Have you seen the amazing pics? A bright comet graces evening skies this month, assuring that 2015 is already on track to be a great year for astronomy.

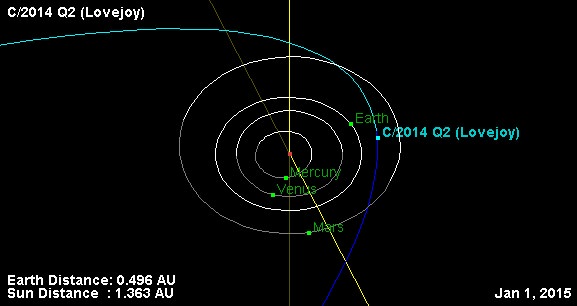

We’re talking about Comet C/2014 Q2 Lovejoy. Discovered by comet hunter extraordinaire Terry Lovejoy on August 17th, 2014, this denizen of the Oort Cloud has already wowed observers as it approaches its passage perihelion through the inner solar system in the coming week.

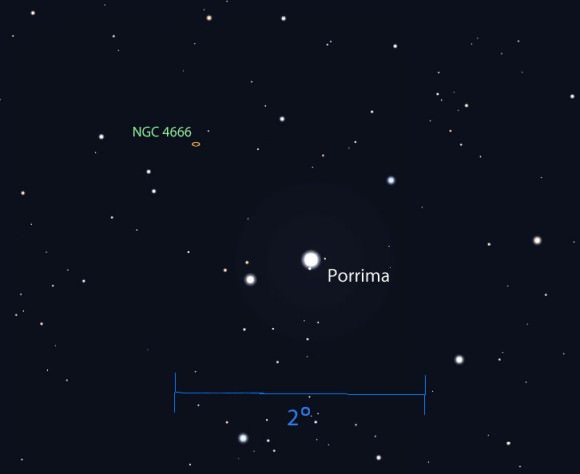

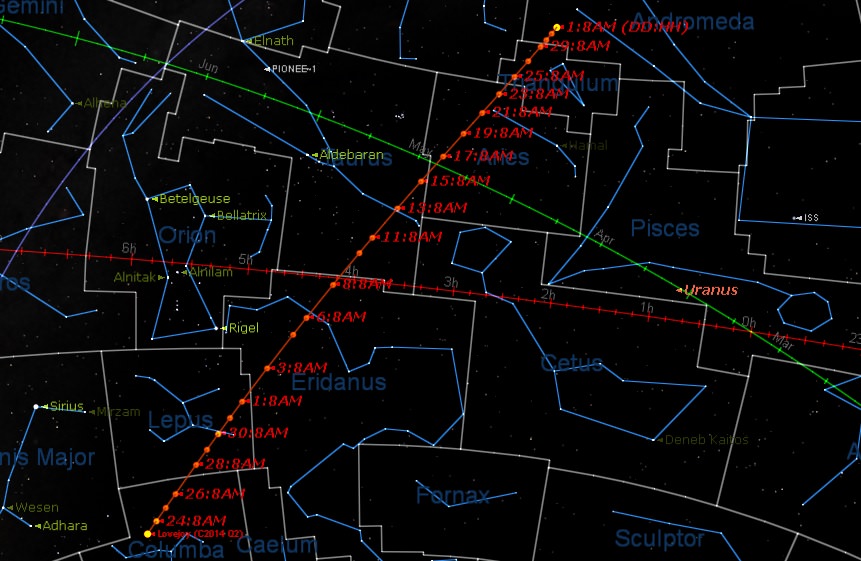

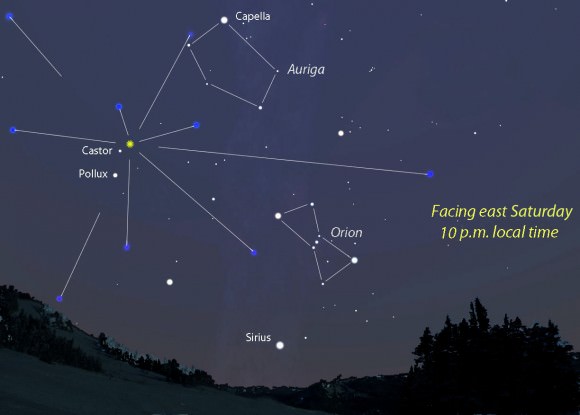

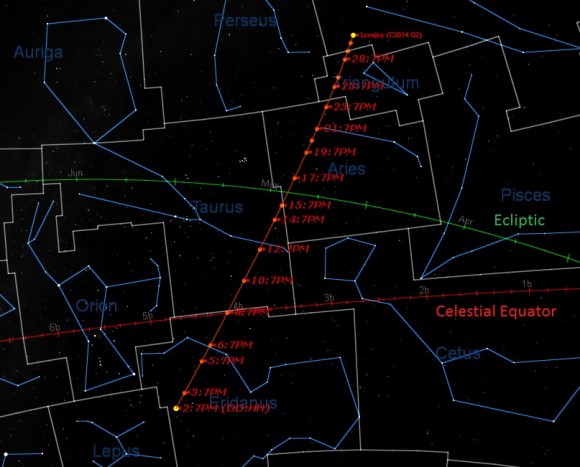

First, our story thus far. We’ve been following all Comet Q2 Lovejoy action pretty closely here at Universe Today, from its surreptitious brightening ahead of schedule, to its recent tail disconnection event, to its photogenic passage past the +8.6 magnitude globular cluster Messier 79 (M79) in the constellation Lepus. We also continue to be routinely blown away by reader photos of the comet. And, like the Hare for which Lepus is named, Q2 Lovejoy is now racing rapidly northward, passing into the rambling constellation of Eridanus the River before entering the realm of Taurus the Bull on January 9th and later crossing the ecliptic plane in Aries.

And the best window of opportunity for spying the comet is coming right up. We recently caught our first sight of Q2 Lovejoy a few evenings ago with our trusty Canon 15x 45 image-stabilized binocs from Mapleton, Maine. Even as seen from latitude 47 degrees north and a frosty -23 Celsius (-10 Fahrenheit) — a far cry from our usual Florida based perspective — the comet was an easy catch as a bright fuzz ball. Q2 Lovejoy was just outside of naked eye visibility for us this week, though I suspect that this will change as the Moon moves out of the evening picture this weekend.

