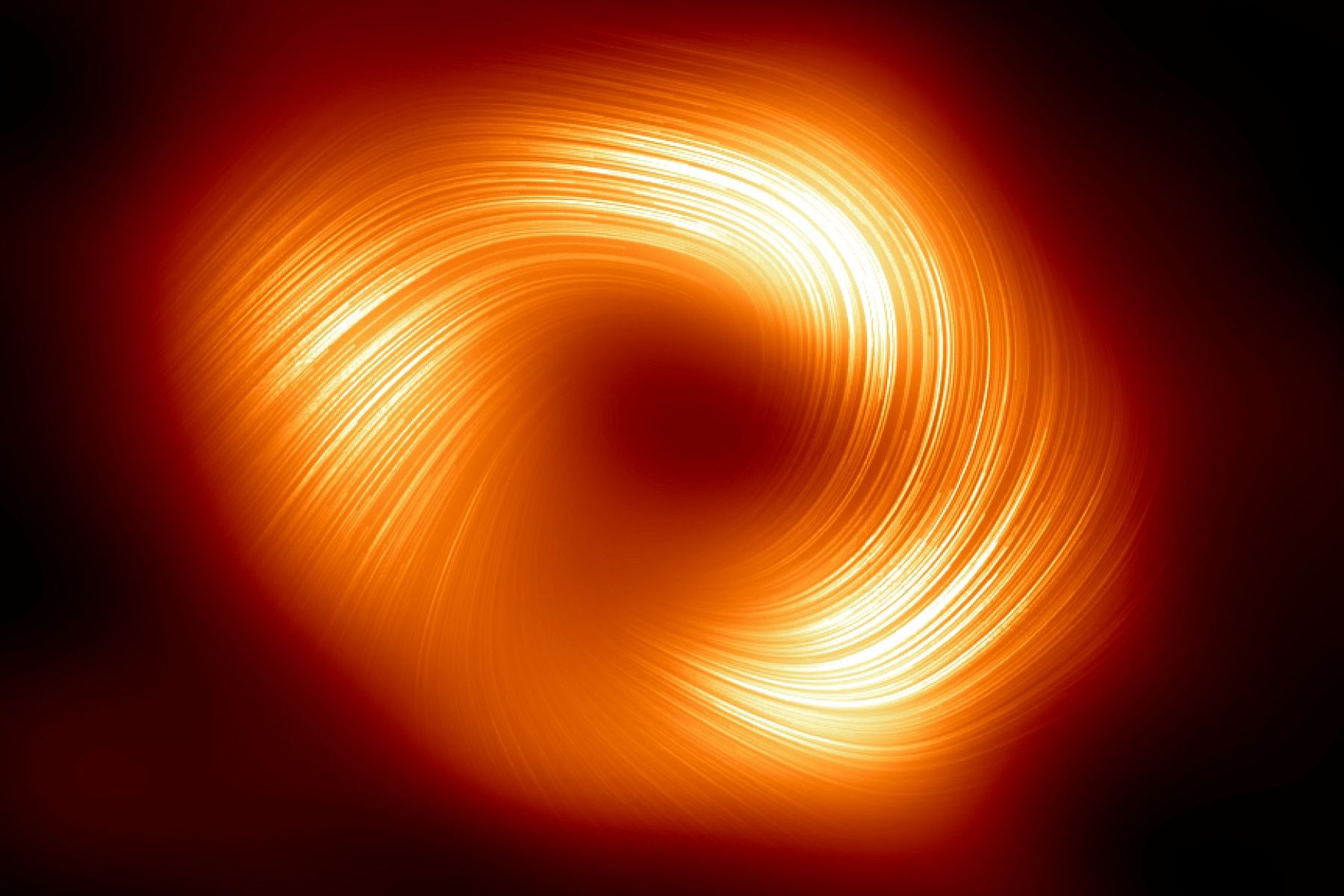

In 1974, astronomers Bruce Balick and Robert L. Brown discovered a powerful radio source at the center of the Milky Way galaxy. The source, Sagittarius A*, was subsequently revealed to be a supermassive black hole (SMBH) with a mass of over 4 million Suns. Since then, astronomers have determined that SMBHs reside at the center of all galaxies with highly active central regions known as active galactic nuclei (AGNs) or “quasars.” Despite all we’ve learned, the origin of these massive black holes remains one of the biggest mysteries in astronomy.

