[/caption]

Trying to understand the warping of space and time is something like visualizing a scene from Alice in Wonderland where rooms can change sizes and locations. The most-used description of the warping of space-time is how a heavy object deforms a stretched elastic sheet. But in actuality, physicists say this warping is so complicated that they really haven’t been able to understand the details of what goes on. But new conceptual tools that combines theory and computer simulations are providing a better way to for scientists to visualize what takes place when gravity from an object or event changes the fabric of space.

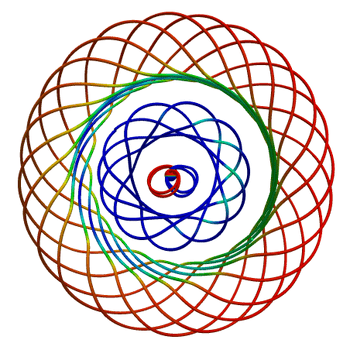

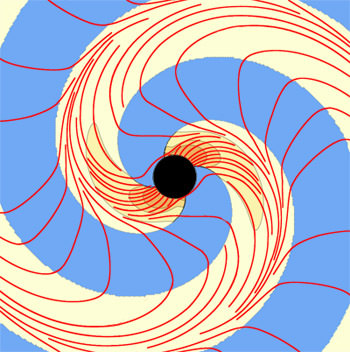

Researchers at Caltech, Cornell University, and the National Institute for Theoretical Physics in South Africa developed conceptual tools that they call tendex lines and vortex lines which represent gravitation waves. The researchers say that tendex and vortex lines describe the gravitational forces caused by warped space-time and are analogous to the electric and magnetic field lines that describe electric and magnetic forces.

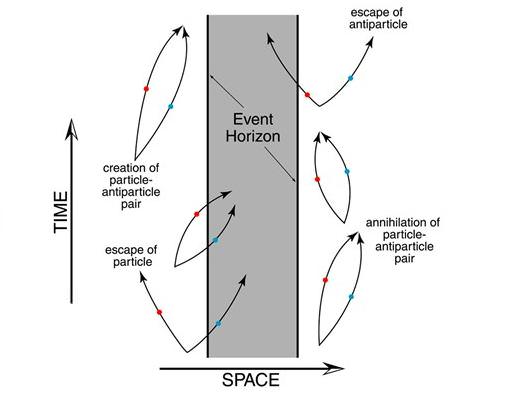

“Tendex lines describe the stretching force that warped space-time exerts on everything it encounters,” said says David Nichols, a Caltech graduate student who came up with the term ‘tendex.’. “Tendex lines sticking out of the Moon raise the tides on the Earth’s oceans, and the stretching force of these lines would rip apart an astronaut who falls into a black hole.”

Vortex lines, on the other hand, describe the twisting of space. So, if an astronaut’s body is aligned with a vortex line, it would get wrung like a wet towel.

