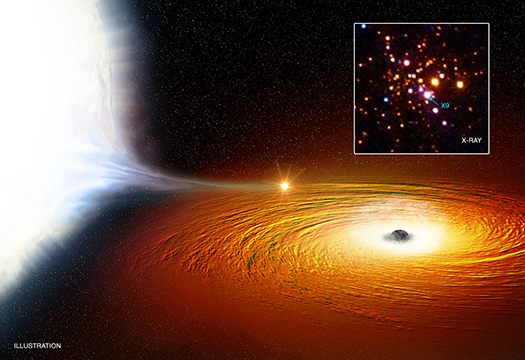

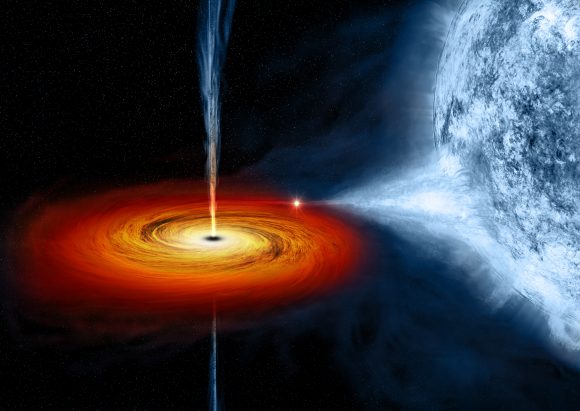

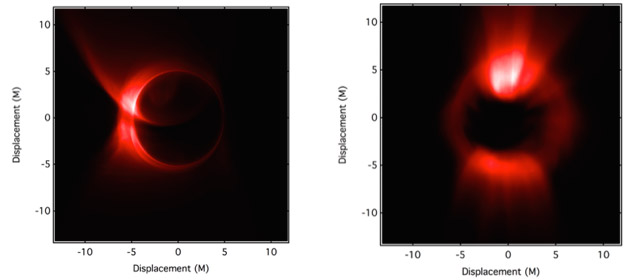

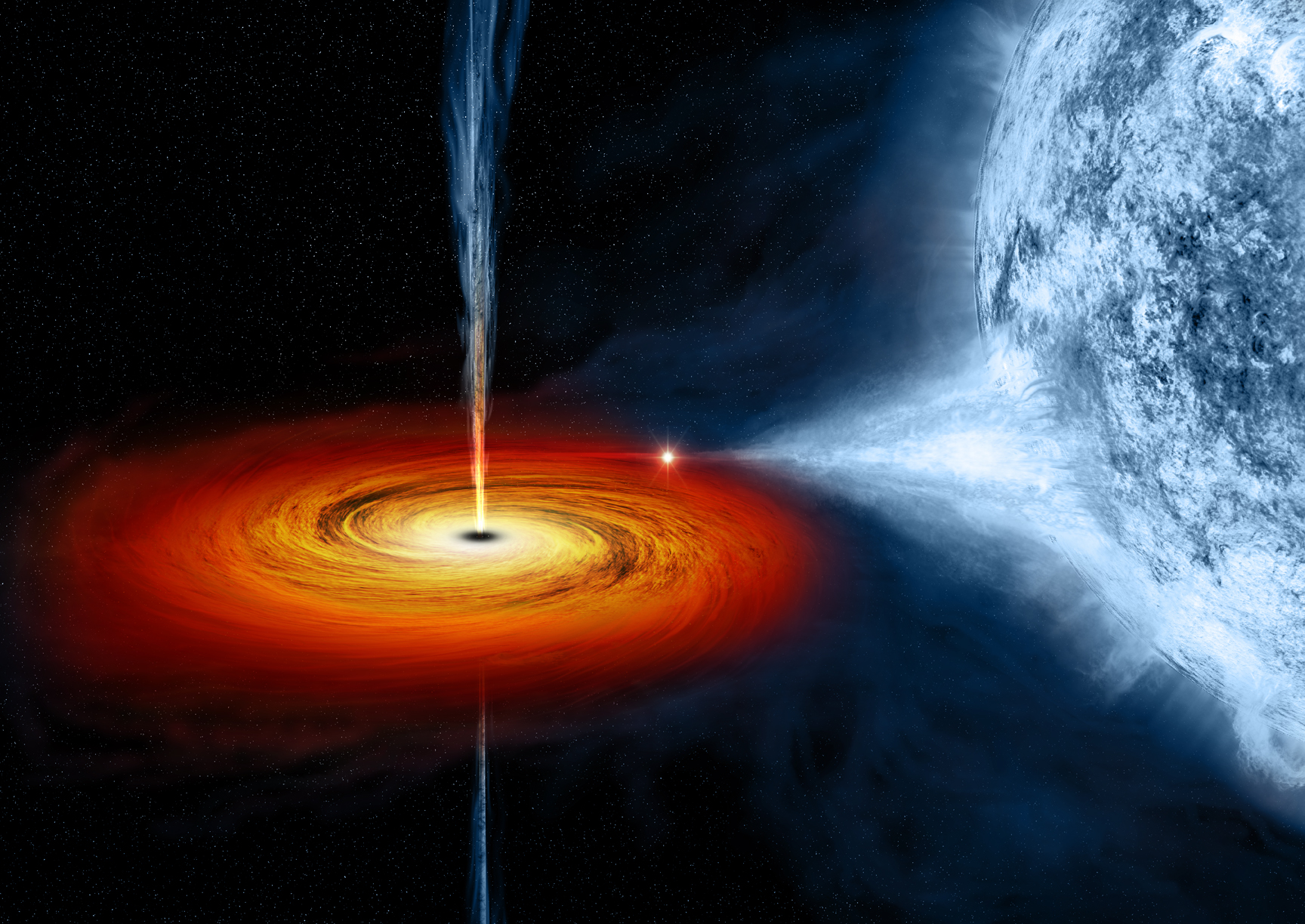

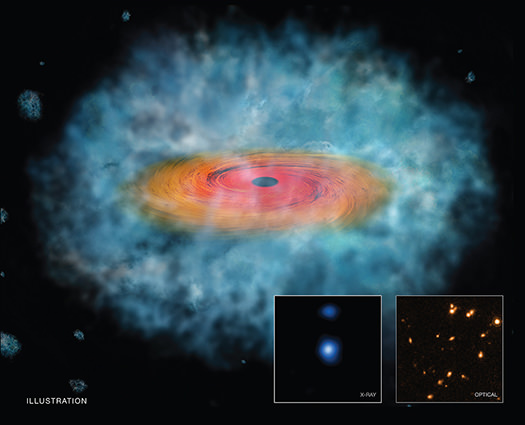

Imagine being caught in the clutches of a black hole, being whirled around at dizzying speeds and having your mass slowly but continually sucked away. That’s the life of a white dwarf star that is doing an orbital dance with a black hole. And this dancing duo could be the first ultracompact black hole X-ray binary identified in our galaxy.

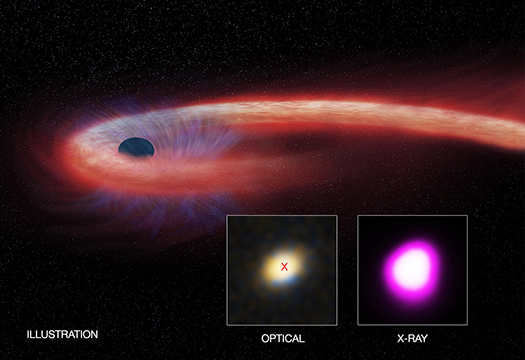

“This white dwarf is so close to the black hole that material is being pulled away from the star and dumped onto a disk of matter around the black hole before falling in,” said Arash Bahramian from the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Canada, and Michigan State University, first author of a new paper.

If you were the white dwarf in this predicament, you may wish for a quick end to it all. But somehow, the star does not appear to be in danger of falling in or being torn apart by the black hole.

“We don’t think it will follow a path into oblivion, but instead will stay in orbit,” Bahramian added.

Data from the Chandra X-ray Observatory, the NuSTAR mission and the Australian Telescope Compact Array (ATCA) shows evidence that this star whips around the black hole about twice an hour, and it may be the tightest orbital dance ever witnessed for a likely black hole and a companion star.