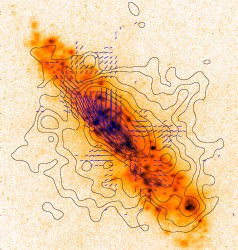

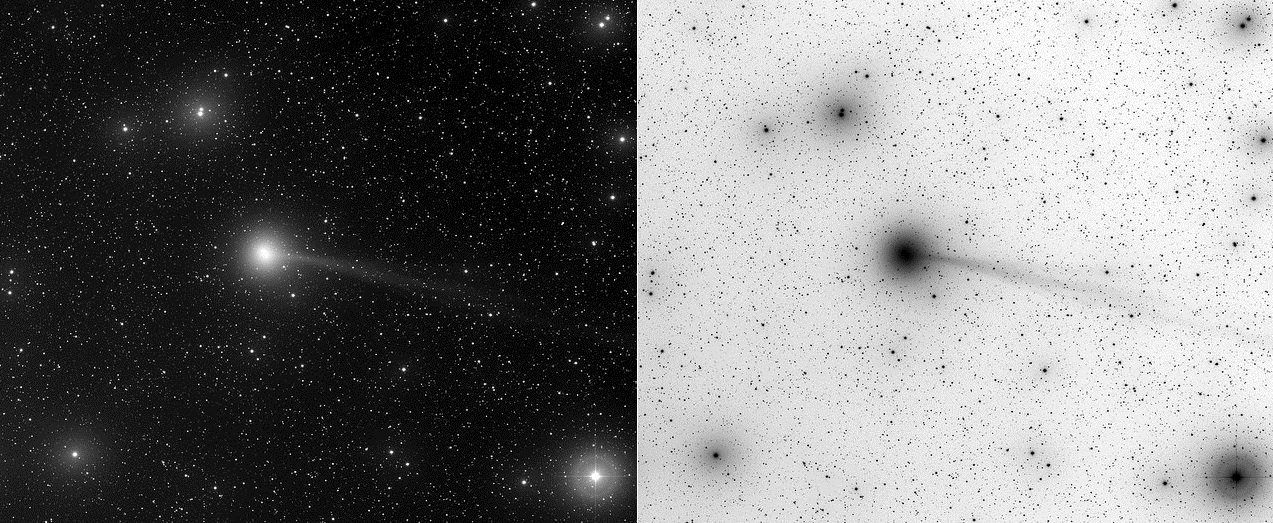

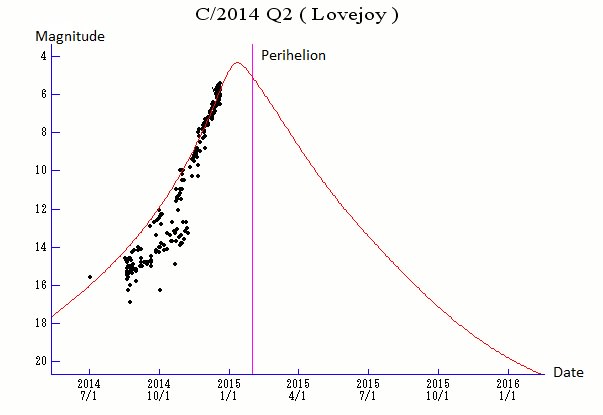

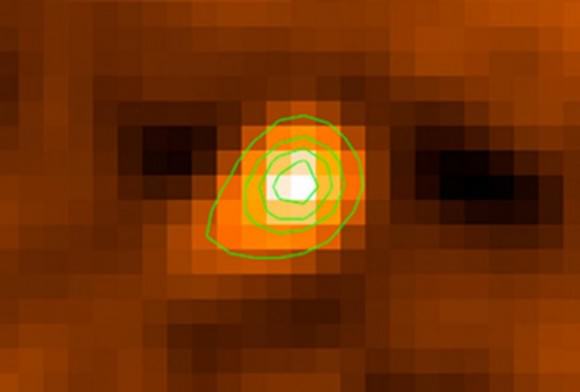

Currently shining at magnitude +5.5, Comet Q2 Lovejoy has already been spied by eagle-eyed observers unaided from dark sky sites to the south. Astrophotographers have revealed its long majestic dust and ion tails, as well as the greenish hue characteristic of bright comets. That green color isn’t kryptonite, but the fluorescing of diatomic carbon and cyanogen gas shed by the comet as it’s struck by ultraviolet sunlight. This greenish color is far more apparent in photographs, though it might just be glimpsed visually if the intrinsic brightness of the coma exceeds expectations. Q2 Lovejoy just passed opposition at 0.48 AU from the Earth today on January 2nd, and will make its closest passage from our fair world on January 7th at 0.47 AU (43.6 million kilometres) distant.

What’s so special about the coming week? Well, we also cross a key milestone for evening observing, as the light-polluting Moon reaches Full phase on Sunday January 5th at 4:54 UT (11:54 PM EDT on the 4th) and begins sliding out of the evening sky on successive evenings. That’s good news, as Comet Q2 Lovejoy enters the “prime time” evening sky and culminates over the southern horizon at around 10:30 PM local this weekend, then 8:00 PM on January the 15th, and just before 6:00 PM by January 31st.

While many comets put on difficult to observe dusk or dawn appearances — the 2013 apparition of another comet, C/2011 L4 PanSTARRS comes to mind — Q2 Lovejoy is well placed this month in the early evening hours.

