[/caption]

I’m going to try and say this before the Bad Astronomer does: Holy Haleakala! A team of astronomers using the Pan-STARRS1 telescope on Mount Haleakala in Hawaii have found evidence of a black hole ripping a star to shreds. While this isn’t the first time this type of activity has been detected, these new observations are the best views so far of what happens to objects that are consumed by a black hole. Plus, astronomers, for the first time, know what kind of star was destroyed and watched as it happened. This all helps in providing more insight into how black holes behave: They aren’t enormous vacuum cleaners that suck up and destroy everything around them, or sharks that seek out and consume their victims. Instead, like Venus Fly Traps, they wait for objects to come to them.

“Black holes, like sharks, suffer from a popular misconception that they are perpetual killing machines,” said Ryan Chornock of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA). “Actually, they’re quiet for most of their lives. Occasionally a star wanders too close, and that’s when a feeding frenzy begins.”

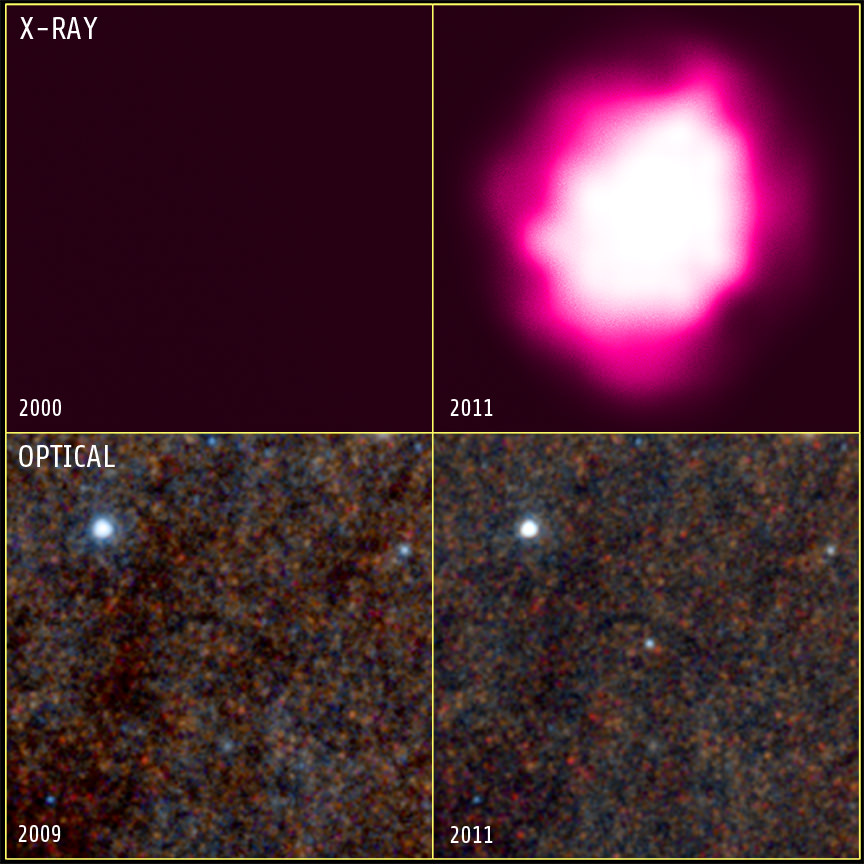

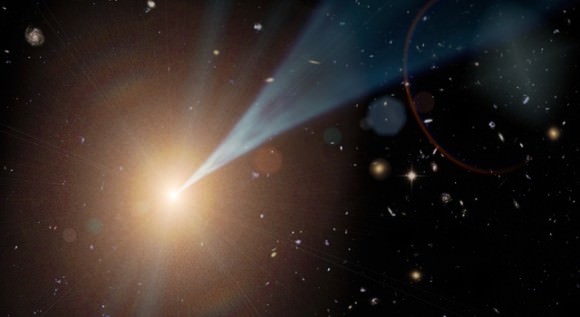

If a star passes too close to a black hole, tidal forces can rip it apart. The remaining gases then swirl in toward the black hole. But just a small fraction of the material near a black hole falls in, while most of it just circles for a while – sometimes forever. The material close the black hole gets superheated, causing it to glow. By searching for newly glowing supermassive black holes, astronomers can spot them in the midst of a feast.

