that the coloration had properties that didn’t quite fit with Soter’s theory. If deposition from dust was the end of the story, it was expected that the transition between the dark region and the light would be very gradual as the angle at which they would strike the surface would become elongated, spreading out the incoming dust. However, the Cassini mission revealed the transitions were unexpectedly abrupt. Additionally, Iapetus’ poles were bright as well and if dust accumulation was as simple as Soter had suggested, they should be somewhat coated as well. Furthermore, spectral imaging of the Cassini Regio revealed that its spectrum was notably different than that of Phoebe. Another potential problem was that the dark surface extended past the leading side by more than ten degrees.

Revised explanations were readily forthcoming. The Cassini team suggested that the abrupt transition was due to a runaway heating effect. As the dark dust accumulated, it would absorb more light, converting it to heat and helped to sublimate more of the bright ice. In turn, this would reduce the overall brightness, again increasing the heating, and so on. Since this effect amplified the coloration, it could explain the more abrupt transition in much the same way as adjusting the contrast on an image will sharpen gradual transitions between colors. This explanation also predicted that the sublimated ice could travel around the far side of the moon, freezing out and enhancing the brightness on the other sides as well as the poles.

To explain the spectral differences, astronomers proposed that Phoebe may not be the only contributor. Within Saturn’s satellite system, there are over three dozen irregular satellites with dark surfaces which could also potentially contribute, altering the chemical makeup. But while this sounded like a tantalizingly straight-forward solution, confirmation would require further investigation. The new study, led by Daniel Tamayo at Cornell University, analyzed the efficiency with which various other moons could produce dust as well as the likelihood with which Iapetus could scoop it up. Interestingly, their results showed that Ymir, a mere 18 km in diameter, “should be roughly as important a contributor of dust to Iapetus as Phoebe”. Although none of the other moons, independently looked to be as strong of sources for dust, the sum of dust coming the remaining irregular, dark moons was found to be at least as important as either Ymir or Phoebe. As such, this explanation for the spectral deviation is well grounded.

The last difficulty, that of spreading dust past the leading face of the moon, is also explained in the new paper. The team proposes that eccentricities in the orbit of the dust allow it to strike the moon at odd angles, off from the leading hemisphere. Such eccentricities could be readily produced by solar radiation, even if the orbit of the originating body was not eccentric. The team carefully analyzed such effects and produced models capable of matching the dust distribution past the leading edge.

The combination of these revisions seem to secure Soter’s basic premise. A further test would be to see if other large satellites like Iapetus also showed signs of dust deposition, even if not so starkly divided since most other moons lack the synchronous orbit. Indeed, the moon Hyperion was found to have darker regions pooling in its craters when Cassini few by in 2007. These dark regions also revealed similar spectra to that of Cassini Regio. Saturn’s largest moon, Titan is also tidally locked and would be expected to sweep up particles on its leading edge, but due to its thick atmosphere, the dust would likely be spread moon-wide. Although difficult to confirm, some studies have suggested that such dust may help contribute to the haze Titan’s atmosphere exhibits.