From a NASA press release:

NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) mission has led to a bonanza of newfound supermassive black holes and extreme galaxies called hot DOGs, or dust-obscured galaxies.

Images from the telescope have revealed millions of dusty black hole candidates across the universe and about 1,000 even dustier objects thought to be among the brightest galaxies ever found. These powerful galaxies, which burn brightly with infrared light, are nicknamed hot DOGs.

“WISE has exposed a menagerie of hidden objects,” said Hashima Hasan, WISE program scientist at NASA Headquarters in Washington. “We’ve found an asteroid dancing ahead of Earth in its orbit, the coldest star-like orbs known and now, supermassive black holes and galaxies hiding behind cloaks of dust.”

WISE scanned the whole sky twice in infrared light, completing its survey in early 2011. Like night-vision goggles probing the dark, the telescope captured millions of images of the sky. All the data from the mission have been released publicly, allowing astronomers to dig in and make new discoveries.

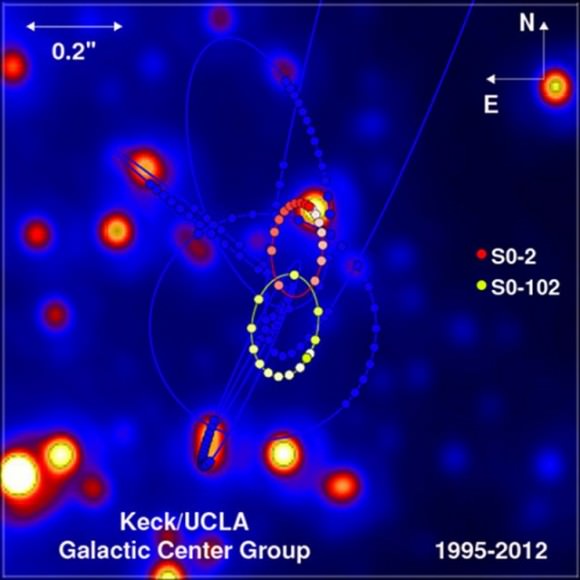

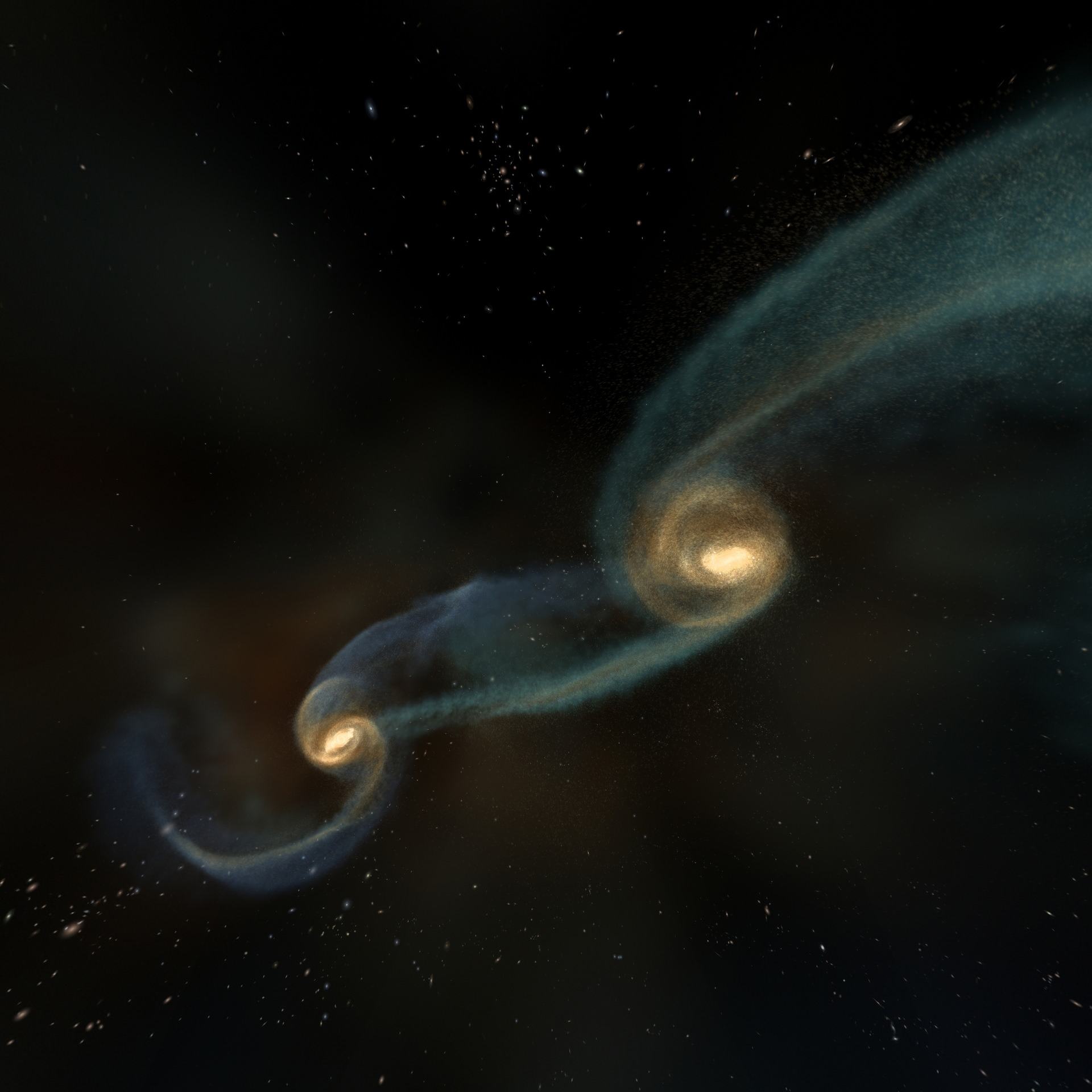

The latest findings are helping astronomers better understand how galaxies and the behemoth black holes at their centers grow and evolve together. For example, the giant black hole at the center of our Milky Way galaxy, called Sagittarius A*, has 4 million times the mass of our sun and has gone through periodic feeding frenzies where material falls towards the black hole, heats up and irradiates its surroundings. Bigger central black holes, up to a billion times the mass of our sun, may even shut down star formation in galaxies.

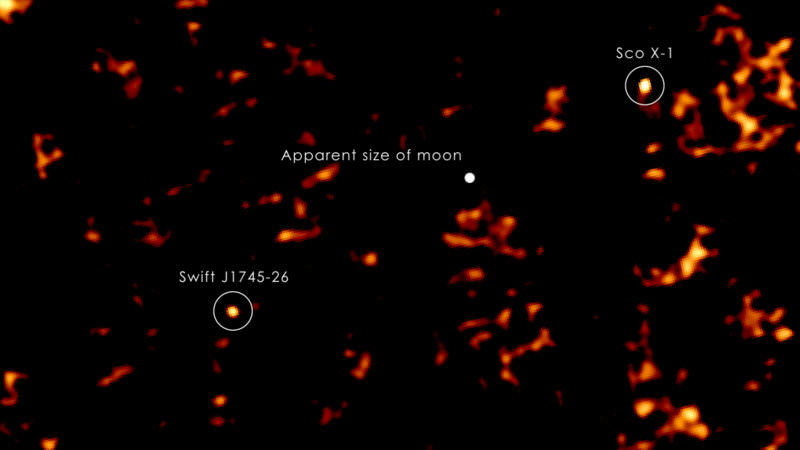

In one study, astronomers used WISE to identify about 2.5 million actively feeding supermassive black holes across the full sky, stretching back to distances more than 10 billion light-years away. About two-thirds of these objects never had been detected before because dust blocks their visible light. WISE easily sees these monsters because their powerful, accreting black holes warm the dust, causing it to glow in infrared light.