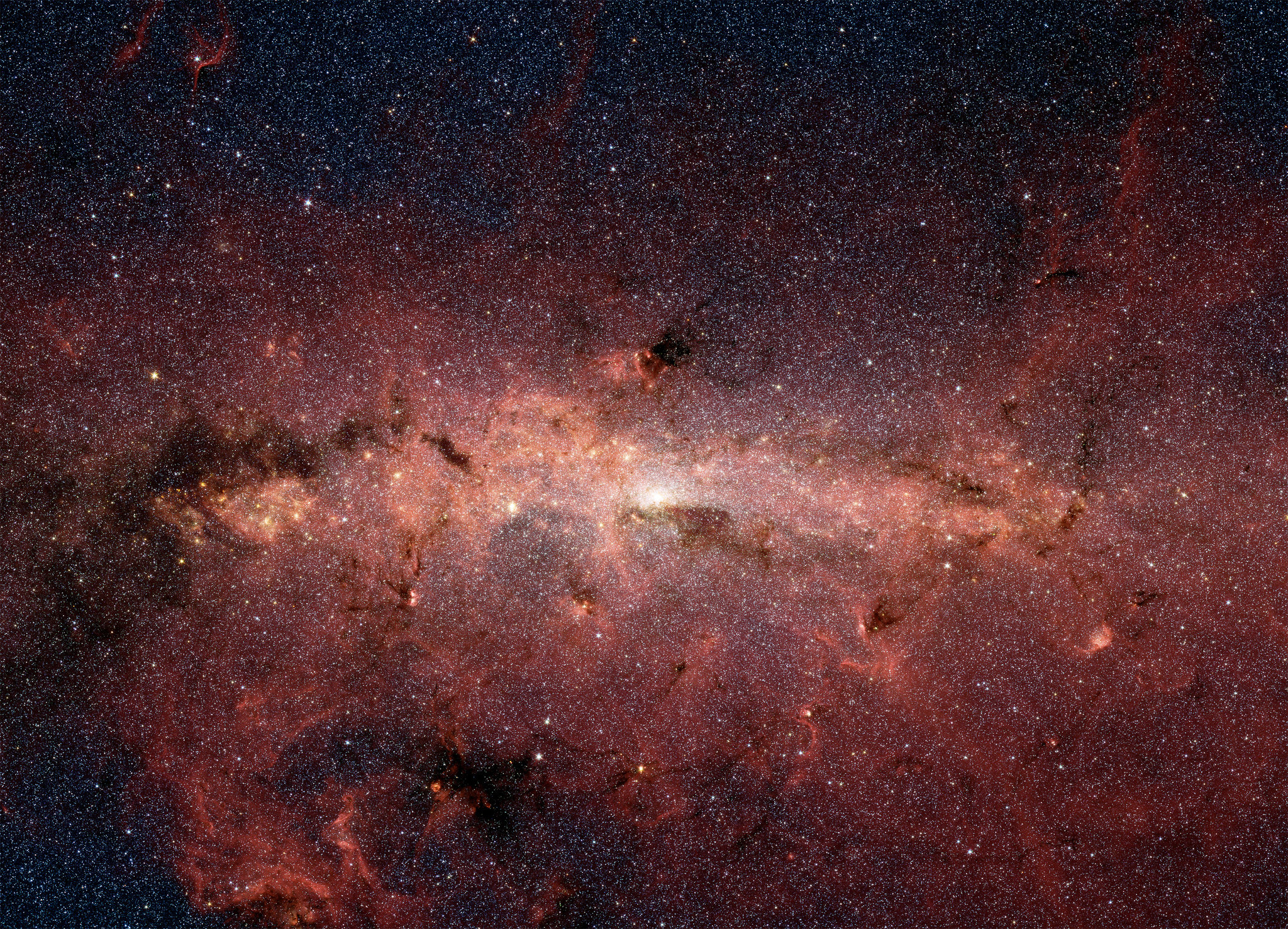

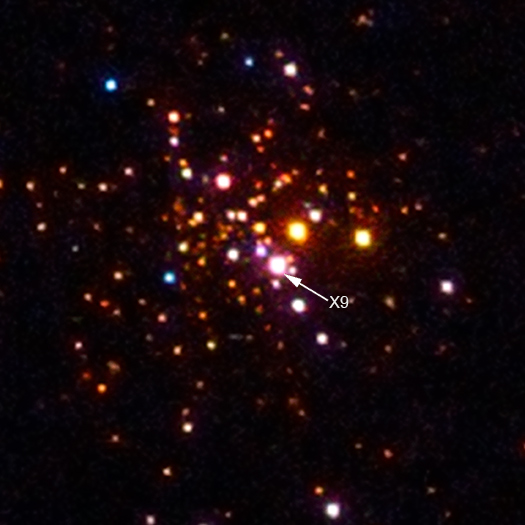

This seemingly unique binary system – with a great name, X9 — is located in the globular cluster 47 Tucanae, a dense cluster of stars in our galaxy about 14,800 light years from Earth.

Astronomers have been studying this system for a while.

“For a long time, it was thought that X9 is made up of a white dwarf pulling matter from a low mass Sun-like star,” Bahramian wrote in a blog post.