So, kind of like with Junior, the giant Venus Fly Trap in the movie “Little Shop of Horrors,” the feast is evident from what doesn’t get eaten.

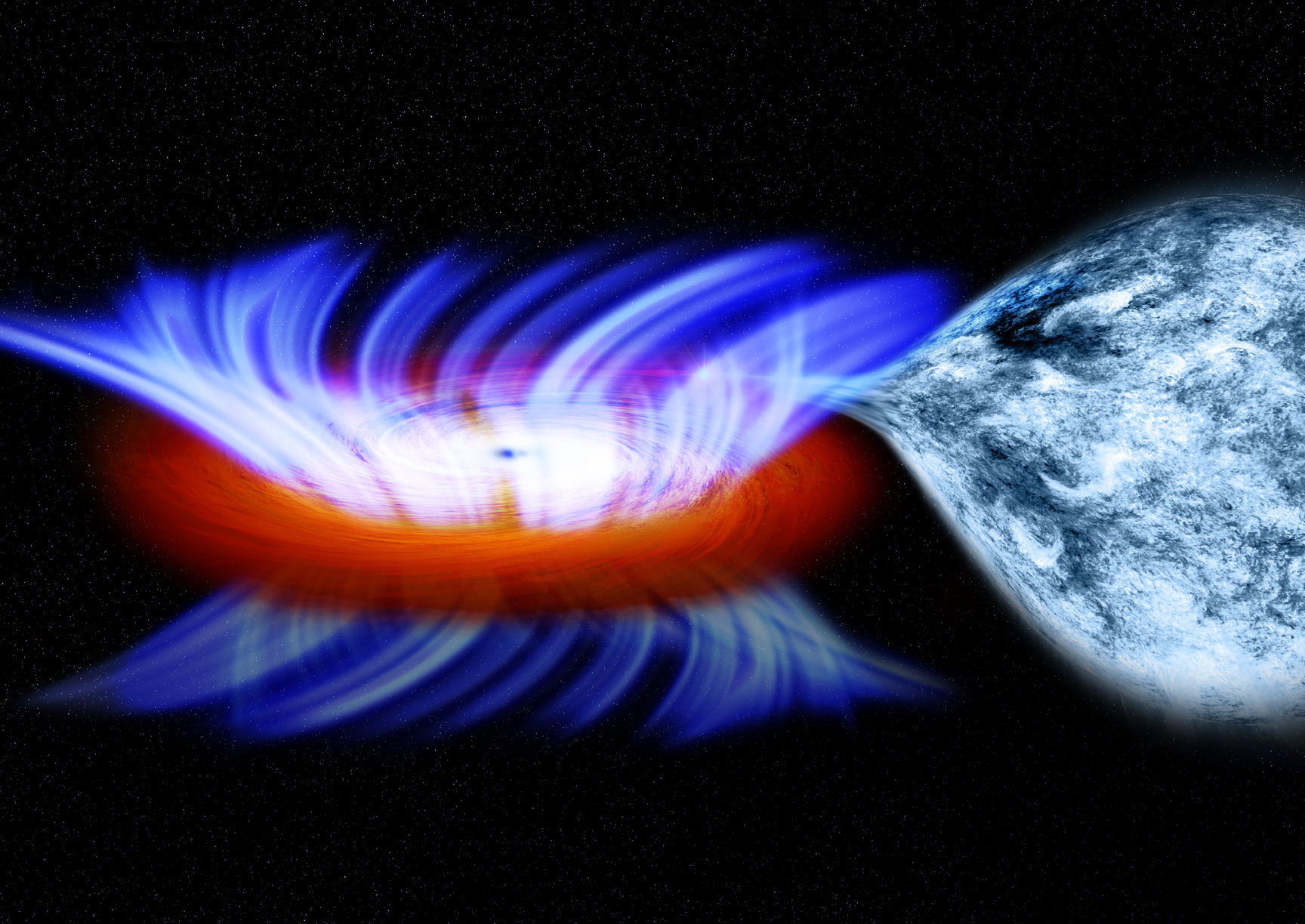

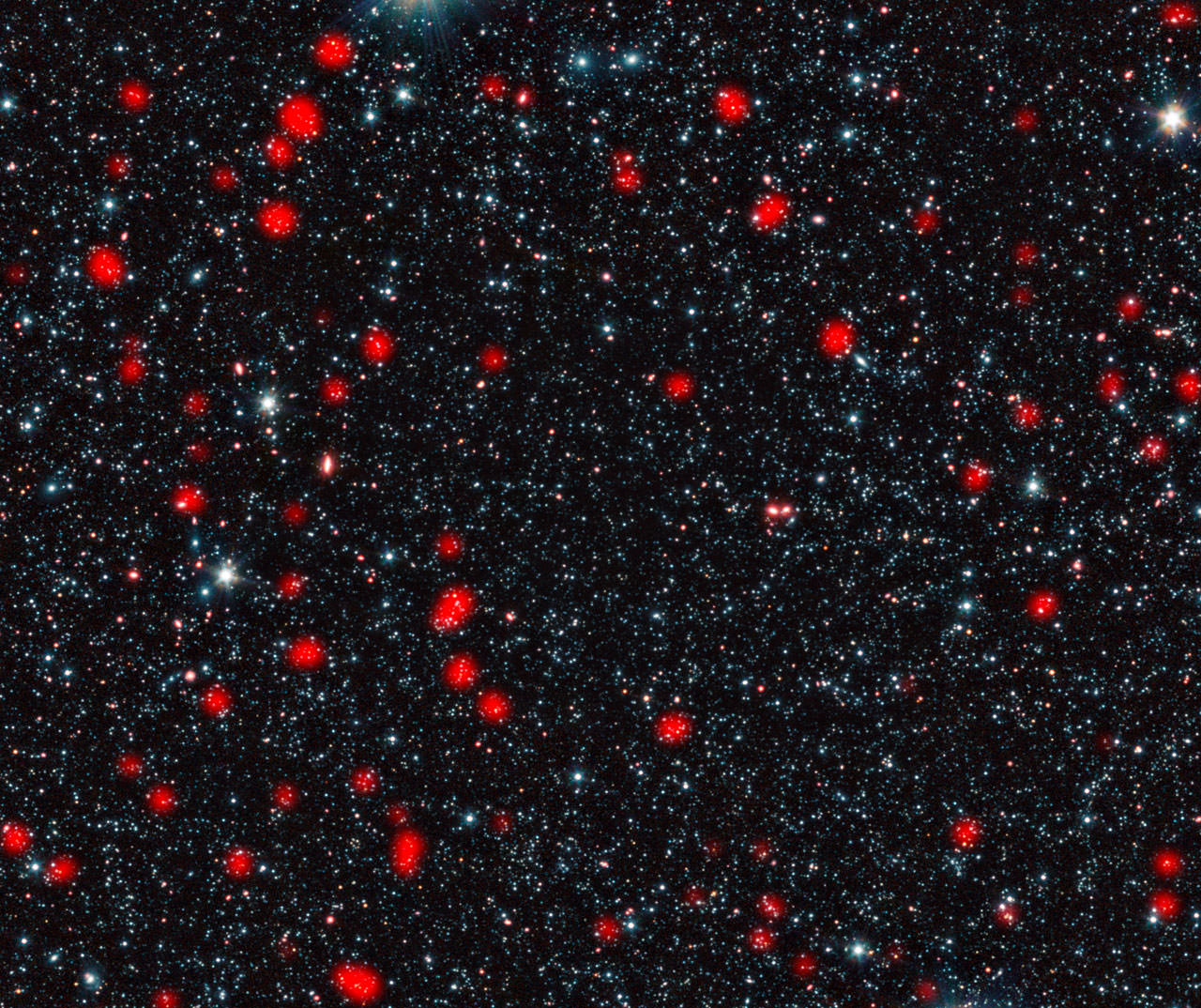

This computer simulation shows a star being shredded by the gravity of a massive black hole. Some of the stellar debris falls into the black hole and some of it is ejected into space at high speeds. The areas in white are regions of highest density, with progressively redder colors corresponding to lower-density regions. The blue dot pinpoints the black hole’s location. The elapsed time corresponds to the amount of time it takes for a Sun-like star to be ripped apart by a black hole a million times more massive than the Sun.

