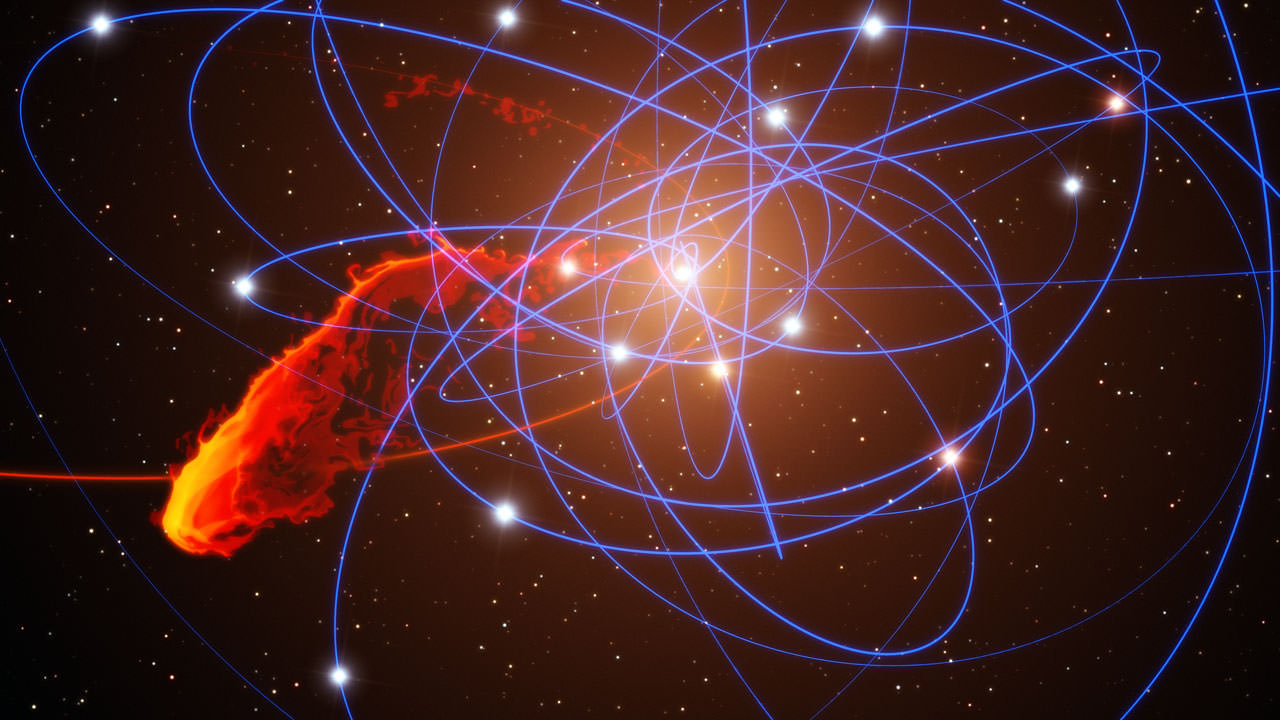

In a galaxy four billion light-years away, three supermassive black holes are locked in a whirling embrace. It’s the tightest trio of black holes known to date and even suggests that these closely packed systems are more common than previously thought.

“What remains extraordinary to me is that these black holes, which are at the very extreme of Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, are orbiting one another at 300 times the speed of sound on Earth,” said lead author Roger Deane from the University of Cape Town in a press release.

“Not only that, but using the combined signals from radio telescopes on four continents we are able to observe this exotic system one third of the way across the Universe. It gives me great excitement as this is just scratching the surface of a long list of discoveries that will be made possible with the Square Kilometer Array.”

