Scientists studying the particles of comet dust brought to Earth by the Stardust spacecraft have uncovered a bit of a mystery. Research on the particles seem to indicate that while the comet formed in the icy fringes of the solar system, the dust appears to have been formed close to the sun and was bombarded by intense radiation before being flung out beyond Neptune and trapped in the comet. The finding opens the question of what was going on in the early life of the solar system to subject the dust to such intense radiation and hurl them hundreds of millions of miles from their birthplace.

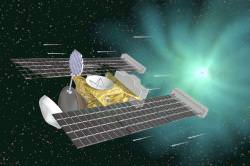

The Stardust spacecraft flew to Comet Wild-2 in 2004, coming approximately 150 miles from the comet’s nucleus, and captured particles of dust and gases from the comet’s coma and then returned those particles to Earth in 2006.

Researchers from the University of Minnesota and Nancy University in France analyzed gases locked in the tiny dust grains, which are about a quarter of a billionth of a gram in weight. They were looking for helium and neon, two noble gases that don’t combine chemically with other elements, and therefore would be in the same condition as when the comet dust formed.

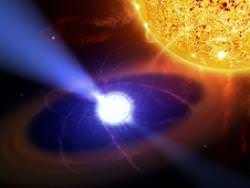

The analysis of the helium and neon isotopes suggests that some of the Stardust grains match a special type of carbonaceous material found in meteorites. The gases most likely came from a hot environment exposed to magnetic flares that must have been close to the young sun.

About 10 percent of the mass of Wild 2 is estimated to be from particles transported out from hot inner zones to the cold zone where Wild 2 formed. Earlier research showed that the comet formed in the Kuiper Belt, outside the orbit of Neptune, and only recently entered the inner regions of the solar system.

“Somehow these little high-temperature particles were transported out very early in the life of the solar system,” said Bob Pepin from the University of Minnesota. “The particles probably came from the first million years or even less, of the solar system’s existence.” That would be close to 4.6 billion years ago. If our middle-aged sun were 50 years old, then the particles were born in the first four days of its life.

The studies of cometary dust are part of a larger effort to trace the history of our celestial neighborhood.

“We want to establish what the solar system looked like in the very early stages,” said Pepin. “If we establish the starting conditions, we can tell what happened in between then and now.”

Stardust launched in February 1999, began collecting interstellar dust in 2000 and met up with Wild-2 in January 2004. It’s tennis raquet-sized collector made of an ultra-light material called aerogel, trapped aggregates of fine particles that hit at 13,000 miles per hour and split on impact. It is the first spacecraft to bring cometary dust particles back to Earth.

This study also has relevance in learning about the history of our own planet. “Because some scientists have proposed that comets have contributed these gases to the atmospheres of Earth, Venus and Mars, learning about them in comets would be fascinating,” Pepin said.

The research appears in the Jan. 4 issue of the journal Science

Original News Sources: University of Minnesota Press Release, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Press Release