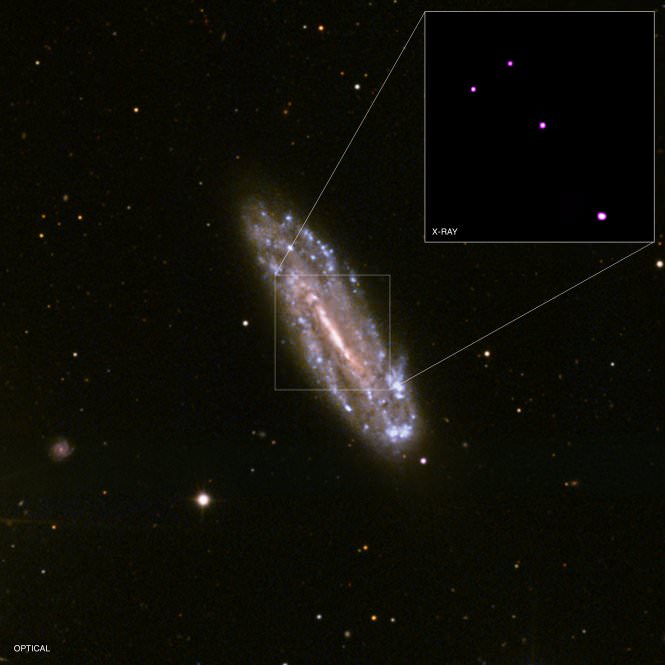

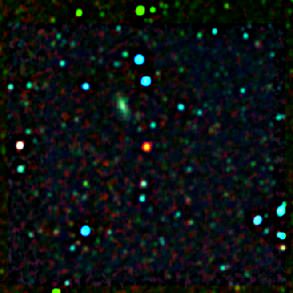

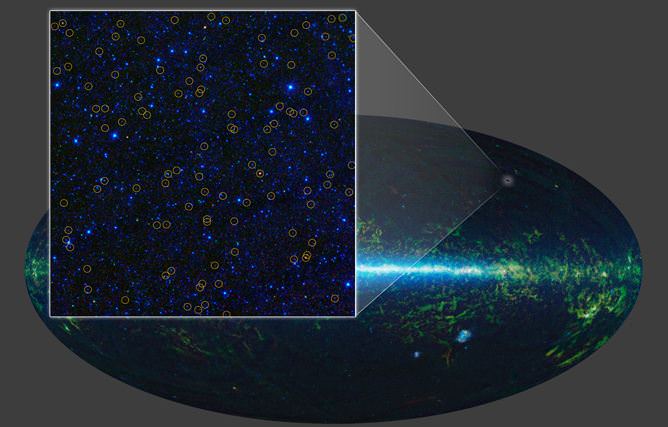

This zoomed-in view of a portion of the all-sky survey from WISE shows a collection of quasar candidates. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA

“We’ve got the black holes cornered,” said Daniel Stern of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., lead author of the WISE black hole study and project scientist for another NASA black-hole mission, the Nuclear Spectroscopic Telescope Array (NuSTAR). “WISE is finding them across the full sky, while NuSTAR is giving us an entirely new look at their high-energy X-ray light and learning what makes them tick.”

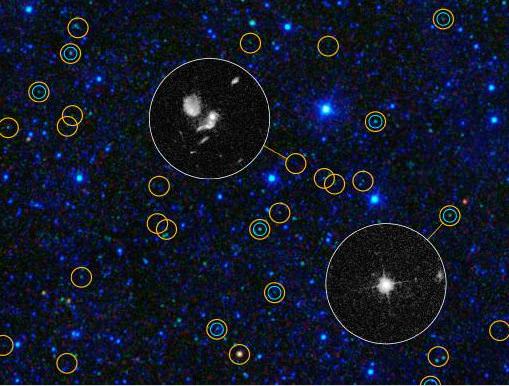

In two other WISE papers, researchers report finding what are among the brightest galaxies known, one of the main goals of the mission. So far, they have identified about 1,000 candidates.

These extreme objects can pour out more than 100 trillion times as much light as our sun. They are so dusty, however, that they appear only in the longest wavelengths of infrared light captured by WISE. NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope followed up on the discoveries in more detail and helped show that, in addition to hosting supermassive black holes feverishly snacking on gas and dust, these DOGs are busy churning out new stars.

“These dusty, cataclysmically forming galaxies are so rare WISE had to scan the entire sky to find them,” said Peter Eisenhardt, lead author of the paper on the first of these bright, dusty galaxies, and project scientist for WISE at JPL. “We are also seeing evidence that these record setters may have formed their black holes before the bulk of their stars. The ‘eggs’ may have come before the ‘chickens.'”

