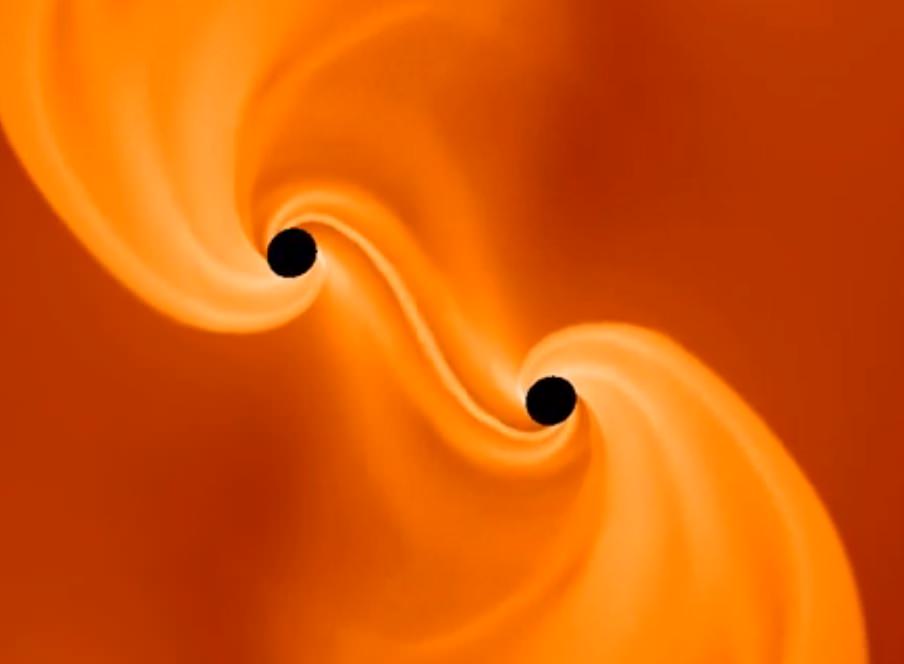

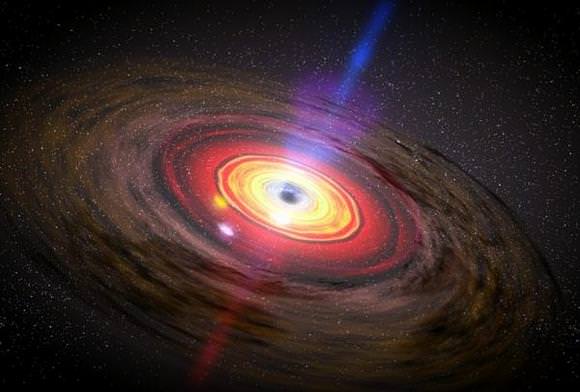

Jets of high energy particles emanating from a black hole have been detected plenty of times before, but in other galaxies, that is — not from the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way, known as Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*). Previous studies and other evidence suggested that perhaps there were jets – or ghosts of past jets – but many findings and studies often contradicted each other, and none were considered definitive.

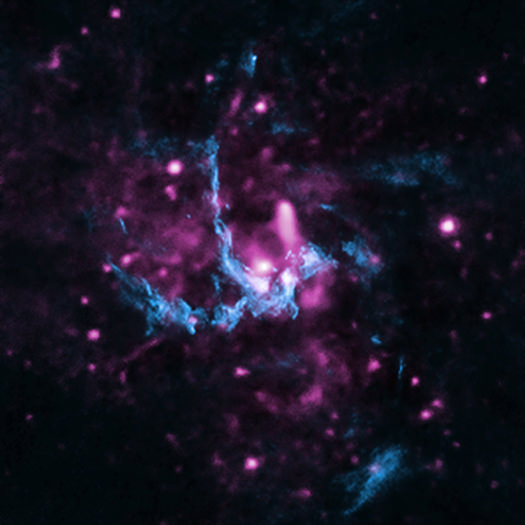

Now, astronomers using Chandra X-ray Observatory and the Very Large Array (VLA) radio telescope have found strong evidence Sgr A* is producing a jet of high-energy particles.

“For decades astronomers have looked for a jet associated with the Milky Way’s black hole. Our new observations make the strongest case yet for such a jet,” said Zhiyuan Li of Nanjing University in China, lead author of a study in The Astrophysical Journal.