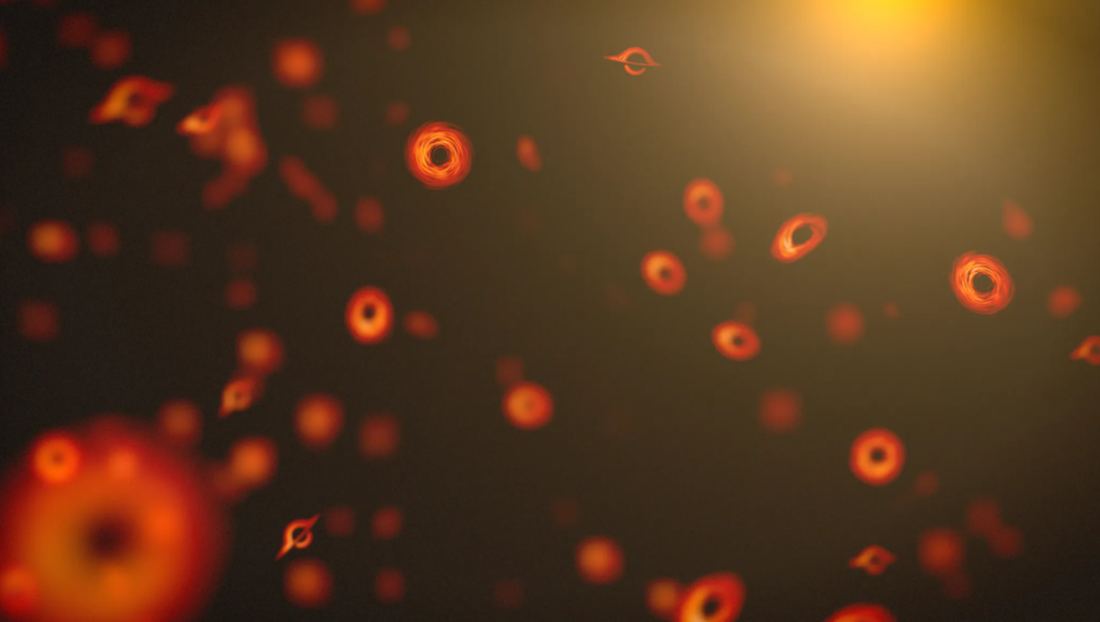

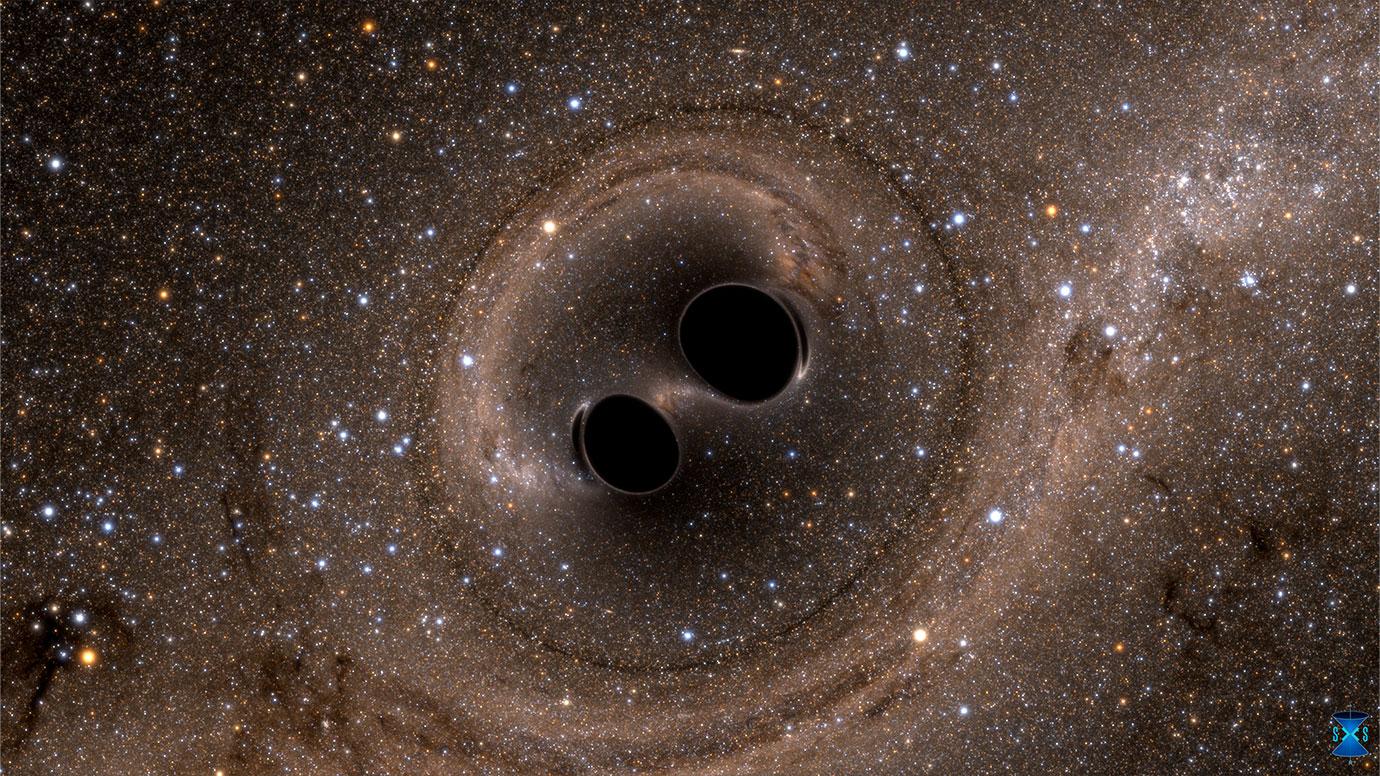

The most popular theories are that they may have formed when the Universe was still very young or have grown over time by consuming the matter around them (accretion) and through mergers with other black holes. In recent years, research has shown that when mergers between such massive objects occur, Gravitational Waves (GWs) are released. In a recent study, an international team of astrophysicists proposed a novel method for detecting pairs of SMBHs: analyzing gravitational waves generated by binaries of nearby small stellar black holes.

Continue reading “Scientists Develop a Novel Method for Detecting Supermassive Black Holes: Use Smaller Black Holes!”