[/caption]

While planets orbiting twin stars are a staple of science fiction, another is having humans live on planets orbiting red giant stars. The majority of the story of Planet of the Apes takes place on a planet around Betelgeuse. Planets around Arcturus in Isaac Asimov’s Foundation series make up the capital of his Sirius Sector. Superman’s home planet was said to orbit a the fictional red giant, Rao. Races on these planets are often depicted as being old and wise since their stars are aged, and nearing the end of their lives. But is it really plausible to have such planets?

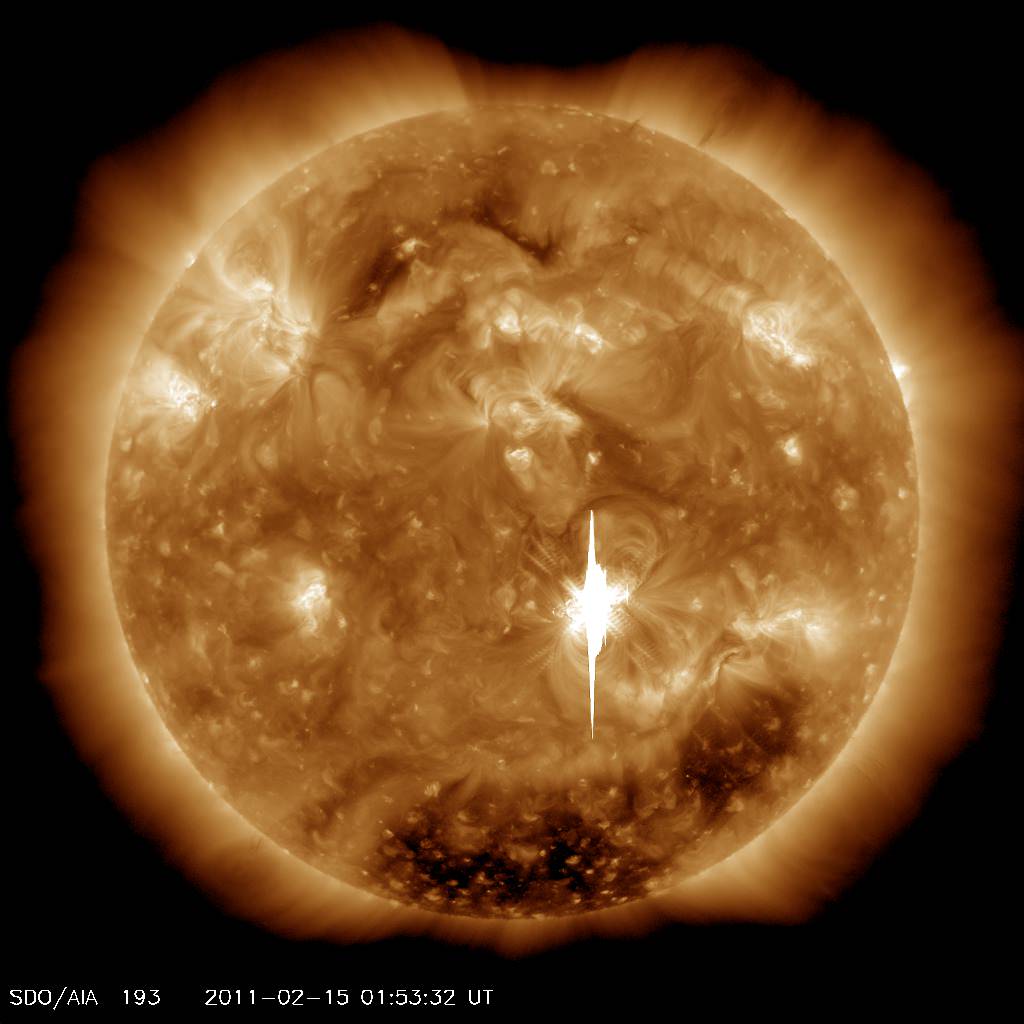

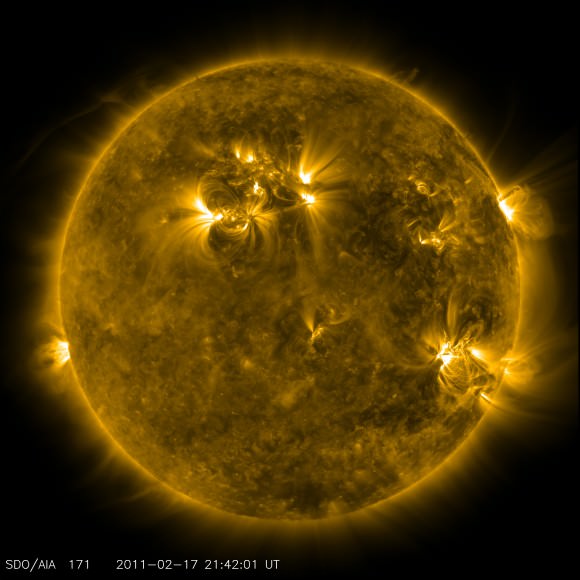

Stars don’t last forever. Our own Sun has an expiration date in about 5 billion years. At that time, the amount of hydrogen fuel in the core of the Sun will have run out. Currently, the fusion of that hydrogen into helium is giving rise to a pressure which keeps the star from collapsing in on itself due to gravity. But, when it runs out, that support mechanism will be gone and the Sun will start to shrink. This shrinking causes the star to heat up again, increasing the temperature until a shell of hydrogen around the now exhausted core becomes hot enough to take up the job of the core and begins fusing hydrogen to helium. This new energy source pushes the outer layers of the star back out causing it to swell to thousands of times its previous size. Meanwhile, the hotter temperature to ignite this form of fusion will mean that the star will give off 1,000 to 10,000 times as much light overall, but since this energy is spread out over such a large surface area, the star will appear red, hence the name.

So this is a red giant: A dying star that is swollen up and very bright.