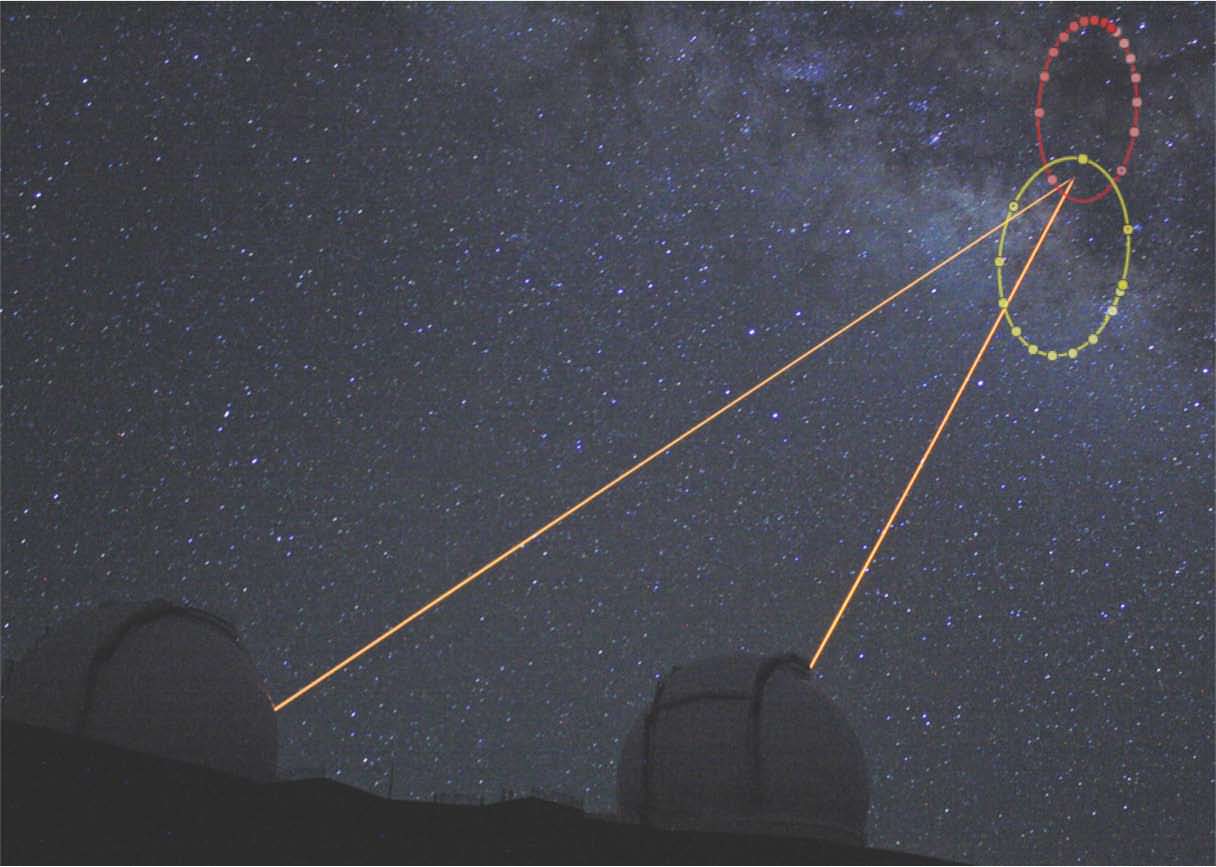

More than 100 of these objects, located about 10 billion light-years away, have been confirmed using the W.M. Keck Observatory on Mauna Kea, Hawaii, as well as the Gemini Observatory in Chile, Palomar’s 200-inch Hale telescope near San Diego, and the Multiple Mirror Telescope Observatory near Tucson, Ariz.

The WISE observations, combined with data at even longer infrared wavelengths from Caltech’s Submillimeter Observatory atop Mauna Kea, revealed that these extreme galaxies are more than twice as hot as other infrared-bright galaxies. One theory is their dust is being heated by an extremely powerful burst of activity from the supermassive black hole.

“We may be seeing a new, rare phase in the evolution of galaxies,” said Jingwen Wu of JPL, lead author of the study on the submillimeter observations. All three papers are being published in the Astrophysical Journal.

The three technical journal articles, including PDFs, can be found at http://arxiv.org/abs/1205.0811, http://arxiv.org/abs/1208.5517 and http://arxiv.org/abs/1208.5518 .

Lead image caption: With its all-sky infrared survey, NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE, has identified millions of quasar candidates. Image credit: NASA/JPL-Caltech/UCLA