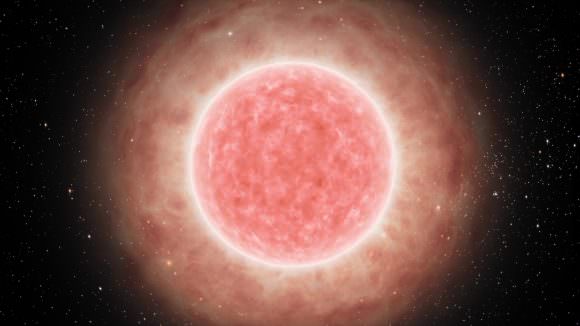

But 2015, radio observations with the ATCA showed the pair likely contains a black hole pulling material from a companion star called a white dwarf, a low-mass star that has exhausted most or all of its nuclear fuel.

“In 2015, Dr. Miller-Jones and collaborators observed strong radio emission from X9 indicating the presence of a black hole in this binary,” Bahramian continued. “They suggested that this might mean the system is made up of a black hole pulling matter from a white dwarf.”

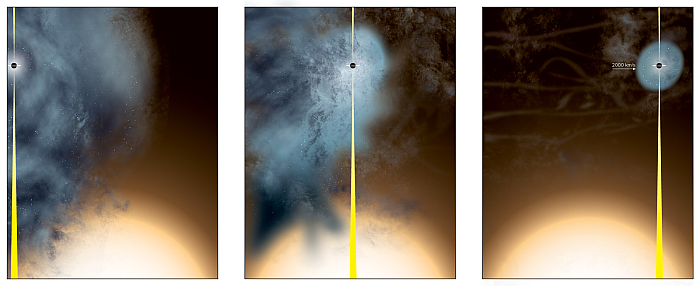

Looking at archived Chandra data, it showed changes in X-ray brightness in the same manner every 28 minutes, and Bahramian and his PhD supervisor Craig Heink think this is likely the length of time it takes the companion star to make one complete orbit around the black hole. Chandra data also shows evidence for large amounts of oxygen in the system, a characteristic feature of white dwarfs. They feel a strong case can be made that the companion star is a white dwarf. And this star would then be orbiting the black hole at just 2.5 times the distance between the Earth and the Moon.

“Eventually so much matter may be pulled away from the white dwarf that it ends up only having the mass of a planet,” said Heinke, also of the University of Alberta. “If it keeps losing mass, the white dwarf may completely evaporate.”