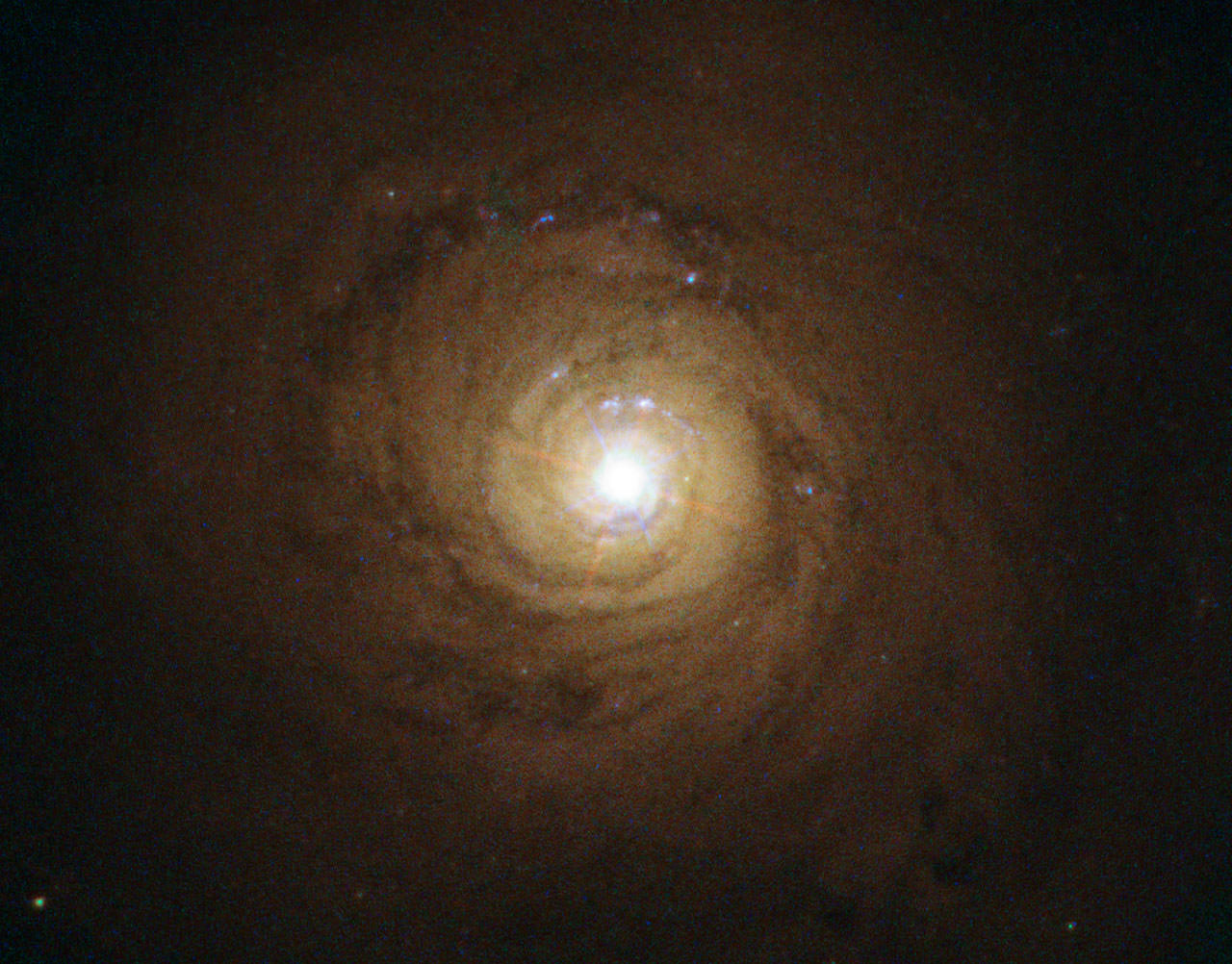

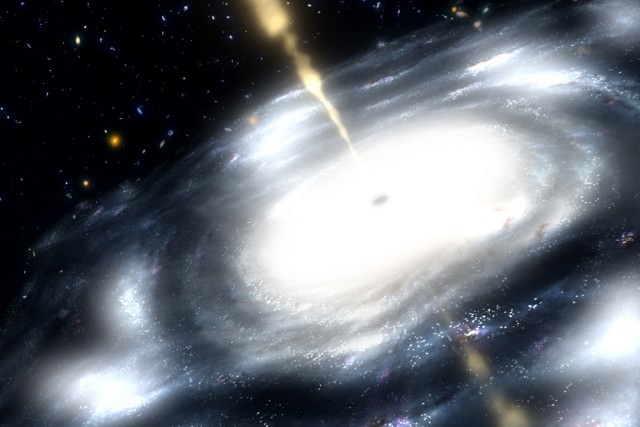

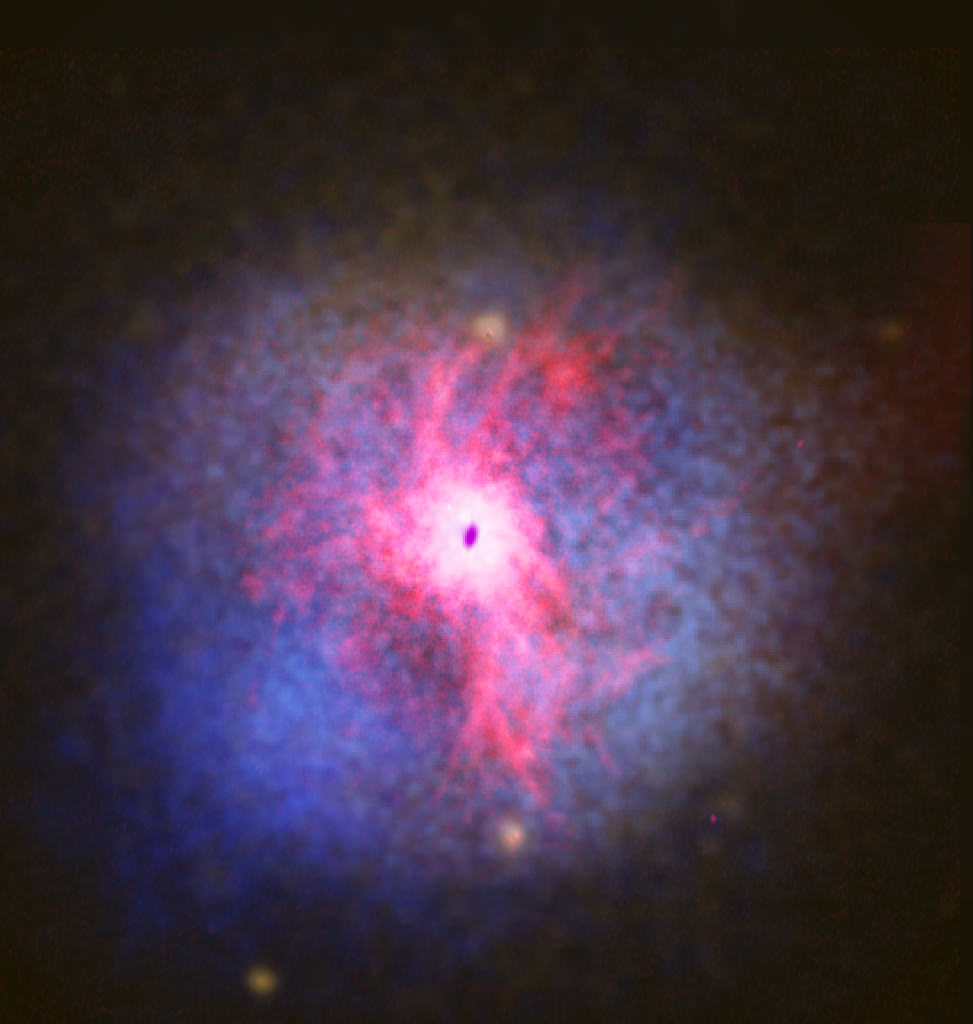

The system, dubbed SDSS J150243.091111557.3, was first identified as a quasar — a supermassive black hole at the center of a galaxy, which is rapidly accreting material and shining brightly — four years ago. But its spectrum was slightly wacky with its doubly ionized oxygen emission line [OIII] split into two peaks instead of one.

A favorable explanation suggested there were two active supermassive black holes hiding in the galaxy’s core.

An active galaxy typically shows single-peaked narrow emission lines, which stem from a surrounding region of ionized gas, Deane told Universe Today. The fact that this active galaxy shows double-peaked emission lines, suggests there are two surrounding regions of ionized gas and therefore two active supermassive black holes.