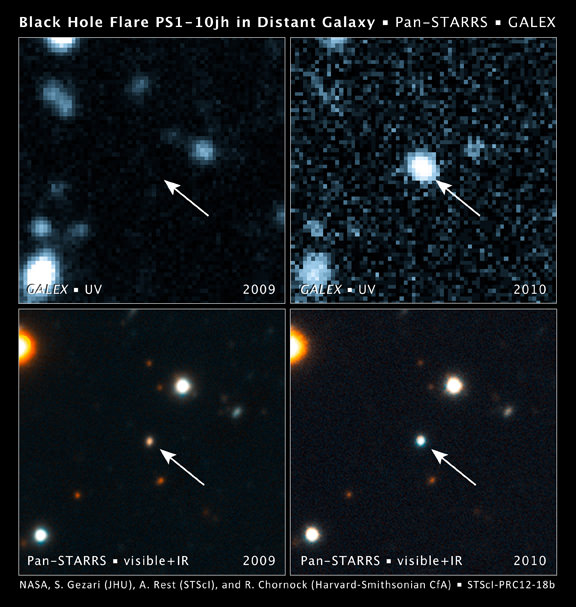

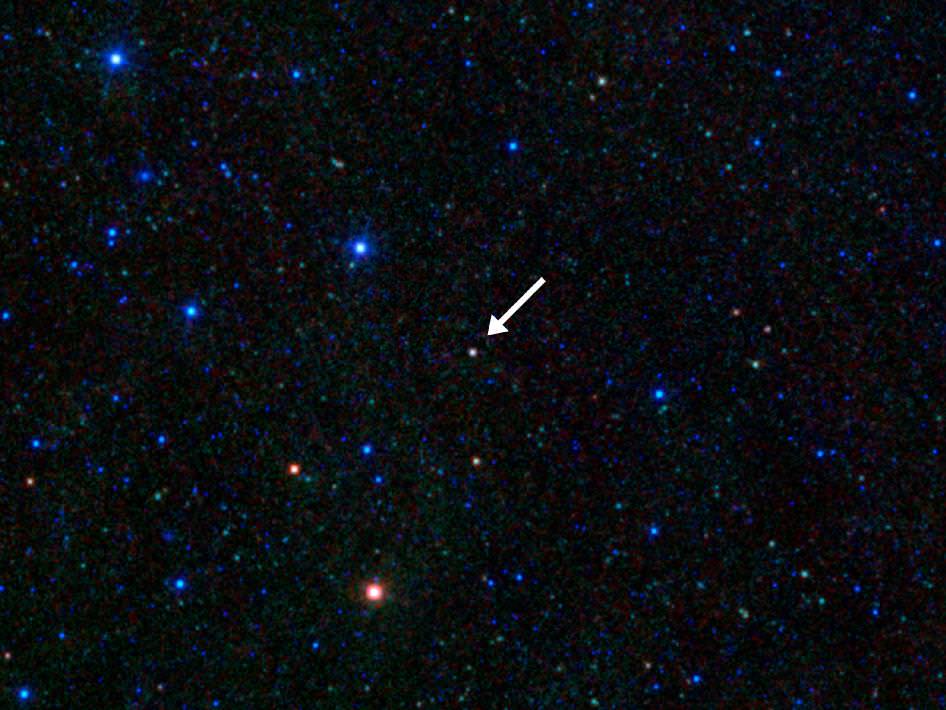

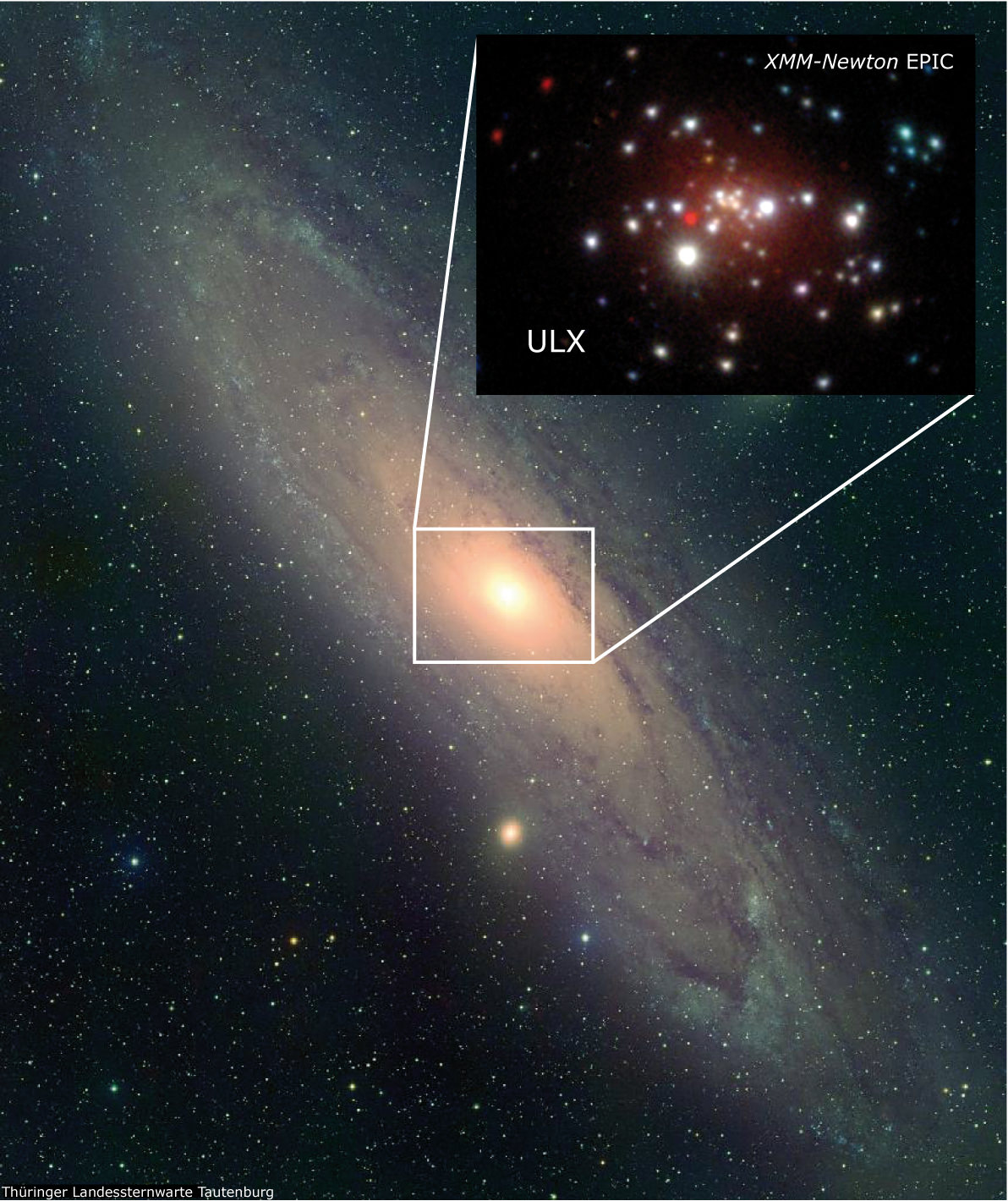

The team discovered this type of glow on May 31, 2010, with Pan-STARRS1 and also with NASA’s Galaxy Evolution Explorer (GALEX). The flare brightened to a peak on July 12th before fading away over the course of a year. The event took place in a galaxy 2.7 billion light-years away, and the black hole contains as much mass as 3 million Suns, making it about the same size as the Milky Way’s central black hole.

“We observed the demise of a star and its digestion by the black hole in real time,” said Harvard co-author Edo Berger.

“We’re also witnessing the spectral signature of the ejected gas, said Suvi Gezari of The Johns Hopkins University who lead the research, “which we find to be mostly helium. It is like we are gathering evidence from a crime scene. Because there is very little hydrogen and mostly helium in the gas we detect from the carnage, we know that the slaughtered star had to have been the helium-rich core of a stripped star.”

Follow-up observations with the MMT Observatory in Arizona showed that the black hole was consuming large amounts of helium. Therefore, the shredded star likely was the core of a red giant star. The lack of hydrogen showed this is likely not the first time the star had encountered the same black hole, and that it lost its outer atmosphere on a previous pass.

The star may have been near the end of its life, the astronomers say. After consuming most of its hydrogen fuel, it had probably ballooned in size, becoming a red giant. The astronomers think the bloated star was looping around the black hole in a highly elliptical orbit, similar to a comet’s elongated orbit around the Sun.

“This is the first time where we have so many pieces of evidence, and now we can put them all together to weigh the perpetrator (the black hole) and determine the identity of the unlucky star that fell victim to it,” Gezari said. “These observations also give us clues to what evidence to look for in the future to find this type of event.”

The team’s results were published today in the online edition of the journal Nature.

Nature Science Paper by S. Gezari et al. (PDF document)

Sources: Harvard Smithsonian CfA, NASA