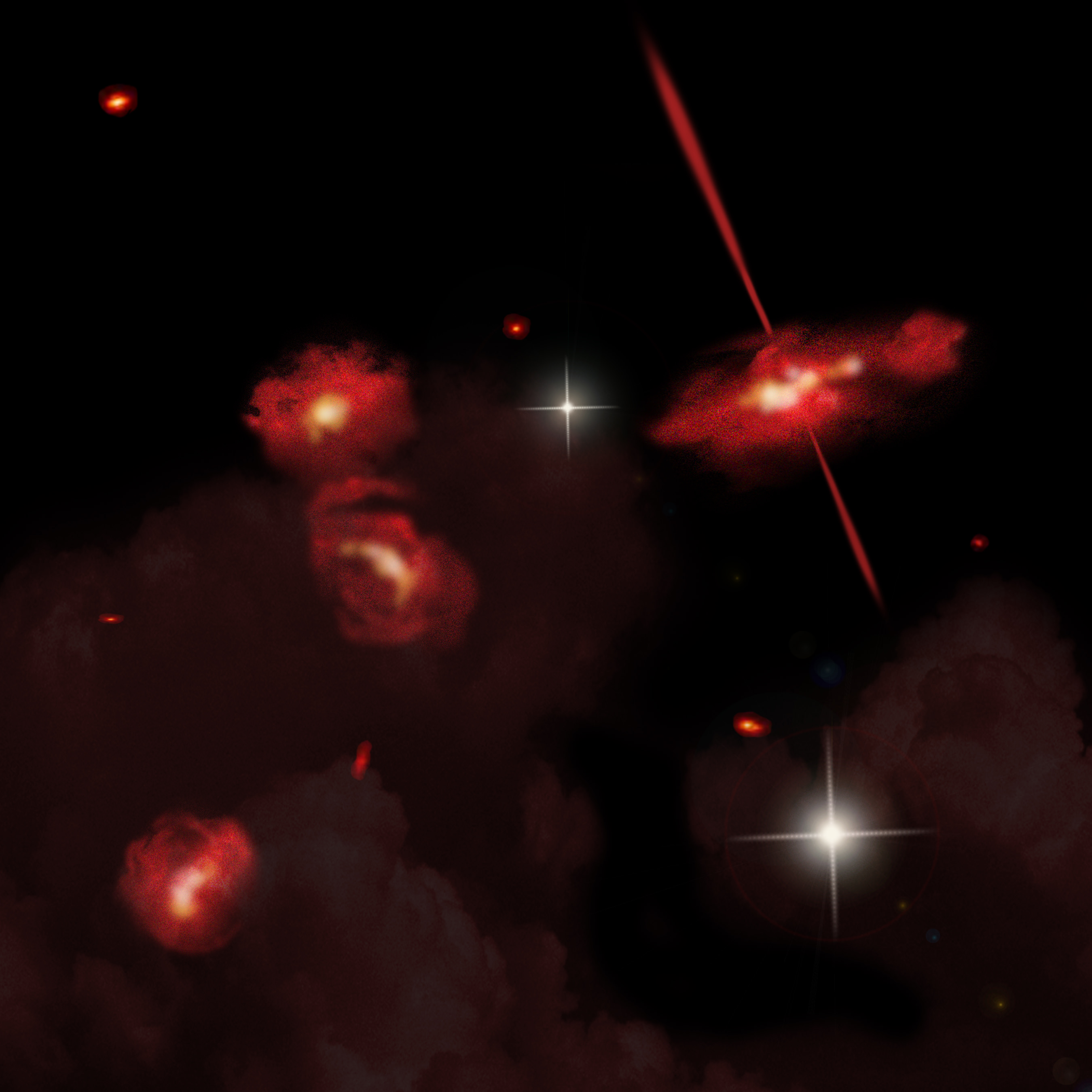

[/caption]Using the partially constructed ALMA observatory, a group of astronomers have found new evidence that helps explain how young, star-forming galaxies end up as ‘red and dead’ elliptical galaxies.

