Image credit: NASA

New research indicates that electrons may surf on magnetic waves driven by the solar wind, and get accelerated to the point they can cause some serious damage to spacecraft orbiting the Earth. The process is a result of the interaction between the Earth’s magnetic field and fluctuations in the density of the solar wind. As the density of the solar wind changes, it causes waves in the magnetic field to ripple back to the Earth. Electrons can be caught in these ripples and surf back to the Earth so fast they can damage delicate electronics in space.

“Killer” electrons capable of wreaking havoc on orbiting spacecraft may “surf” magnetic waves driven by the solar wind, according to a team of space scientists.

The team from Boston University and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) combined observations from NASA and NOAA spacecraft to identify a phenomenon that explains how the solar wind makes waves in Earth’s magnetic field (magnetosphere). Ordinary electrons orbiting the Earth in the Van Allen radiation belts may boogyboard the waves, accelerating to near the speed of light, with energies 300-500 times greater than the electrons in a television screen.

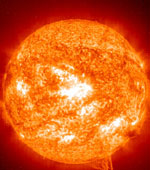

The solar wind is a stream of electrically charged particles blown constantly from the Sun. The magnetosphere is a cavity formed when the solar wind encounters the Earth’s magnetic field. When the solar wind density is high and comes up against the magnetosphere, the magnetosphere gets compressed. When the wind density is low, the magnetosphere expands. The researchers discovered that the solar wind contains periodic structures of high and low density, driving a periodic “breathing” action of the magnetosphere and the global generation of magnetic waves.

It’s known that if the frequency of these waves matches the frequency of the electrons in their motion in the Van Allen belt, the electrons can be accelerated, significantly boosting their energies. The process is similar to a boogyboarder catching a wave. Some electrons “ride the wave” and gain so much energy that they can then damage expensive spacecraft.

“If we can confirm this as a significant mechanism for making the waves that accelerate ‘killer’ electrons, then scientists using data from satellites like Wind could develop advance warning for spacecraft operators that their spacecraft may be in danger of excessive and damaging radiation exposure,” said Dr. Barbara Giles, project scientist for the Polar spacecraft at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, Greenbelt, Md.

When electrons become this energetic, they can penetrate to the interior of spacecraft. Once inside electronic parts, they build up static electricity that can short circuit a critical part or put the spacecraft into a bad operating mode.

“What’s new and exciting about this research is that people had always looked for mechanisms internal to the magnetosphere for generating these waves,” said Dr. Larry Kepko, research associate at Boston University and lead author of two papers on this research, one published in the Journal of Geophysical Research in June 2003 and the other in Geophysical Research Letters in 2002. “But here we’ve found an external mechanism – the solar wind itself.”

NASA’s Polar and Wind satellites, along with NOAA’s Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite (GOES), provided the key observations leading the team to this conclusion. Polar confirmed that the waves are not local, but global. The Wind satellite was the primary source for identifying the density structures in the solar wind that drive the magnetosphere. GOES provided data about the Earth’s magnetosphere as it increased and decreased in size.

“We already knew that the solar wind has density structures and that magnetic waves can accelerate electrons,” said Dr. Harlan Spence, associate professor of astronomy at Boston University and co-author of the two papers on this research. “What we didn’t know was that the solar wind structures can be periodic and drive magnetic waves. These new observations may provide a missing link between the two.”

The ultimate source of these newly discovered solar wind structures is still a mystery, but the team speculates that the Sun may play a direct role. “The solar wind density variations are partly controlled by the pattern of magnetic reconnection, the twisting and snapping of magnetic field lines, on the surface of the Sun,” says Dr. Kepko. “Reconnection occurring in a systematic, periodic manner may produce the observed periodic density structures in the solar wind. There is some evidence that this may be occurring, but further research is required to establish a definitive link.”

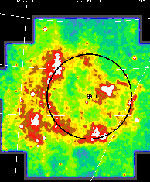

The Van Allen radiation belts were discovered in 1958 by Dr. James Van Allen and his team at the University of Iowa with Explorers 1 and 3, the first satellites successfully launched by the United States. They are belts of electrically charged particles trapped by the Earth’s magnetic field. Since the particles are electrically charged (mostly protons and electrons), they feel magnetic forces and are constrained to spiral around invisible lines of magnetic force that comprise the Earth’s magnetic field. There are actually two donut-shaped belts in the Van Allen system, one inside the other with the Earth in the “hole” of the inner belt. The inner belt, made up of high-speed protons, is located at altitudes between 430 and 7,500 miles (about 700 to 12,000 km) above the Earth. The outer belt is made of high-speed electrons and appears at altitudes between 15,500 and 25,000 miles (about 25,000 to 40,000 km) above Earth. Spacecraft operators try to avoid orbits in these regions, but sometimes these altitudes are best for a particular mission, or the spacecraft must pass through the belts during part of its orbit or to escape the Earth entirely.

NASA’s Polar and Wind satellites, together known as the “Global Geospace Science Program,” are dedicated to helping scientists understand how particles and energy from the Sun flow through, and interact with, the Earth’s space environment.

NOAA is dedicated to gathering data about the oceans, the atmosphere, space, and the Sun. Its GOES satellite system is the basic element for U.S. weather monitoring and forecasting. Dr. Howard Singer from NOAA is a third co-author on the 2002 paper about this research.

Original Source: NASA News Release