Now to take a look at the other half of the equation, namely, what determines the habitability of a planet? Since these sci-fi stories inevitably have humans walking around on the surface, there’s some pretty strict criteria this will have to follow.

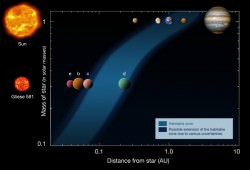

First off, the temperature must be not to hot and not to cold. In other words, the planet must be in the Habitable zone also known as the “Goldilocks zone”. This is generally a pretty good sized swath of celestial real estate. In our own solar system, it extends from roughly the orbit of Venus to the orbit of Mars. But what makes Mars and Venus inhospitable and Earth relatively cozy is our atmosphere. Unlike Mars, it’s thick enough to keep much of the heat we receive from the sun, but not too much of it like Venus.

The atmosphere is crucial in other ways too. Obviously it’s what the intrepid explorers are going to be breathing. If there’s too much CO2, it’s not only going to trap too much heat, but make it hard to breathe. Also, CO2 doesn’t block UV light from the Sun and cancer rates would go up. So we need an oxygen rich atmosphere, but not too oxygen rich or there won’t be enough greenhouse gasses to keep the planet warm.

The problem here is that oxygen rich atmospheres just don’t exist without some assistance. Oxygen is actually very reactive. It likes to form bonds, making it unavailable to be free in the atmosphere like we want. It forms things like H2O, CO2, oxides, etc… This is why Mars and Venus have virtually no free oxygen in their atmospheres. What little they do comes from UV light striking the atmosphere and causing the bonded forms to disassociate, temporarily freeing the oxygen.

Earth only has as much free oxygen as it does because of photosynthesis. This gives us another criteria that we’ll need to determine habitability: the ability to produce photosynthesis.

So let’s start putting this all together.