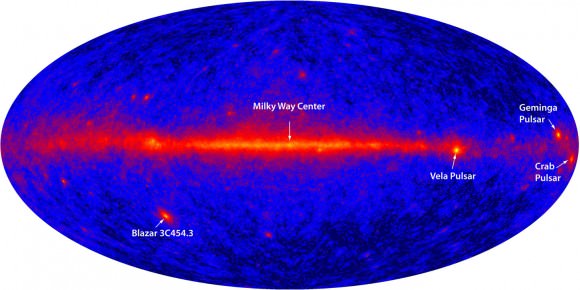

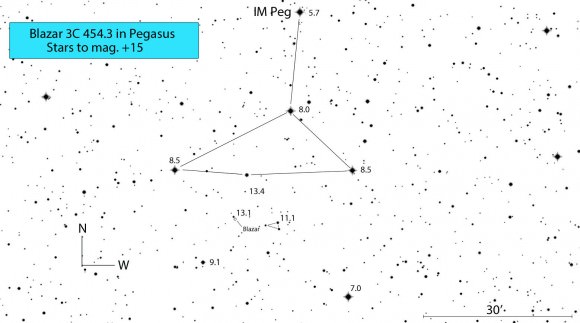

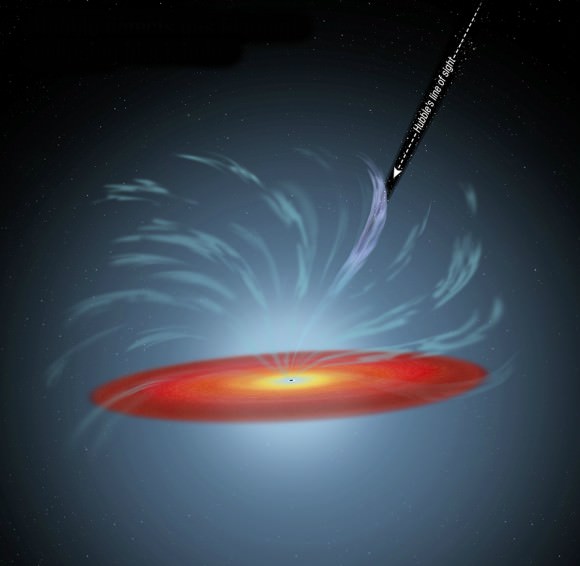

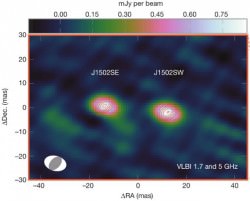

But one of the supermassive black holes was enshrouded in dust. So Deane and colleagues dug a little further. They used a technique called Very Long Baseline Interferometry (VLBI), which is a means of linking telescopes together, combining signals separated by up to 10,000 km to see detail 50 times greater than the Hubble Space Telescope.

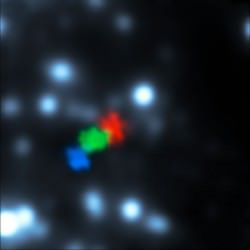

Observations from the European VLBI network — an array of European, Chinese, Russian, and South American antennas — revealed that the dust-covered supermassive black hole was once again two instead of one, making the system three supermassive black holes in total.

“This is what was so surprising,” Deane told Universe Today. “Our aim was to confirm the two suspected black holes. We did not expect one of these was in fact two, which could only be revealed by the European VLBI Network due [to the] very fine detail it is able to discern.”

Deane and colleagues looked through six similar galaxies before finding their first trio. The fact that they found one so quickly suggests that they’re more common than previously thought.

Before today, only four triple black hole systems were known, with the closest pair being 2.4 kiloparsecs apart — roughly 2,000 times the distance from Earth to the nearest star, Proxima Centauri. But the closest pair in this trio is separated by only 140 parsecs — roughly 10 times that same distance.

