Greetings, fellow SkyWatchers! Are you ready for another great weekend of observing? If you’re thinking that it’s going to be boring because there’s Moon, then think again. If you were paying attention, you’d have noticed that Venus and Mars rose together this morning only about five degrees apart. Need more reasons to get out? Try 13 of them as you challenge yourself to see how many craterlets you can resolve in the mighty Clavius. Stars more to your liking? Then have a look at the Theta Virginis system or beautiful red Omega. Celebrate the Strawberry Moon, locate R Hydrae or just be on hand for an occultation event… It’s all part of the weekend scene! Grab your telescopes or binoculars and I’ll see you in the backyard.

Friday, June 5, 2009 – If you were up early this morning, did you see Venus and Mars no more than 30 minutes before dawn? The pair was very low – only about 20 degrees above the horizon -and about 5 degrees apart.

Now, let’s take a look at John Couch Adams, a discoverer of Neptune who was born on this date in 1819. Said he:

‘‘. . .the beginning of this week of investigating, as soon as possible after taking my degree, the irregularities in the motion of Uranus. . .in order to find out whether they may be attributed to the action of an undiscovered planet beyond it.’’

But that’s not all Adams contributed! He was the first to associate the Leonid meteor shower with the orbital path of a comet, and he also observed the Moon.

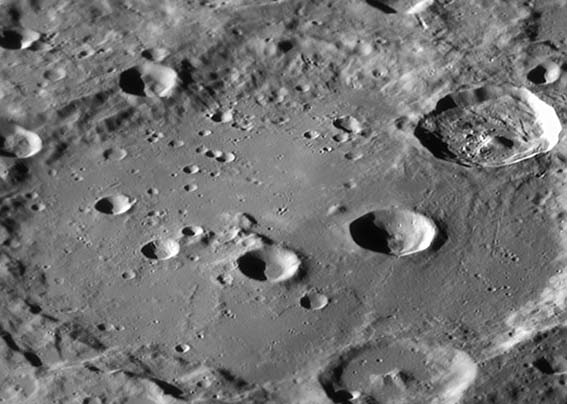

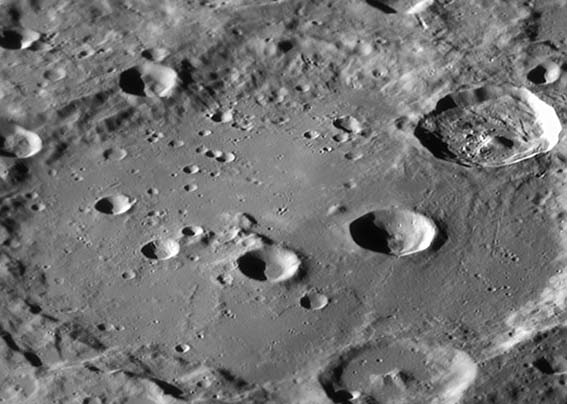

As we begin observing Selene this evening, let’s have a look at awesome crater Clavius. As a huge mountain-walled plain, Clavius will appear near the terminator tonight in the lunar Southern Hemisphere, rivaled only in sheer size by similarly structured Deslandres and Baily. Rising 1,646 meters above the surface, the interior wall slopes gently downward for a distance of almost 24 kilometers and spans 225 kilometers. Its crater-strewn walls are over 56 kilometers thick! Clavius is punctuated by many pockmarks and craters; the largest on the southeast wall is named Rutherford. Its twin, Porter, lies to the northeast. Long noted as a test of optics, Clavius crater can offer up to 13 such small craters on a steady night at high power. How many can you see?

If you want to continue tests of resolution, why not visit nearby Theta Virginis (RA 13 09 56 Dec -05 32 20)? It might be close to the Moon, but it’s 415 light-years away from Earth! The primary star is a white A-type subgiant, but it’s also a spectroscopic binary comprising two companions that orbit each other about every 14 years. In turn, this pair is orbited by a 9th magnitude F-type star that is a close 7.1’’ away from the primary. Look for the fourth member of the Theta Virginis system, well away at 70’’ but shining at a feeble magnitude 10.4.