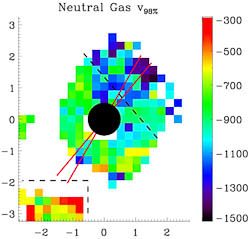

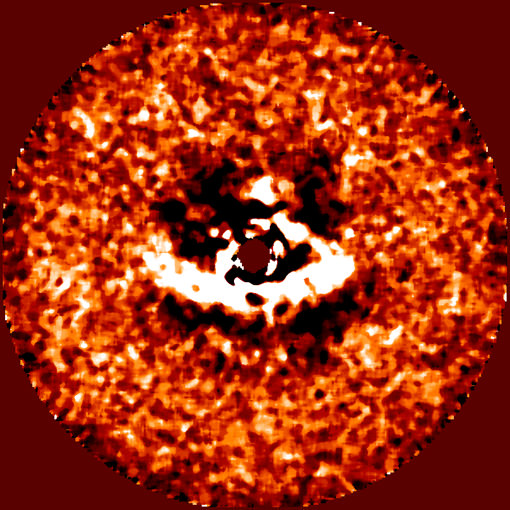

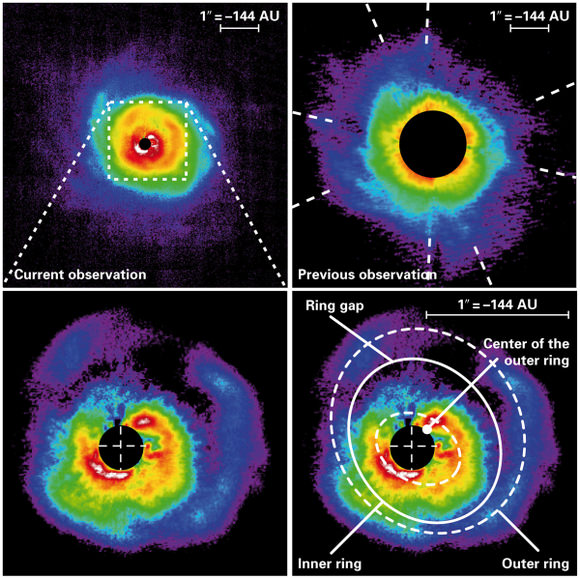

Firstly, the evolution of the star as it leaves the main sequence, swelling up as it becomes a red giant and getting brighter and hotter will mean that the “Goldilocks zone” will be sweeping outwards. Planets that were formerly habitable like the Earth will be roasted if they aren’t entirely swallowed by the Sun as it grows. Instead, the habitable zone will be further out, more where Jupiter is now.

However, even if a planet were in this new habitable zone, this doesn’t mean its habitable under the condition that it also have an oxygen rich atmosphere. For that, we need to convert the atmosphere from an oxygen starved one, to an oxygen rich one via photosynthesis.

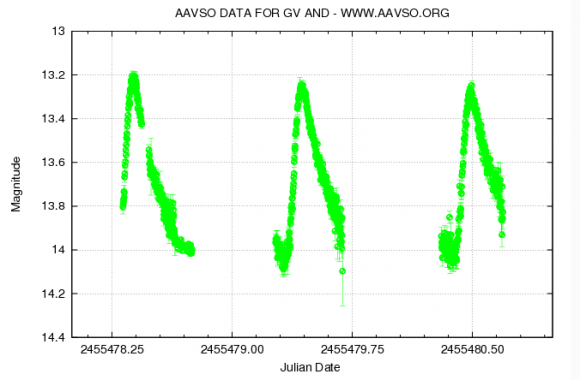

So the question is how quickly can this occur? Too slow and the habitable zone may have already swept by or the star may have run out of hydrogen in the shell and started contracting again only to ignite helium fusion in the core, once again freezing the planet.

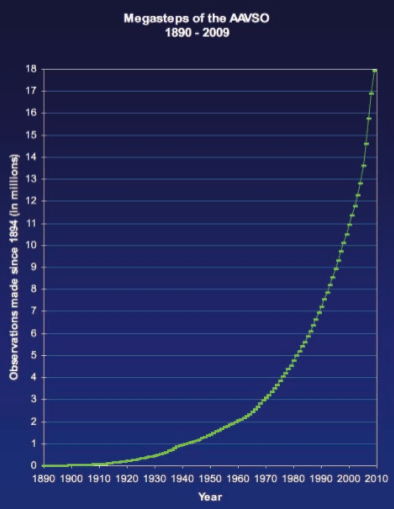

The only example we have so far is on our own planet. For the first three billion years of life, there was little free oxygen until photosynthetic organisms arose and started converting it to levels near that of today. However, this process took several hundred million years. While this could probably be increased by an order of magnitude to tens of millions of years with genetically engineered bacteria seeded on the planet, we still need to make sure the timescales will work out.

