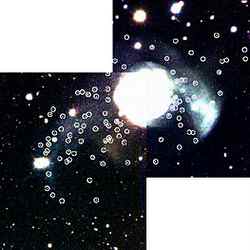

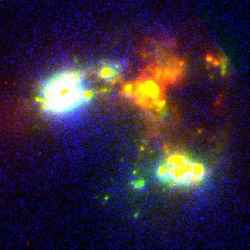

Haro 11 galaxy closeup view. Image credit: Hubble. Click to enlarge

A tiny galaxy has given astronomers a glimpse of a time when the first bright objects in the universe formed, ending the dark ages that followed the birth of the universe.

Astronomers from Sweden, Spain and the Johns Hopkins University used NASA’s Far Ultraviolet Spectroscopic Explorer (FUSE) satellite to make the first direct measurement of ionizing radiation leaking from a dwarf galaxy undergoing a burst of star formation. The result, which has ramifications for understanding how the early universe evolved, will help astronomers determine whether the first stars ? or some other type of object ? ended the cosmic dark age.

The team will present its results Jan. 12 at the American Astronomical Society’s 207th meeting in Washington, D.C.

Considered by many astronomers to be relics from an early stage of the universe, dwarf galaxies are small, very faint galaxies containing a large fraction of gas and relatively few stars. According to one model of galaxy formation, many of these smaller galaxies merged to build up today’s larger ones. If that is true, any dwarf galaxies observed now can be thought of as “fossils” that managed to survive ? without significant changes ? from an earlier period.

Led by Nils Bergvall of the Astronomical Observatory in Uppsala, Sweden, the team observed a small galaxy, known as Haro 11, which is located about 281 million light years away in the southern constellation of Sculptor. The team’s analysis of FUSE data produced an important result: between 4 percent and 10 percent of the ionizing radiation produced by the hot stars in Haro 11 is able to escape into intergalactic space.

Ionization is the process by which atoms and molecules are stripped of electrons and converted to positively charged ions. The history of the ionization level is important to understanding the evolution of structures in the early universe, because it determines how easily stars and galaxies can form, according to B-G Andersson, a research scientist in the Henry A. Rowland Department of Physics and Astronomy at Johns Hopkins, and a member of the FUSE team.

“The more ionized a gas becomes, the less efficiently it can cool. The cooling rate in turn controls the ability of the gas to form denser structures, such as stars and galaxies,” Andersson said. The hotter the gas, the less likely it is for structures to form, he said.

The ionization history of the universe therefore reveals when the first luminous objects formed, and when the first stars began to shine.

The Big Bang occurred about 13.7 billion years ago. At that time, the infant universe was too hot for light to shine. Matter was completely ionized: atoms were broken up into electrons and atomic nuclei, which scatter light like fog. As it expanded and then cooled, matter combined into neutral atoms of some of the lightest elements. The imprint of this transition today is seen as cosmic microwave background radiation.

The present universe is, however, predominantly ionized; astronomers generally agree that this reionization occurred between 12.5 and 13 billion years ago, when the first large-scale galaxies and galaxy clusters were forming. The details of this ionization are still unclear, but are of intense interest to astronomers studying these so-called “dark ages” of the universe.

Astronomers are unsure if the first stars or some other type of object ended those dark ages, but FUSE observations of “Haro 11” provide a clue.

The observations also help increase understanding of how the universe became reionized. According to the team, likely contributors include the intense radiation generated as matter fell into black holes that formed what we now see as quasars and the leakage of radiation from regions of early star formation. But until now, direct evidence for the viability of the latter mechanism has not been available.

“This is the latest example where the FUSE observation of a relatively nearby object holds important ramifications for cosmological questions,” said Dr. George Sonneborn, NASA/FUSE Project Scientist at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

This result has been accepted for publication by the European journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Original Source: JHU News Release