If you want to continue tests of resolution, why not visit nearby Theta Virginis (RA 13 09 56 Dec -05 32 20)? It might be close to the Moon, but it’s 415 light-years away from Earth! The primary star is a white A-type subgiant, but it’s also a spectroscopic binary comprising two companions that orbit each other about every 14 years. In turn, this pair is orbited by a 9th magnitude F-type star that is a close 7.1’’ away from the primary. Look for the fourth member of the Theta Virginis system, well away at 70’’ but shining at a feeble magnitude 10.4.

Saturday, June 6, 2009 – Today is all about lunar history! We begin with the 1932 birth on this date of David Scott, the seventh person to walk on the Moon and the first to ride the Lunar Rover on the surface during the Apollo 15 mission. Sharing his birth date, but almost 500 years earlier, was the astronomer Regiomontanus (1436). Regiomontanus made observations of a comet, which were accurate enough to associate it with Comet Halley 210 years later, and his interest in the motion of the Moon led him to make the important observation that lunar distances could be used to determine longitude at sea! Let’s head to the Moon. . .

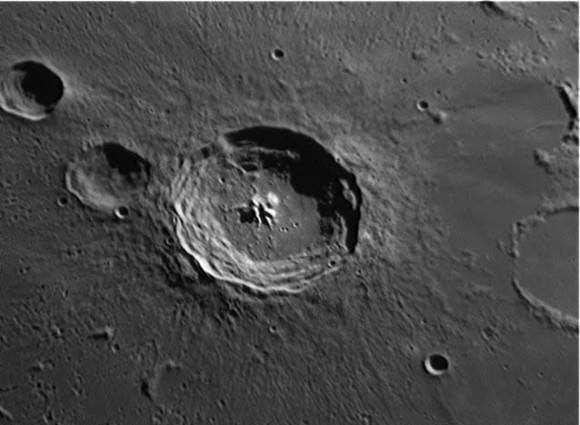

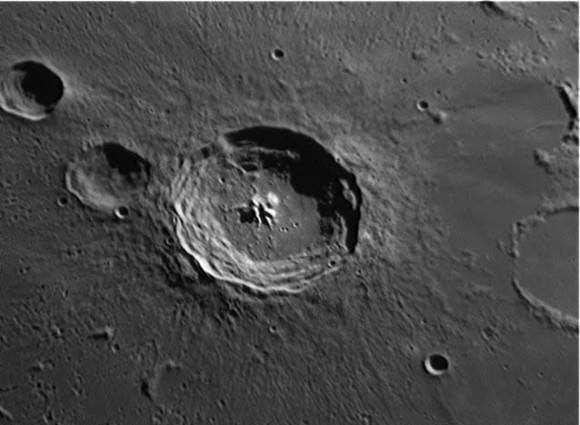

Although at first glance tonight crater Copernicus will try to steal the scene, head further south to capture another Lunar Club Challenge – Bullialdus. Even binoculars can make out this crater with ease near the center of Mare Nubium. If you’re scoping, power up – this one is fun! Very similar to Copernicus, note Bullialdus’ thick, terraced walls and central peak. If you examine the area around it carefully, you can note it is a much newer crater than shallow Lubiniezsky to its north and almost non-existent Kies to the south. On Bullialdus’ southern flank, it’s easy to make out itsA and B craters, as well as the interesting little Koenig to the southwest. Although it will be a bit overlit, if you head to the southeast shore of Mare Humorum, you can spot crater Regiomontanus as well. It’s just south of Purbach.