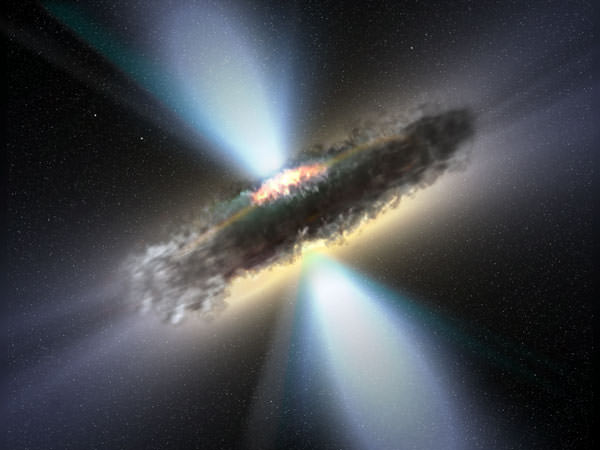

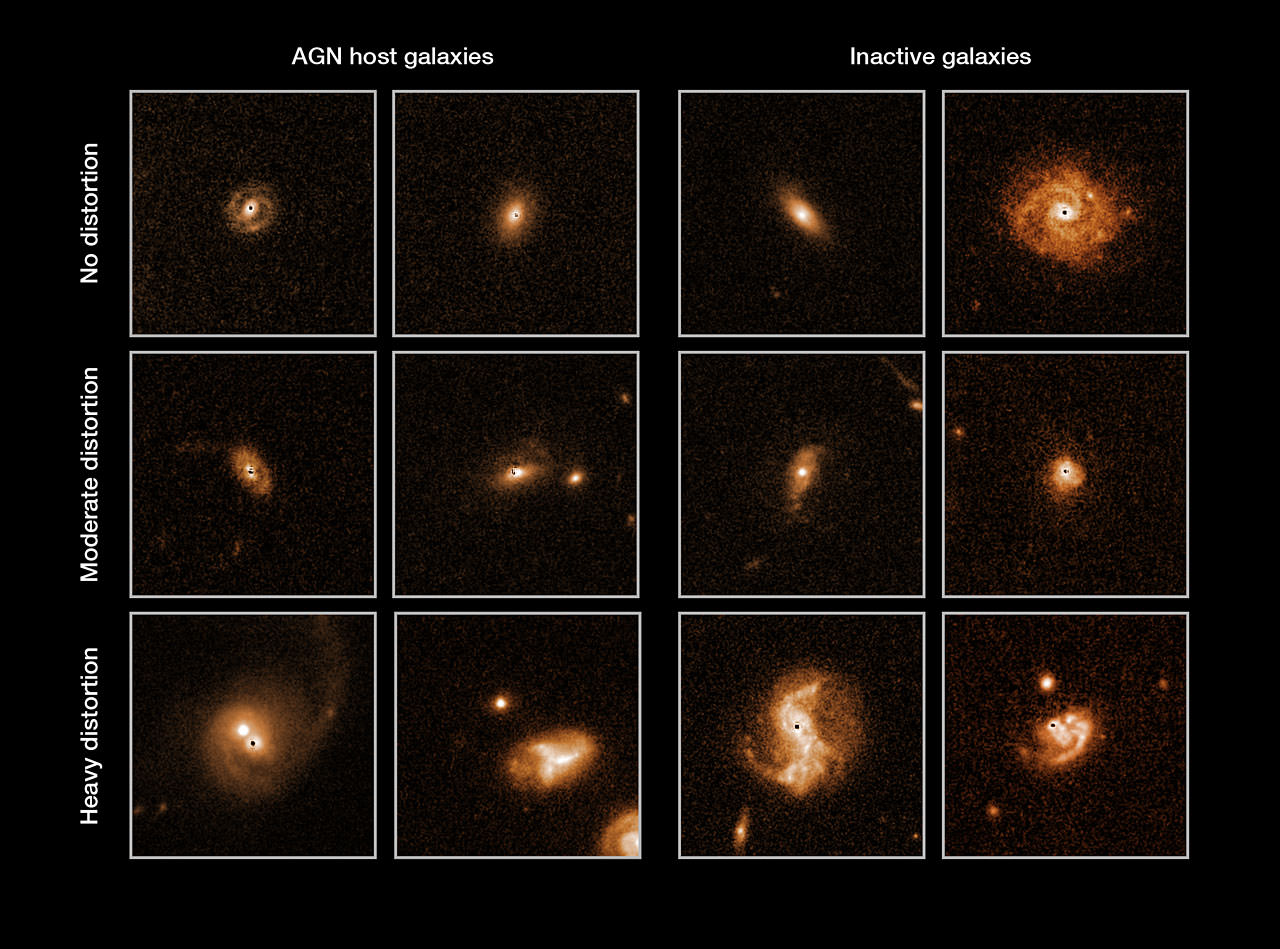

They tried out the tools specifically on computer simulated black hole collisions, and saw that such impacts would produce doughnut-shaped vortex lines that fly away from the merged black hole like smoke rings. The researchers also found that a bundle of vortex lines spiral out of the black hole like water from a rotating sprinkler. Depending on the angles and speeds of the collisions, the vortex and tendex lines — or gravitational waves — would behave differently.

“Though we’ve developed these tools for black-hole collisions, they can be applied wherever space-time is warped,” says Dr. Geoffrey Lovelace, a member of the team from Cornell. “For instance, I expect that people will apply vortex and tendex lines to cosmology, to black holes ripping stars apart, and to the singularities that live inside black holes. They’ll become standard tools throughout general relativity.”

The researchers say the tendex and vortex lines provide a powerful new way to understand the nature of the universe. “Using these tools, we can now make much better sense of the tremendous amount of data that’s produced in our computer simulations,” says Dr. Mark Scheel, a senior researcher at Caltech and leader of the team’s simulation work.

Their paper has been published in the April 11 in the Physical Review Letters.

Source: CalTech