[/caption]

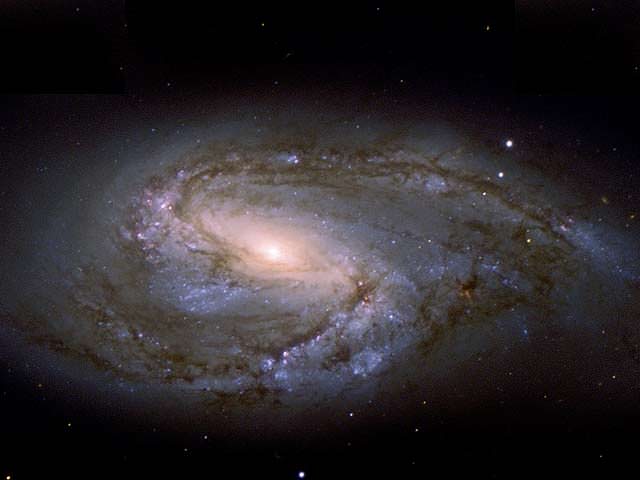

Spiral galaxies are one of the most captivating structures in astronomy, yet their nature is still not fully understood. Astronomers currently have two categories of theories that can explain this structure, depending on the environment of the galaxy, but a new study, accepted for publication in the Astrophysical Journal, suggests that one of these theories may be largely wrong.

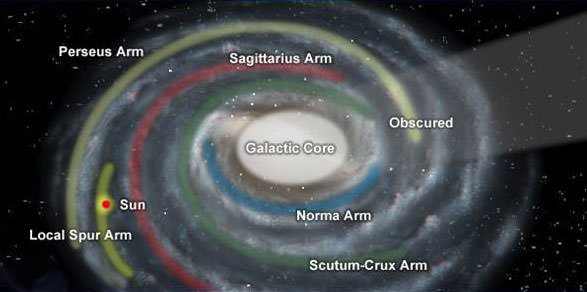

For galaxies with nearby companions, astronomers have suggested that tidal forces may draw out spiral structure. However, for isolated galaxies, another mechanism is required in which galaxies form these structures without intervention from a neighbor. A possible solution to this was first worked out in 1964 by Lin & Shu in which they suggested that the winding structure is merely an illusion. Instead, these arms weren’t moving structures, but areas of greater density which remained stationary as stars entered and exited them similar to how a traffic jam remains in position although the component cars travel in and out. This theory has been dubbed the Lin-Shu density wave theory and has been largely successful. Previous papers have reported a progression from cold, HI regions and dust on the inner portion of the spiral arms, that crash into this higher density region and trigger star formation, making hot O & B class stars that die before exiting the structure, leaving the lower mass stars to populate the remainder of the disk.

One of the main questions on this theory has been the longevity of the overdense region. According to Lin & Shu as well as many other astronomers, these structures are generally stable over long time periods. Others suggest that the density wave comes and goes in relatively short-lived, recurrent patterns. This would be similar to the turn signal on your car and the one in front of you at times seeming to synch up before getting out of phase again, only to line up again in a few minutes. In galaxies, the pattern would be composed of the individual orbits of the stars, which would periodically line up to create the spiral arms. Teasing out which of these was the case has been a challenge.

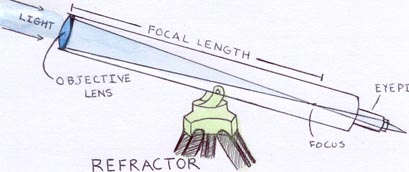

To do so, the new research, led by Kelly Foyle from McMaster University in Ontario, examined the progression of star formation as gas and dust entered the shock region produced by the Lin-Shu density wave. If the theory was correct, they should expect to find a progression in which they would first find cold HI gas and carbon monoxide, and then offsets of warm molecular hydrogen and 24 μm emission from stars forming in clouds, and finally, another offset of the UV emission of fully formed and unobscured stars.

The team examined 12 nearby spiral galaxies, including M 51, M 63, M 66, M 74, M 81, and M 95. These galaxies represented several variations of spiral galaxies such as grand design spirals, barred spirals, flocculent spirals and an interacting spiral.

When using a computer algorithm to examine each for offsets that would support the Lin-Shu theory, the team reported that they could not find a difference in location between the three different phases of star formation. This contradicts the previous studies (which were done “by eye” and thus subject to potential bias) and casts doubt on long lived spiral structure as predicted by the Lin-Shu theory. Instead, this finding is in agreement with the possibility of transient spiral arms that break apart and reform periodically.

Another option, one that salvages the density wave theory is that there are multiple “pattern speeds” producing more complex density waves and thus blurs the expected offsets. This possibility is supported by a 2009 study which mapped these speeds and found that several spiral galaxies are likely to exhibit such behavior. Lastly, the team notes that the technique itself may be flawed and underestimating the emission from each zone of star formation. To settle the question, astronomers will need to produce more refined models and explore the regions in greater detail and in more galaxies.