The current projected peak brightness for Comet Q2 Lovejoy is +4th magnitude right around mid-January. Already, the comet is bright enough and well-placed to the south for northern hemisphere observers that it’s possible to catch astrophotos of the comet along with foreground objects. If you’ve got a tripod mounted DSLR give it a try… it’s as simple as aiming, focusing manually with a wide field of view, and taking 10 to 30 second exposures to see what turns up. Longer shots will call for sky tracking via a barn-door or motorized mount. Binoculars are you friend in your comet-hunting quest, as they can be readily deployed in sub-zero January temps and provide a generous field of view.

Q2 Lovejoy will also pass near the open clusters of the Hyades and the Pleiades through mid-January, and cross into the constellations of Aries and Triangulum by late January before heading northward to pass between the famous Double Cluster in Perseus and the Andromeda Galaxy M31 in February, proving further photo ops.

From there, Q2 Lovejoy is expected to drop below naked eye visibility in late February before passing very near the North Star Polaris and the northern celestial pole at the end of May on its way out of the inner solar system on its 8,000 year journey.

So, although 2014 didn’t produce the touted “comet of the century,” 2015 is already getting off to a pretty good start in terms of comets. We’re out looking nearly every clear night, and the next “big one” could always drop by at anytime… but hopefully, the first discovery baring the name “Comet Dickinson” will merely put on a spectacular show, and not prove to be an extinction level event…

– Got images of Comet Q2 Lovejoy? Send ‘em in to Universe Today.

– Up late looking for comets? Be sure to also check out the Quadrantid meteors this weekend.

-What other comets offer good prospects in 2015? Check out our Top 101 Events for the Year.