It turns out the timescales will be different for different masses of stars. More massive stars burn through their fuel faster and will thus be shorter. For stars like the Sun, the red giant phase can last about 1.5 billion years, so ~100x longer than is necessary to develop an oxygen rich atmosphere. For stars twice as massive as the Sun, that timescale drops to a mere 40 million years, approaching the lower limit of what we’ll need. More massive stars will evolve even more quickly. So for this to be plausible, we’ll need lower mass stars that evolve slower. A rough upper limit here would be a two solar mass star.

However, there’s one more effect we need to worry about: Can we have enough CO2 in the atmosphere to even have photosynthesis? While not nearly as reactive as oxygen, carbon dioxide is also subject to being removed from the atmosphere. This is due to effects like silicate weathering such as CO2 + CaSiO3 –> CaCO3 + SiO2. While these effects are slow they build up with geological timescales. This means we can’t have old planets since they would have had all their free CO2 locked away into the surface. This balance was explored in a paper published in 2009 and determined that, for an Earth mass planet, the free CO2 would be exhausted long before the parent star even reached the red giant phase!

So we’re required to have low mass stars that evolve slowly to have enough time to develop the right atmosphere, but if they evolve that slowly, then there’s not enough CO2 left to get the atmosphere anyway! We’re stuck with a real Catch 22. The only way to make this feasible again is to find a way to introduce sufficient amounts of new CO2 into the atmosphere just as the habitable zone starts sweeping by.

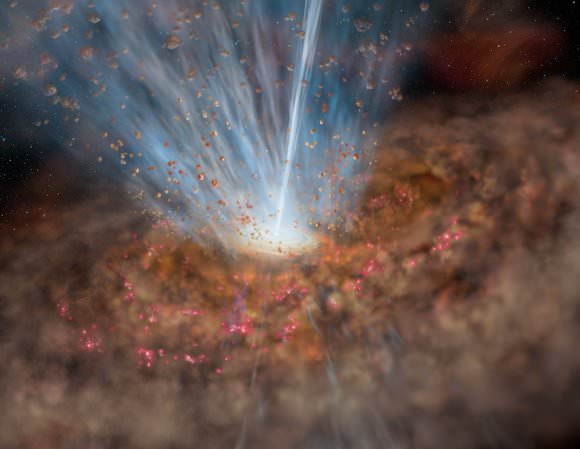

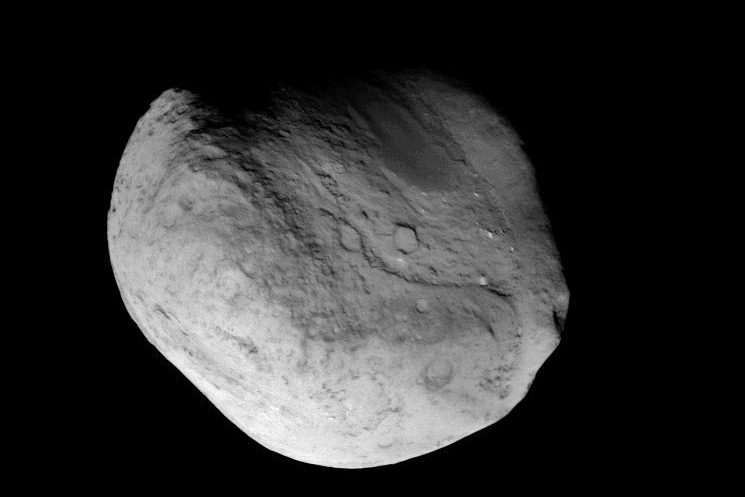

Fortunately, there are some pretty large repositories of CO2 just flying around! Comets are composed mostly of frozen carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide. Crashing a few of them into a planet would introduce sufficient CO2 to potentially get photosynthesis started (once the dust settled down). Do that a few hundred thousand years before the planet would enter the habitable zone, wait ten million years, and then the planet could potentially be habitable for as much as an additional billion years more.

Ultimately this scenario would be plausible, but not exactly a good personal investment since you’d be dead long before you’d be able to reap the benefits. A long term strategy for the survival of a space faring species perhaps, but not a quick fix to toss down colonies and outposts.