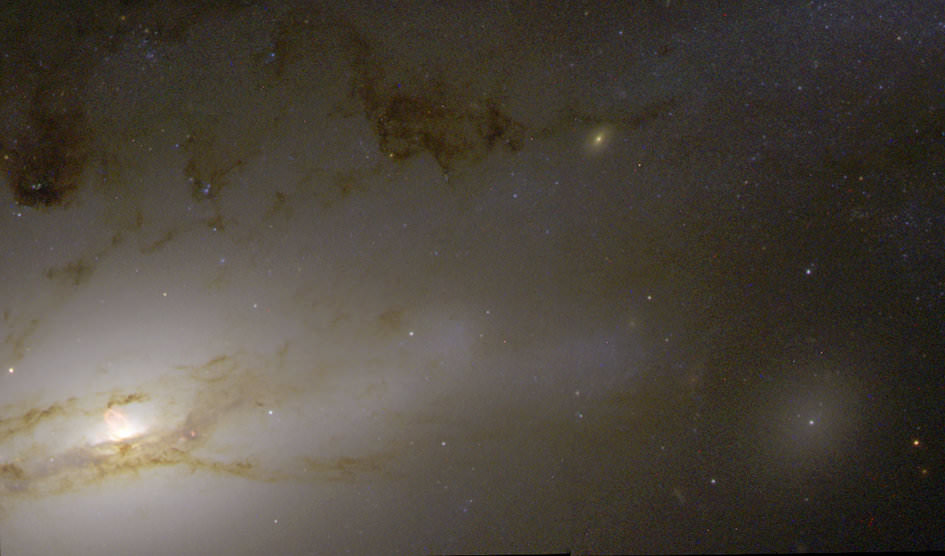

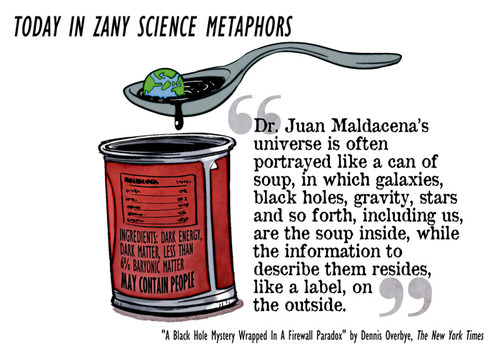

The supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way is about four million times more massive than our Sun and lies about 26,000 light-years from Earth.