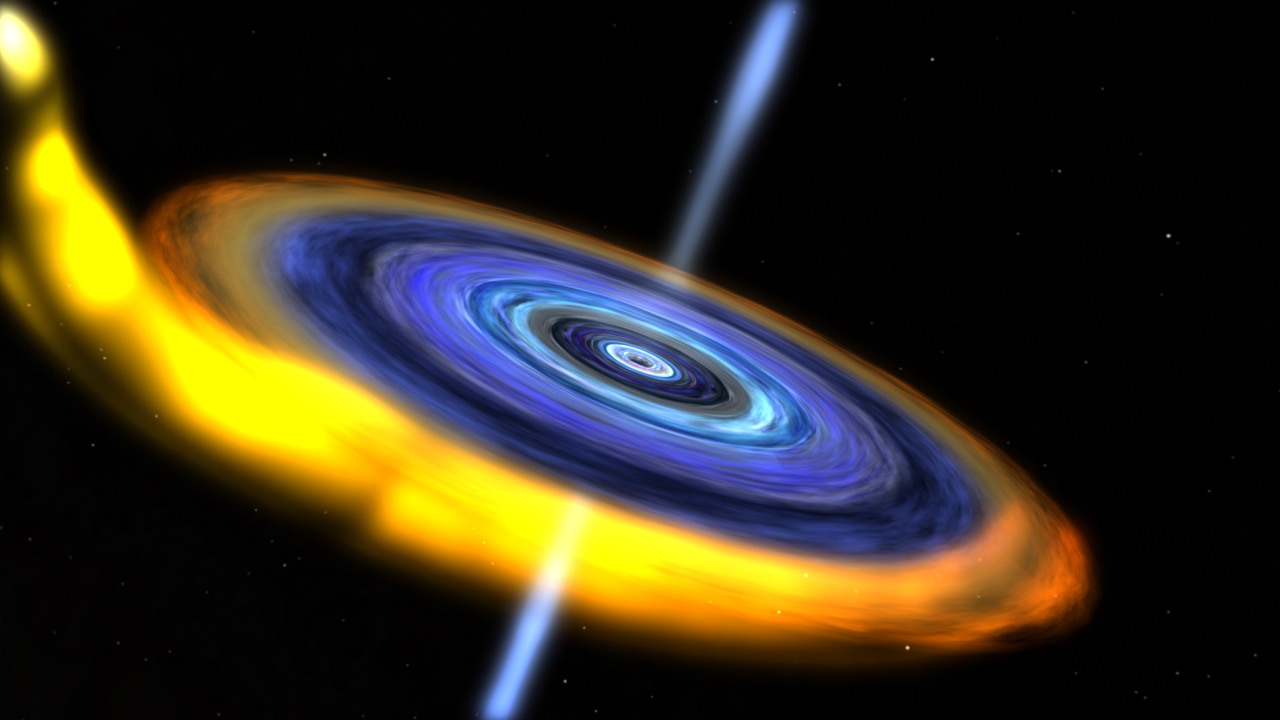

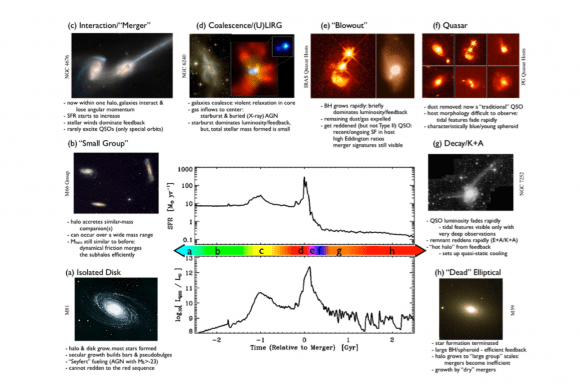

According to current galactic evolution theories, mergers of spiral galaxies are thought to explain why nearby elliptical galaxies have few young stars. Merging galaxies direct gas and dust into starburts, which are regions of rapid star formation, as well as into the central supermassive black hole at the core of the merging galaxies. As matter is piled onto a black hole, powerful jets erupt, and the region becomes a brightly shining quasar. Eventually the powerful jets emanating from the central black hole push away any potentially star-forming gas, which causes the starbursts to cease.

Astronomers have, until recently, been unable to detect enough mergers at the “jet” stage to make a definite link between the outflows and the end of starburst activity. During early science observations in 2011, ALMA became the first telescope to confirm almost two dozen galaxies at the critical, yet brief stage of galaxy evolution.

