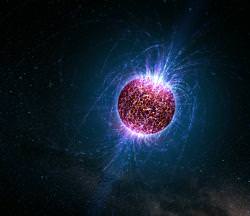

Some of the most extreme objects that we know of in the Universe are magnetars. These are small neutron stars with insanely powerful magnetic fields – they could erase your credit cards from millions of kilometres away. They occasionally have outbursts, blasting out radiation visible from across the galaxy. Now researchers think they have a better handle on where these outbursts are coming from. What’s causing them? That’s still a mystery.

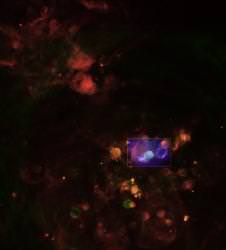

Back in 2003, astronomers watched as a previously unknown neutron star brightened by a factor of 100, briefly becoming visible to a collection of powerful observatories. After detecting pulsations of radiation coming from its surface, astronomers realized they were dealing with a magnetar.

Magnetars were once stars at least 8 times as massive as our own Sun. After the star exploded as a supernova, all that remained was the tiny – but massive – core. The entire mass of the Sun was packed into an object no larger than about 15 km (9 miles across).

Large mass packed into a small area makes it a neutron star, but a tremendously powerful magnetic field puts it into the magnetar class.

The analysis of this new magnetar, known as XTE J1810-197, allowed astronomers to trace the recent outburst to a region just below its surface. In fact, they were able to narrow down the region to an area about 3.5 km (2 miles) across. They could also determine that the magnetic field on the object is about 6 trillion times more powerful than the Earth’s magnetic field.

The process that actually created the outburst is still a mystery. Astronomers are certain that the magnetic field helped trigger the explosion, but they’re not sure what the mechanism is.

Original Source: ESA News Release