[/caption]

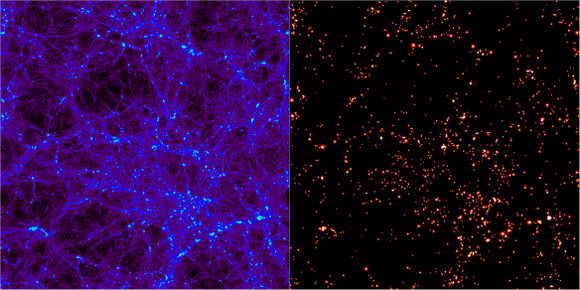

One of the successes of the ΛCDM model of the universe is the ability for models to create structures of with scales and distributions similar to those we view in the universe today. Or, at least that’s what astronomers tell us. While computer simulations can recreate numerical universes in a box, interpreting these mathematical approximations is a challenge in and of itself. To identify the components of the simulated space, astronomers have had to develop tools to search for structure. The results has been nearly 30 independent computer programs since 1974. Each promises to reveal the forming structure in the universe by finding regions in which dark matter halos form. To test these algorithms out, a conference was arranged in Madrid, Spain during the May of 2010 entitled “Haloes going MAD” in which 18 of these codes were put to the test to see how well they stacked up.

Numerical simulations for universes, like the famous Millennium Simulation begin with nothing more than “particles”. While these were undoubtedly small on a cosmological scale, such particles represent blobs of dark matter with millions or billions solar masses. As time is run forwards, they are allowed to interact with one another following rules that coincident with our best understanding of physics and the nature of such matter. This leads to an evolving universe from which astronomers must use the complicated codes to locate the conglomerations of dark matter inside which galaxies would form.

One of the main methods such programs use is to search for small overdensities and then grow a spherical shell around it until the density falls off to a negligible factor. Most will then prune the particles within the volume that are not gravitationally bound to make sure that the detection mechanism didn’t just seize on a brief, transient clustering that will fall apart in time. Other techniques involve searching other phase spaces for particles with similar velocities all nearby (a sign that they have become bound).

To compare how each of the algorithms fared, they were put through two tests. The first, involved a series of intentionally created dark matter halos with embedded sub-halos. Since the particle distribution was intentionally placed, the output from the programs should correctly find the center and size of the halos. The second test was a full fledged universe simulation. In this, the actual distribution wouldn’t be known, but the sheer size would allow different programs to be compared on the same data set to see how similarly they interpreted a common source.

In both tests, all the finders generally performed well. In the first test, there were some discrepancies based on how different programs defined the location of the halos. Some defined it as the peak in density, while others defined it as a center of mass. When searching for sub-halos, ones that used the phase space approach seemed to be able to more reliably detect smaller formations, yet did not always detect which particles in the clump were actually bound. For the full simulation, all algorithms agreed exceptionally well. Due to the nature of the simulation, small scales weren’t well represented so the understanding of how each detect these structures was limited.

The combination of these tests did not favor one particular algorithm or method over any other. It revealed that each generally functions well with regard to one another. The ability for so many independent codes, with independent methods means that the findings are extremely robust. The knowledge they pass on about how our understanding of the universe evolves allows astronomers to make fundamental comparisons to the observable universe in order to test the such models and theories.

The results of this test have been compiled into a paper that is slated for publication in an upcoming issue of the Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.