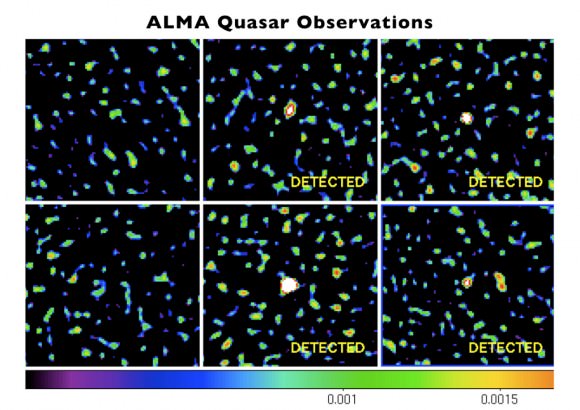

“Despite ALMA’s great sensitiviy to detecting starbursts, we saw nothing, or next to nothing – which is exactly what we hoped it would see,” said Dr. Carol Lonsdale (NRAO). Lonsdale presented the findings at the American Astronomical Society’s meeting in Austin, Texas on behalf of an international team of astronomers.

ALMA was set to look for the signature of dust warmed by star-forming regions. Half of Lonsdale’s two dozen galaxies were not visible in ALMA’s observations, and the other half very dim.

“ALMA’s results reveal to us that there is little-to-no starbursting going on in these young, active galaxies. The galaxy evolution model says this is thanks to their central black holes whose jets are starving them of star-forming gas,” Lonsdale said. “On its first run out of the gate, ALMA confirmed a critical phase in the timeline of galaxy evolution.”

After the star-forming gas is blown away, merging galaxies no longer form new stars. Once the massive, bright, blue, and short-lived stars die out, the redder, longer-lived, lower mass stars begin to dominate the population, leading to a gas-starved galaxy taking on a redder hue. To support the gas-starvation theory, astronomers needed to observe the process at work, specifically in merging galaxies with high power jets where quasars can be found.

Lonsdale added, “The missing phase had to be among quasars that could be seen brightly in infrared and radio wavelengths — mergers young enough to have their cores still swaddled in infrared-bright dust, but old enough that their black holes were well fed and producing jets observable in the radio.”

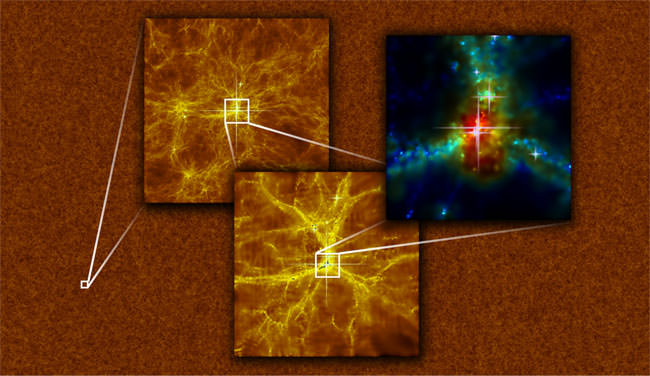

The team’s hunt for the specific type of quasars began with NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) spacecraft. The WISE data consists of millions of objects in its all-sky survey of the Universe. Lonsdale led WISE’s quasar survey team that picked out the brightest, reddest objects this infrared telescope had mapped.

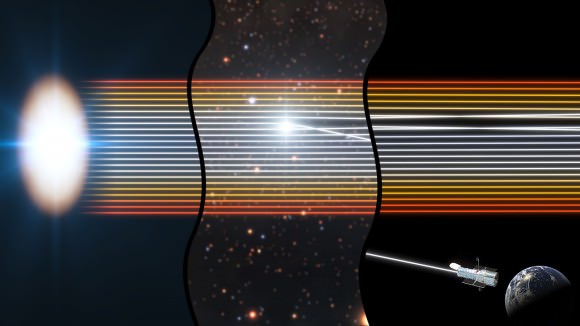

Lonsdale and her team compared the WISE data against the NRAO’s VLA Sky Survey of 1.8 million radio objects. The team then used results common to both sets of data to determine the best targets for their starburst search with ALMA. Since ALMA uses longer infrared wavelengths than WISE, Lonsdale’s team was able to make the distinction between dust warmed by starburst activity and dust heated by material falling onto the central black hole.

There are 26 more WISE quasars for ALMA to survey before Lonsdale and her team publish their results. In the meantime, Lonsdale and her team will observe these galaxies with the newly re-named Karl G. Jansky Very Large Array (VLA).

“ALMA revealed to us this rare stage of galaxy starvation, and now we want to use the VLA to focus on delineating the outflows that robbed these galaxies of their fuel,” Lonsdale said. “Together, the two most sensitive radio telescope arrays in the world will help us truly understand the fate of spiral galaxies like our own Milky Way.”

If you’d like to learn more about the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA), visit: https://almascience.nrao.edu/about-alma/alma-site

Source: NRAO Press Release