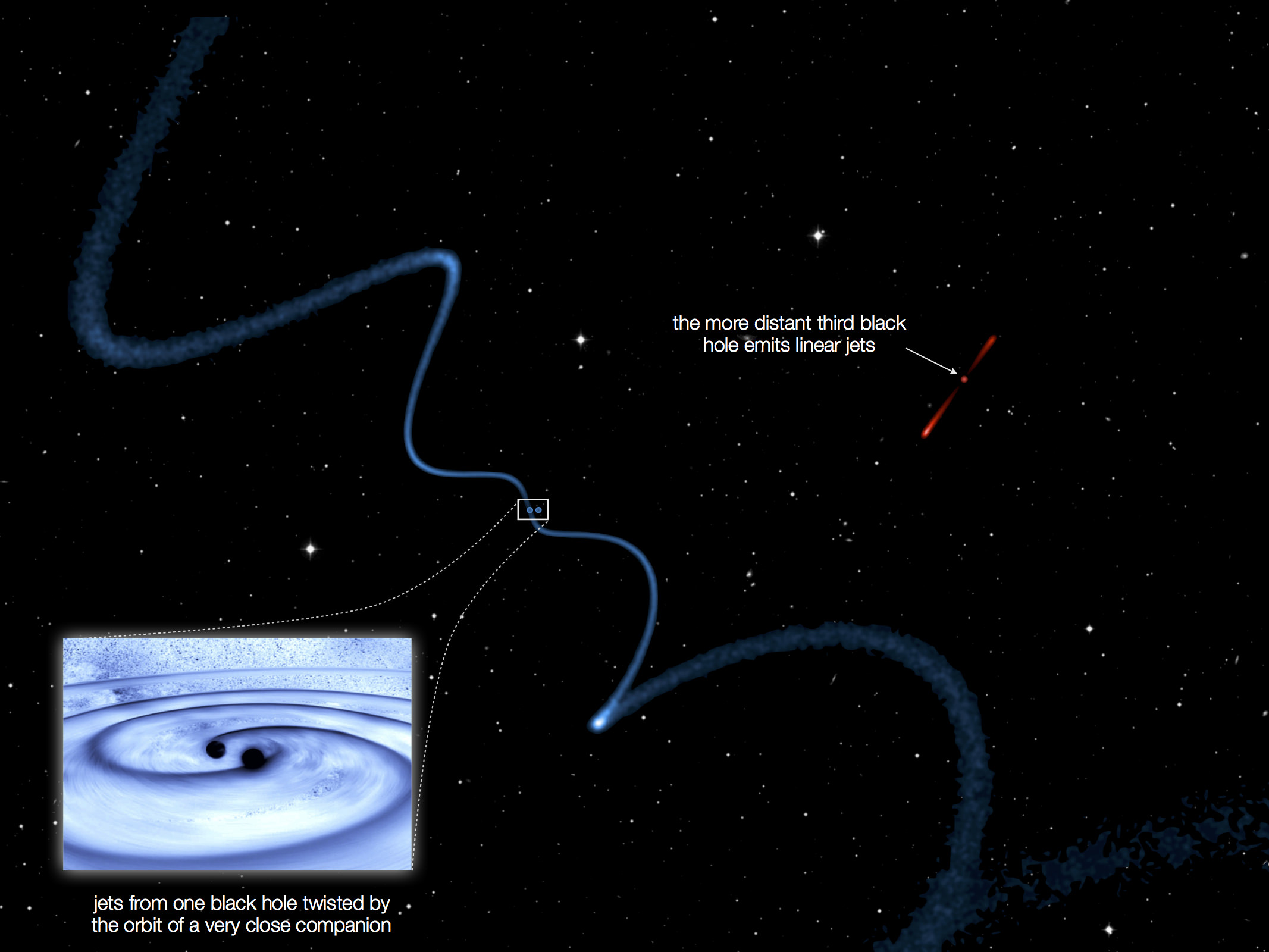

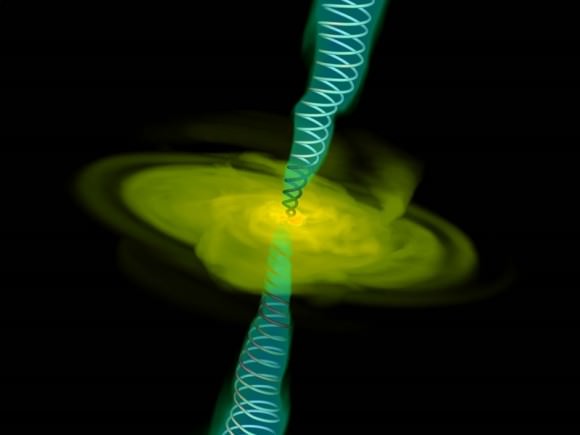

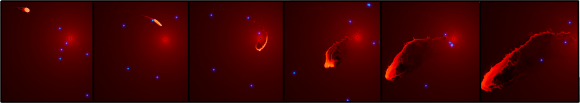

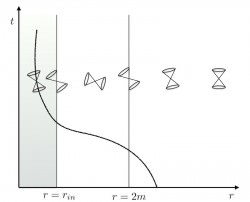

Although Deane and colleagues relied on the phenomenal resolution of the VLBI technique in order to spatially separate the two close-in black holes, they also showed that their presence could be inferred from larger-scale features. The orbital motion of the black hole, for instance, is imprinted on its large jets, twisting them into a helical-like shape. This may provide smaller telescopes with a tool to find them with much greater efficiency.

“If the result holds up, it’ll be very cool,” binary supermassive black hole expert Jessie Runnoe from Pennsylvania State University told Universe Today. This research has multiple implications for understanding further phenomena.

The first sheds light on galaxy evolution. Two or three supermassive black holes are the smoking gun that the galaxy has merged with another. So by looking at these galaxies in detail, astronomers can understand how galaxies have evolved into their present-day shapes and sizes.

The second sheds light on a phenomenon known as gravitational radiation. Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity predicts that when one of the two or three supermassive black holes spirals inward, gravitational waves — ripples in the fabric of space-time itself — propagate out into space.

Future radio telescopes should be able to measure gravitational waves from such systems as their orbits decay.

“Further in the future, the Square Kilometer Array will allow us to find and study these systems in exquisite detail, and really allow us [to] gain a much better understanding of how black holes shape galaxies over the history of the Universe,” said coauthor Matt Jarvis from the Universities of Oxford and Western Cape.

The research was published today in the journal Nature.