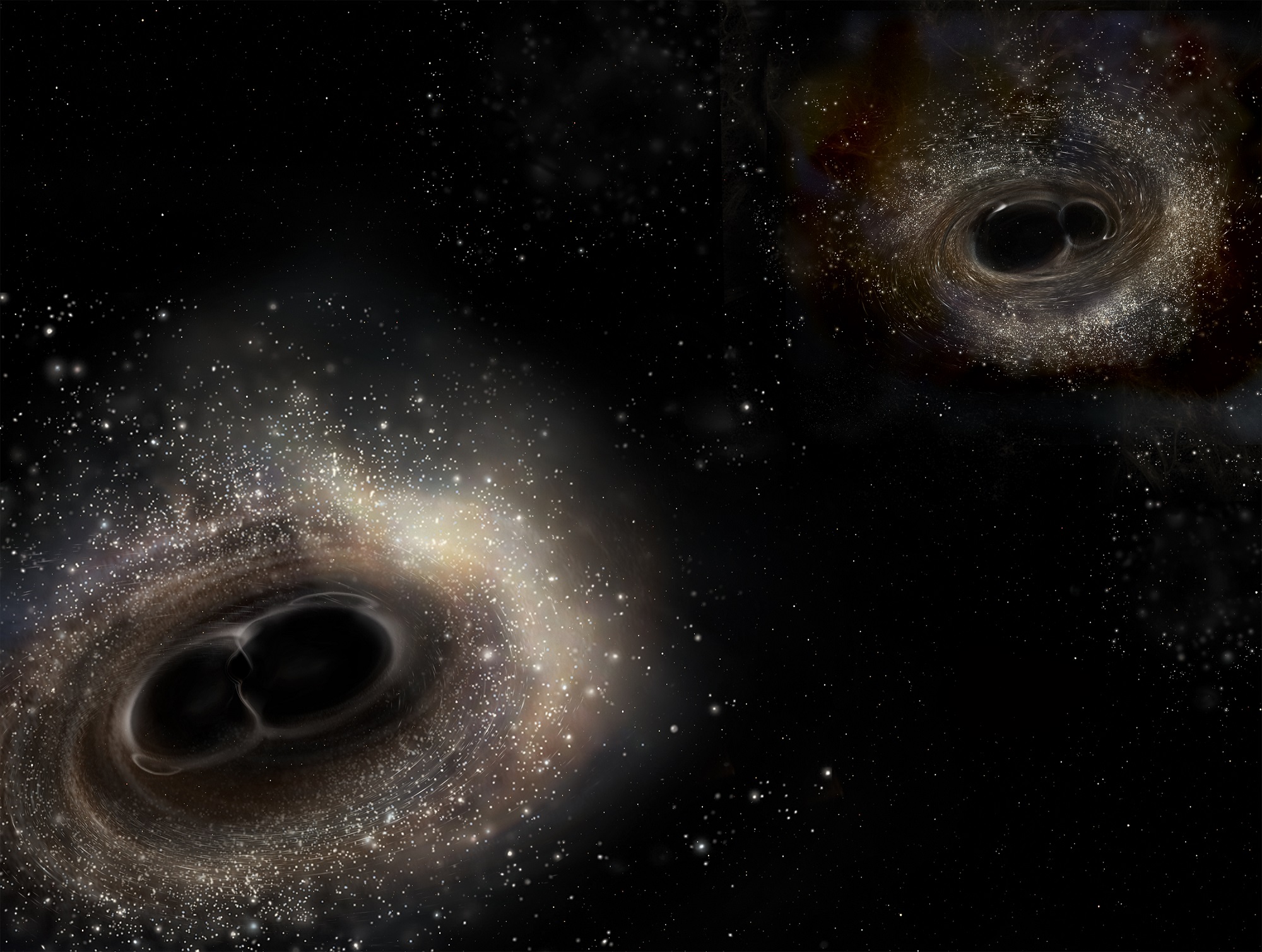

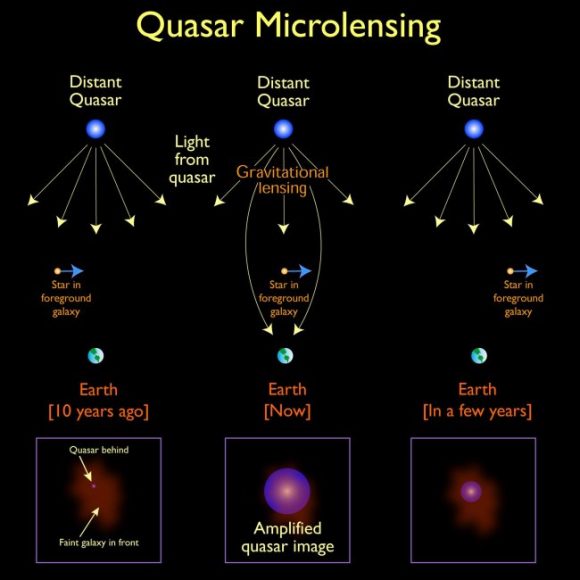

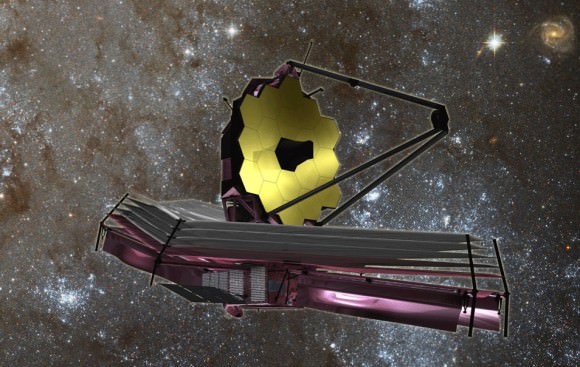

The researchers think this system would be a good candidate for future gravitational wave observatories to observe. It has to low of a frequency that is too low to be detected with Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory, LIGO, that made ground-breaking detections of gravitational waves last year. Systems like this could tell us more about gravitational waves, as well as providing more information about black hole binary systems.

“We’re going to watch this binary closely in the future, since we know little about how such an extreme system should behave”, said co-author Vlad Tudor of Curtin University and the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research in Perth, Australia. “We’re also going to keep studying globular clusters in our galaxy to see if more evidence for very tight black hole binaries can be found.”

Further reading:

Chandra press release

ICRAR press release

Blog post

Paper: The ultracompact nature of the black hole candidate X-ray binary 47 Tuc X9