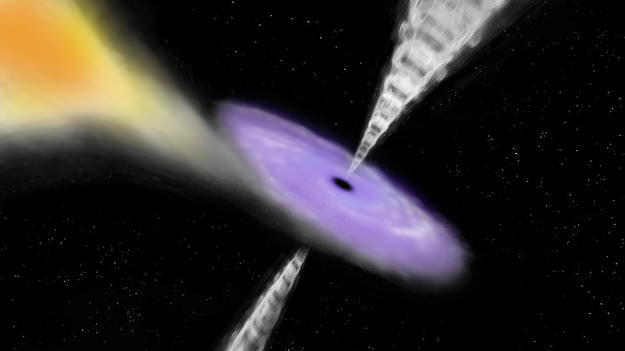

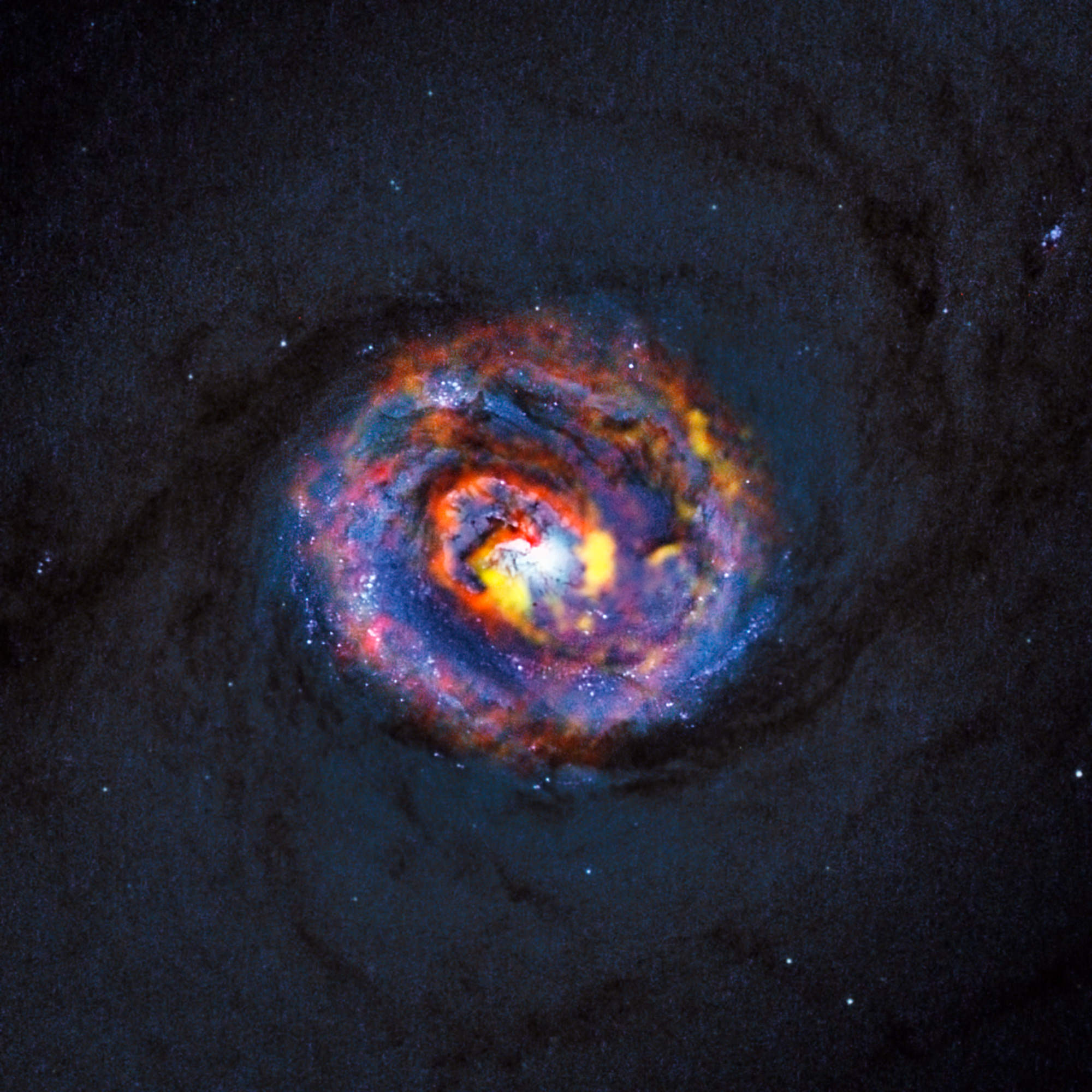

While the common notion is that black holes inhale and ingest everything that comes their way, that’s not always true. Sometimes they reject small portions of incoming mass, pushing it away in the form of a powerful jet, and many times a pair of jets. These jets also feed the surroundings, releasing both mass and energy and likely play important roles in regulating the rate of formation of new stars.

Sgr A* is presently known to be consuming very little material, and so the jet is weak, making it difficult to detect. Astronomers don’t see another jet “shooting” in the opposite direction but that may be because of gas or dust blocking the line of sight from Earth or a lack of material to fuel the jet. Or there may be just a single jet.

“We were very eager to find a jet from Sgr A* because it tells us the direction of the black hole’s spin axis. This gives us important clues about the growth history of the black hole,” said Mark Morris of the University of California at Los Angeles, a co-author of the study.

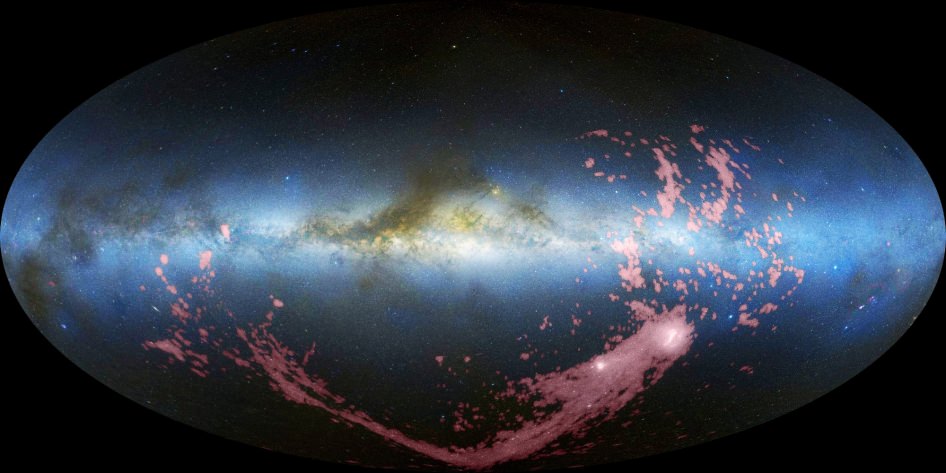

The study shows the spin axis of Sgr A* is pointing in one direction, parallel to the rotation axis of the Milky Way, which indicates to astronomers that gas and dust have migrated steadily into Sgr A* over the past 10 billion years. If the Milky Way had collided with large galaxies in the recent past and their central black holes had merged with Sgr A*, the jet could point in any direction.

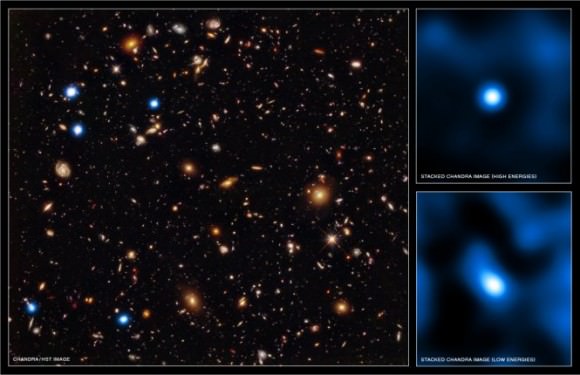

The jet appears to be running into gas near Sgr A*, producing X-rays detected by Chandra and radio emission observed by the VLA. The two key pieces of evidence for the jet are a straight line of X-ray emitting gas that points toward Sgr A* and a shock front — similar to a sonic boom — seen in radio data, where the jet appears to be striking the gas. Additionally, the energy signature, or spectrum, in X-rays of Sgr A* resembles that of jets coming from supermassive black holes in other galaxies.

The Chandra observations in this study were taken between September 1999 and March 2011, with a total exposure of about 17 days.

Source: Chandra