Now let’s starhop four finger-widths northwest of Beta Virginis for another unusual star – Omega (RA 11 38 27 Dec +08 08 03). Classed as an M-type red giant, this 480 light-year-distant beauty is also an irregular variable that fluxes by about half a magnitude. Although you won’t notice much change in this 5th magnitude star, it has a very pretty red coloration and is worth the time to view.

Now let’s starhop four finger-widths northwest of Beta Virginis for another unusual star – Omega (RA 11 38 27 Dec +08 08 03). Classed as an M-type red giant, this 480 light-year-distant beauty is also an irregular variable that fluxes by about half a magnitude. Although you won’t notice much change in this 5th magnitude star, it has a very pretty red coloration and is worth the time to view.

Sunday, June 7, 2009 – Today we celebrate the birth of Bernard Burke, co-discoverer of radio waves emitted from Jupiter. Listening to Jupiter’s radio signals is a wonderful hobby that can be practiced by anyone with enough room to set up a dipole antenna. If you’d like more information—or want to hear a recording of Jupiter yourself—visit Radio JOVE on the web! Tonight is Full Strawberry Moon, a name used by every Algonquin tribe in North America because the short season for harvesting the tasty red fruit comes each year during the month of June!

Sunday, June 7, 2009 – Today we celebrate the birth of Bernard Burke, co-discoverer of radio waves emitted from Jupiter. Listening to Jupiter’s radio signals is a wonderful hobby that can be practiced by anyone with enough room to set up a dipole antenna. If you’d like more information—or want to hear a recording of Jupiter yourself—visit Radio JOVE on the web! Tonight is Full Strawberry Moon, a name used by every Algonquin tribe in North America because the short season for harvesting the tasty red fruit comes each year during the month of June!

Tonight let’s have a look at a tasty red star – R Hydrae (RA 13 29 42 Dec -23 16 52) located a fist-width south of Spica. R Hydrae was the third long-term variable star discovered and was credited to Maraldi in 1704. Although Hevelius observed it 42 years earlier, it wasn’t recognized as variable because its changes happen over more than a year. At maximum, R reaches near 4th magnitude, but drops well below naked-eye perception to magnitude 10. During Maraldi’s and Hevelius’s time, this incredible star took over 500 days to cycle, but it has speeded up to around 390 days in the present century.

Tonight let’s have a look at a tasty red star – R Hydrae (RA 13 29 42 Dec -23 16 52) located a fist-width south of Spica. R Hydrae was the third long-term variable star discovered and was credited to Maraldi in 1704. Although Hevelius observed it 42 years earlier, it wasn’t recognized as variable because its changes happen over more than a year. At maximum, R reaches near 4th magnitude, but drops well below naked-eye perception to magnitude 10. During Maraldi’s and Hevelius’s time, this incredible star took over 500 days to cycle, but it has speeded up to around 390 days in the present century.

Why such a wide range? Scientists aren’t really sure. R Hydrae is a pulsing M-type giant whose evolution may be progressing more rapidly than expected due to changes in structure. What we do know is that it’s around 325 light-years away and approaching us at 10 kilometers per second! To the telescope, R will have a pronounced red coloration, which deepens near minimum. Nearby is 12th magnitude visual companion star Ho 381, which was first measured for angle position and distance in 1891. Since then, no changes in separation have been noted, leading us to believe the pair may be a true binary.

Now watch as the Moon devours a red star! Brilliant Antares will be less than a half degree away from the limb for most observers and will be occulted for some lucky others! Be sure to check the IOTA website for exact times and locations and enjoy!

Until next week? Ask for the Moon, but keep on reach for the stars!

This week’s awesome images are (in order of appearance): Clavius (credit—Wes Higgins), Theta Virginis (credit—Palomar Observatory, courtesy of Caltech), Bullialdus (credit—Wes Higgins), Omega Virginis (credit—Palomar Observatory, courtesy of Caltech), Nearside of the Moon as imaged by Apollo 11 (credit—NASA) and R Hydrae (credit—Palomar Observatory, courtesy of Caltech). We thank you so much!